Stories > A Life Worth Living

A Life Worth Living

Singaporean non-profit organisation Impart trains volunteers to provide support to high-risk youths who are facing adversity and mental health issues.

BY RACHEL AJ LEE

uicide is the leading cause of death for those aged between 10 and 29 years in Singapore. In 2020 alone, 452 lives were lost. This statistic was recently highlighted in a report by Samaritans of Singapore, a non-profit organisation that provides confidential emotional support to individuals facing crisis and are harbouring thoughts of suicide.

As mental health becomes a pressing issue in societies, exacerbated by Covid-19 lockdowns and extended periods of social isolation, several organisations have sprung up to respond to the need of the hour.

One such local non-profit initiative, Impart, trains and equips youth volunteers in healthy stress management strategies and peer support. With the belief that suicide can be prevented with collective efforts, the ground-up organisation’s goal is to build a community of young individuals who can care for and journey with each other in dealing with mental health issues.

Launched in 2015, Impart’s target group is at-risk youths between 10 and 24 years of age, who are facing adversities such as peer pressure in school, financial difficulties, domestic violence and homelessness.

NOT A COOKIE-CUTTER MODEL

Joshua Tay, Impart’s co-founder, first met his fellow co-founder, Narash Narasimman, eight years ago at Singapore Boys’ Home – a government-led rehabilitation centre for youths who are in conflict with the law. Both were keen to find a better way to help high-risk youths.

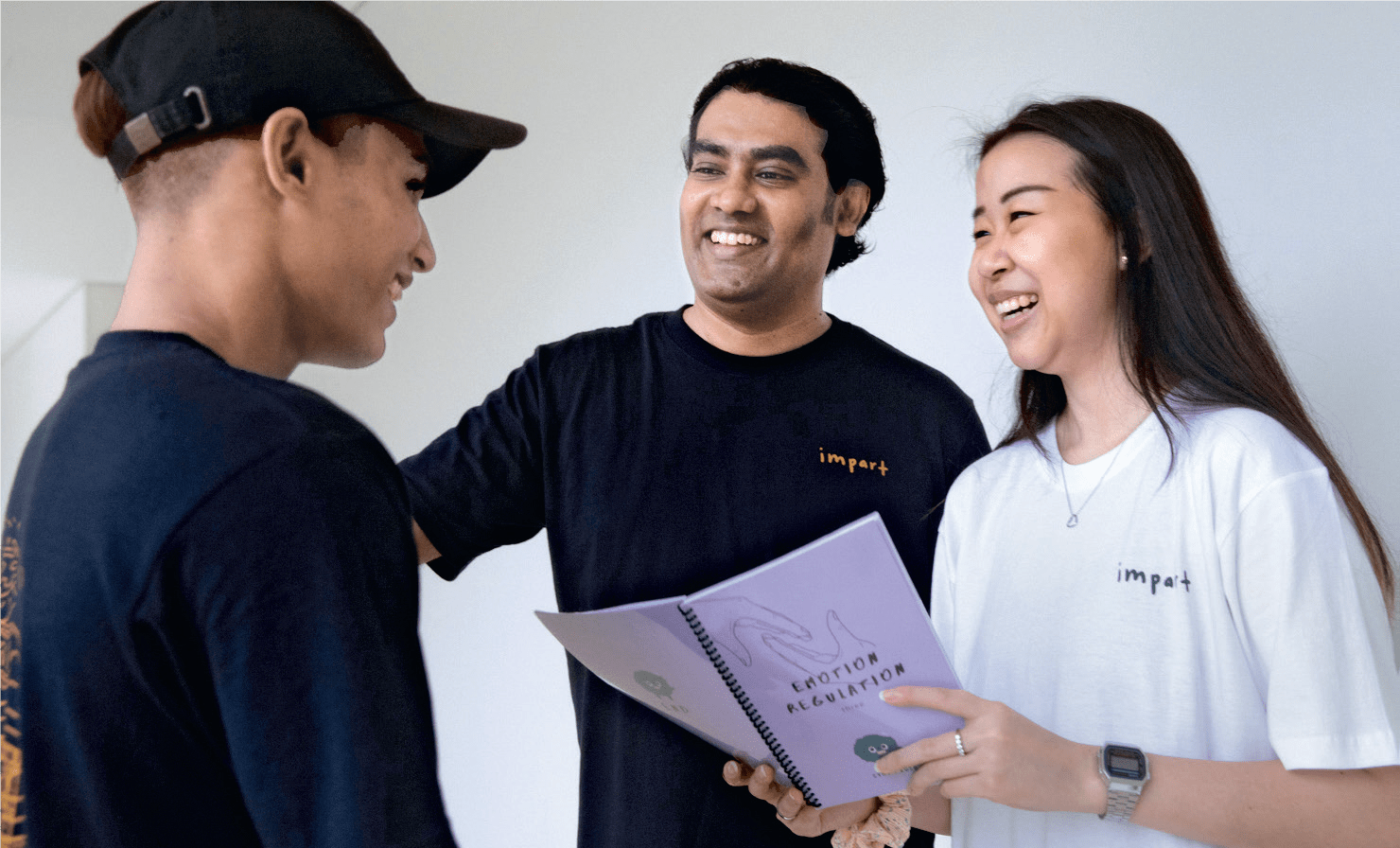

Narash Narasimman (centre), co-founder of Impart, shares that the non-profit’s rigorous training ensures that volunteers are committed.

