It was January 1819. He watched from a ship. Then he ventured upriver with a musket-bearing soldier to meet the local chief and negotiate a treaty that would forever change the sleepy village. Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, ambitious, educated and creative, had a prescient vision for the isle of Singapore.

It was January 1819. He watched from a ship. Then he ventured upriver with a musket-bearing soldier to meet the local chief and negotiate a treaty that would forever change the sleepy village. Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, ambitious, educated and creative, had a prescient vision for the isle of Singapore.

By Michele Koh Morollo

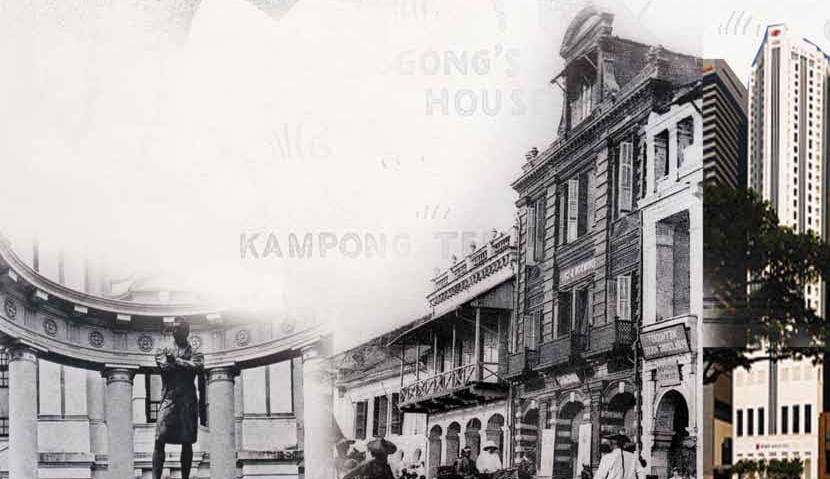

Raffles Place dominates the south bank of the Singapore River. Its imposing business towers, a glittering part of Singapore’s skyline, carry an added sparkle from the billions of dollars that pulse through these skyscrapers every working day as the nation’s financial and commercial heart. Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, saw this possibility in the sleepy fishing settlement almost 200 years ago, but it was unlikely that even he could have imagined what lay ahead.

Raffles first set foot on Singapore on 29 January 1819, after spending a day anchored off St John’s Island in a flotilla of nine ships. He was already a seasoned hand in Asia, having been posted to the Far East in 1804 as Assistant Secretary to the Governor of Penang. He had shown himself ambitious as, after getting employed by the East India Company in London at 14, he taught himself the natural sciences, history and several languages. Wit complemented his ability, which gained him favour with his superiors and postings in Asia.

Outdoing the Dutch

By the time Raffles laid eyes on Singapore, he was well aware of Dutch dominion over trade in the Far East. He had been on the Indiana surveying the islands south of the Malay peninsula for almost two months at the then Governor-General of India Lord Hasting’s behest. His mission was to find a port to strengthen Britain’s position for trade. He saw it in Singapore — a backwater location blessed by geography and favoured by the winds for vital commerce. Raffles had pipped the Dutch to a jewel.

But first he had to negotiate for Britain’s right to trade from it. Before stepping ashore on sparsely populated Singapore, Raffles entertained some bold and curious locals aboard his ship and learnt that Temenggong (village chief) Abdul Rahman, a vassal of Sultan Hussein of Johor, was in charge of the island. He arranged to see him the next day with Major-General William Farquhar, another East India Company employee.

Wah Hakim, a 15-year-old islander then, chronicled Raffles’ arrival with Farquhar at the Temenggong’s home noting the two men were accompanied by a musket-bearing sepoy (Indian soldier) and were feted with local fruit like rambutans as a provisional treaty was discussed. When it was agreed upon, the British flag was hoisted in Singapore.

Setting the Stage

The impetus that has driven business since that day was free trade: “The Port of Singapore is a free port, and the trade thereof is open to ships and vessels of every nation…equally and alike to all.” This brilliant move attracted ships to the port. Ten weeks after Raffles’ arrival, the scattering of local Malay sail boats was joined by two large merchant vessels and a hundred smaller trading ships. In two years, 2,889 vessels had plied the port and by 1825, Singapore was handling trade worth an estimated £2,610,440. By the 1830s, Singapore overtook Batavia (Jakarta) as centre of the region’s trade.