Tay shares that while he was “impressed” by the resources that the government was pouring into such institutions, he realised that in the existing assessment criteria, individuals had to “be in a bad enough situation to receive help”. Furthermore, these resources “dried up” the moment the youth beneficiaries left the institution.

Although, there were still help programmes available in a group-based setting at a fixed time and location, they did not take into consideration “variability and turbulence”, or for that matter, what youths were experiencing on an individual basis.

“That is how we started to think about how community resources could be gathered and developed for those facing significant adversity,” shares Tay. The duo realised that volunteers or youth advocates were “underutilised”, and could be “scaled up”.

“THINK ABOUT IMPART AS THE PROVIDER OF HEALTHY MODELS OF COMMUNITY RELATIONSHIPS TO THOSE IN NEED. IF YOU ARE INVESTING IN THE COMMUNITY THAT YOU ARE A PART OF, THEN YOU WILL ALWAYS BE FOR THE BETTER. IF COMMUNITIES GROW STRONGER BECAUSE OF YOUR PRESENCE, YOU WILL BENEFIT AS WELL,” SAYS JOSHUA TAY, CO-FOUNDER, IMPART.

“We are not trying to shift resources away from institutions,” stresses Tay. “Think about Impart as the provider of healthy models of community relationships to those in need. If you are investing in the community that you are a part of, then you will always be for the better. If communities grow stronger because of your presence, you will benefit as well,” Tay elaborates.

Impart’s volunteers are also provided with access to mindfulness programmes to ensure that their mental health needs are taken care of before they can help others.

Impart’s operations are currently divided into three pillars: Impart Education, Impart Community and Impart Mental Health Care. Referrals usually come from schools, the Ministry of Social and Family Development, psychologists, institutions and child protection services. The organisation has thus far received and continues to receive a fair amount of support from the government, philanthropists, foundations, private donors and corporations.

Apart from financial concerns, Tay shares that a key challenge was whether people believed and understood how an organisation like Impart could rely heavily on peer-to-peer support, and a volunteerdriven outreach and engagement model.

“In our pilot phases, we leaned on the ensuing organic traction to develop volunteers who shared their experiences with other potential volunteers, professionals referred other professionals, and youths started spreading the word to other friends in need,” Tay shares.

Fortunately, the exposure provided by Our Better World (OBW) – Singapore International Foundation’s digital storytelling platform – also helped to create awareness about the organisation, not to mention encouraging more than 100 volunteers to sign up.

“I think that OBW has helped to raise awareness that this sort of community intervention and services for mental health can actually be provided. While panels and campaigns help raise awareness to a large extent, rarely do people think they can make a direct impact,” Tay points out.

CARING FOR THE VOLUNTEERS

Impart currently has about 350 volunteers, where the majority – about 80 per cent – are university students studying psychology and counselling, while the other 20 per cent are made up of diploma students as well as young working adults. The current ratio is two volunteers to one youth, as this provides better “accessibility” and “quality of care”, Narasimman shares.

When asked how they dealt with volunteer dropouts, Tay states that Impart’s working model is “premised on us being able to engage volunteers”.

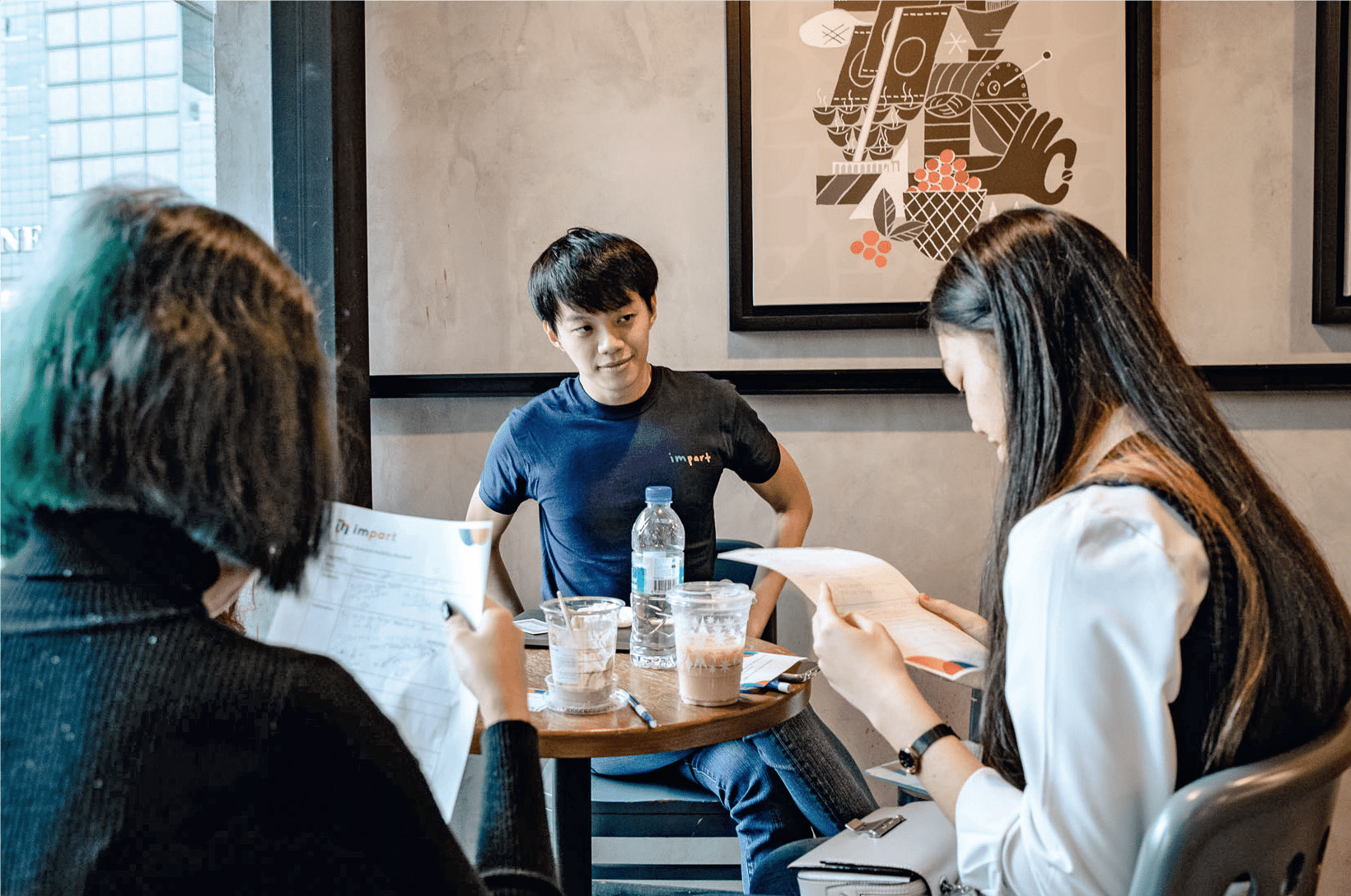

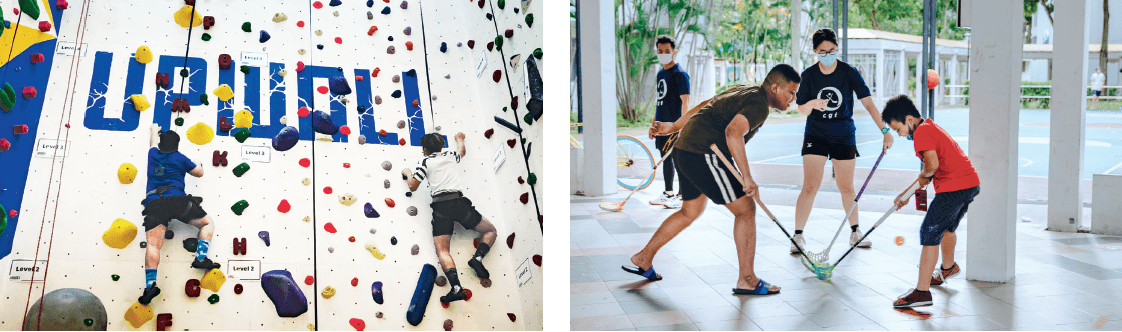

In addition to therapy, at-risk youths are engaged through creative activities so that they can pick up new skills.

Narasimman sheds more light: “Our interview process is not easy. Volunteers also have a probation period of two months where they come in for rigorous weekly training sessions, and are required to pass several tests.” Doing so enables Impart to assess volunteers’ commitment, and ensure that they are completely invested in helping their youth charges.

“We also have another group of volunteers called the Community Care Fellows, who conduct regular check-ins with the entire volunteer pool,” shares Narasimman. Impart has also purchased premium accounts with Headspace – a mindfulness and meditation app – for its volunteers. The organisation supports volunteers by ensuring that the latter are not weighed down by too many cases and by providing subsidised therapy sessions, to help them be in a positive mental state.