Raffles could see Singapore’s potential as a “great commercial emporium” with a bustling business hub. He initiated a Town Plan in 1822, where a quiet stretch of green with a hill and a few buildings was marked as Commercial Square. It was renamed Raffles Place in 1858 as merchant offices, banks, godowns and jetties sprang up. Business grew and boomed, making Raffles Place what it is today, a district where the spirit of commerce thrives and drives the island nation — a living testimony of Raffles’ vision. Free trade carried the country’s GDP from S$2,156.5 million in 1960 to S$326,832.4 million in 2011.

The Raffles’ Letters: On display at the Singapore National Library till February 2013 is a rare collection of 20 letters written by Sir Stamford Raffles, which give insight into the founding of Singapore, and his vision and struggles in pursuing it. In one letter, Raffles writes about his difficulty in securing enough troops to maintain a British presence in Singapore. In another, he hopes for Singapore’s true value to one day be “fully and justly appreciated by all parties”.

Today, more than 120,000 ships call at Singapore annually. At any one time there are about 1,000 vessels in the nation’s waters. Singapore remains one of the busiest ports in the world.

Raffles: Life and Times

Sir Stamford Raffles appeared destined for a life of adventure across the seas. He was born in the Caribbean Sea on board the merchant ship Ann near Jamaica on July 6, 1781, the son of its captain, Benjamin Raffles.

At 23, he was posted to Penang where he fell in love and married the widow Olivia Marianne Fancourt. A colourful stint in the Far East saw him made Lieutenant Governor of Java after a sharp and successful military campaign, his honour questioned by accusations of mismanaging colony funds, and heartbroken over the death of his wife. He returned to England under a shadow. There his fortunes turned again. He wrote a book, History of Java, was knighted by the Prince Regent King George IV In 1817, married his second wife Sophia, and was appointed Governor-General of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu), Sumatra. He sailed back to Indonesia with his new wife for his new post — which led to the Empire’s claim of Singapore.

The official date of Singapore’s founding is 6 February 1819, the day the Singapore Treaty was officially signed between Raffles, Sultan Hussein of Johor and the Temenggong of Singapore.

Raffles last visited Singapore in 1822 on his way back to England from Bencoolen. Thrilled with the colony’s exponential progress but dismayed with Farquhar’s administration of it, he wound up staying a year. And what a year it was.

He drafted Singapore’s first constitution and laws, and had a hand in setting up Singapore’s education system. He founded the country’s first official school in 1823, then known as Singapore Institution (Raffles Institution today). He was involved in choosing the site, as well as launching a subscription to build the school. He so believed in it as the school to groom leaders for the new colony that he made a personal donation of $2,000 towards it. The motto of the school, Auspicium Melioris Aevi — the hope for a better age — appears to have helped it live up to Raffles’ hopes. Some of its students include Singapore’s former Prime Ministers Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Chok Tong.

Meanwhile, Raffles remained enthralled by the biodiversity he discovered in Asia. The Botanical and Experimental Garden on Government Hill in Fort Canning was his idea. Established in 1822, it is today the 32ha Singapore Botanic Gardens, listed by some international organisations as one of the most beautiful public gardens in the world.

Raffles’ personal assistant and Malay tutor, Munshi Abdullah, recalled helping him pack some 1,000 animal and plant specimens, notes, papers and drawings for what would be his final voyage home to England in 1824. He was leaving with a heavy heart — five of his six children had died young, mainly from tropical diseases.

Tragically, a fire onboard the ship destroyed a large part of this collection. Raffles’ passion for the natural sciences saw him describing some 34 species of birds and 13 mammals, and these continue to remind us of his contributions. A number of animals and plants have also been named in his honour.

Undaunted by all his personal losses, Raffles founded the now famous Zoological Society of London. Elected its first president in 1826, he assisted in opening the London Zoo even as his health deteriorated. The man considered largely responsible for creating Britain’s empire in the Far East, with Singapore as a jewel, died a day before his 45th birthday, his life cut short but his vision living on.