Delwyn Leong, 23, an undergraduate computer science student who has been volunteering for a year, says that the work has been “meaningful and fulfilling”, albeit “bumpy”, as he is one of the volunteers without a psychology background.

“I needed to focus more on training workshops, and be more active in seeking advice. Meeting my first youth client was nerve-wracking, but my mentor helped me ease into the programme,” he recalls.

Leong shares that he was motivated to join the non-profit as he was looking for a way to give back to the community, having witnessed first-hand the mental health struggles of a family member.

Impressively, he juggles his studies, a parttime job, as well as volunteering. Through this stint, he has also picked up mindfulness exercises such as grounding and distress tolerance skills, as well as a better understanding of one’s hierarchy of needs.

“WHILE IT WAS INITIALLY DIFFICULT FOR ME TO JUGGLE VOLUNTEERING AND THE INTENSE TRAINING WITH PART-TIME WORK AND FULL-TIME STUDIES, SEEING MY EFFORT PAY OFF HELPS TO OFFSET THE FATIGUE,” SAYS VOLUNTEER SAMANTHA KANG.

Similarly, for Samantha Kang, 23, a psychology undergraduate who has been volunteering for around a year, being a part of Impart has also enabled her to pick up life skills such as being able to handle her own emotions better during and after challenging encounters.

Calling her volunteer stint both “difficult and fulfilling”, Kang first learnt of Impart through its Instagram page, and was keen to pursue a programme called Project Cope. This involved teaching youths coping skills from Dialectical Behavioural Therapy — an evidence-based therapy model that helps people learn and use new skills and strategies to build meaningful lives.

“While it was initially difficult for me to juggle volunteering and the intense training with part-time work and full-time studies, seeing my effort pay off sometimes helps to offset the fatigue that comes with juggling many commitments,” she surmises.

A HIDDEN PANDEMIC

Mental health has emerged as a hidden pandemic from the merciless shadows of a still ongoing pandemic. While more awareness has opened conversations within society, the road ahead is full of challenges.

“It is a good start that more people are talking about it, but there is a lot more to be done. Many people talk about self-care, but practical steps need to be taken on a dayto- day basis,” says Narasimman, adding that therapy needs to be de-stigmatised — most individuals do not have a basic understanding of what therapy is, while others are completely resistant to it.

“In the education system and society we grew up in, we were not actively taught to recognise signs of distress – it was something we slowly figured out ourselves,” says Leong. He adds that an “unexpected outcome” of being a youth advocate has actually helped him become more conscious of his own mental health and embrace coping mechanisms, such as scheduling solitary time and going on long walks.

“I have also learnt to better empathise with others, especially youths, after seeing them through different lenses,” Leong says. “For example, if a youth seems anxious, I now know that I have to look at their previous experiences, traumas or the environment in which they grew up. All of these factors could contribute to them feeling insecure,” he shares.

For Kang, she has learnt how to connect with youths from vastly different backgrounds and experiences, saying that it is a humbling experience. She has also learnt more about having “healthy boundaries in relationships”, something she did not realise was important before joining Impart. “In Asian societies, harmonious relationships are important and we were taught at a young age that rejecting people is impolite. However, when these individuals grow up, they find it difficult to say no and establish boundaries both in terms of relationships with loved ones and at work,” she explains.

“Sometimes, it is hard to tell your boss that you do not want to reply to emails past a certain time. Or you need time away from your friends for self-care. But not being able to establish boundaries will eventually lead to anger, resentment and burnout. It is important that we break the cycle of avoidance coping that has been passed through generations,” Kang concludes.

COMMUNITY BEFRIENDERS

Community organisations are springing up around the world with a focus on mental health and suicide prevention among individuals.

ORYGEN, AUSTRALIA provides specialist mental health services for young people aged 15 to 25 years who reside in the western and north-western regions of metropolitan Melbourne.

ROOTS OF HOPE, CANADA is a community-led project under the Mental Health Commission of Canada that builds upon community expertise to implement suicide prevention interventions tailored to the local context.

KHOSISH, NEPAL has been working to promote mental health at the grassroots and policy level since 2008. The non-profit offers a 24-hour helpline, and manages shelters and other communitybased projects in support of psychosocial well-being.

STRONGMINDS, UGANDA & ZAMBIA is a charity that provides free therapy and peer-to-peer support to low-income women and adolescents living with depression.

KIOWA TEEN SUICIDE PREVENTION PROGRAM (KTSP), USA offers suicide prevention training, bullying and depression awareness presentations. It also provides lessons in life skills at the individual and community levels.

Scan the QR code or visit

https://www.ourbetterworld.org/

series/mental-health/story/-

impart-ing-a-life-worth-living

to find out more.