Stories > A Taste Of Things To Come

A Taste Of Things To Come

t is indeed a truth when we often hear that “the food in Singapore is amazing”. With all its multicultural and multicoloured textures, tastes, layers and combinations, Singaporean food is truly sublime. It represents the diners’ tastes, and also — perhaps more than any place in the world — it embodies who we are as a people; a polyglot, multiethnic society united by our love for food.

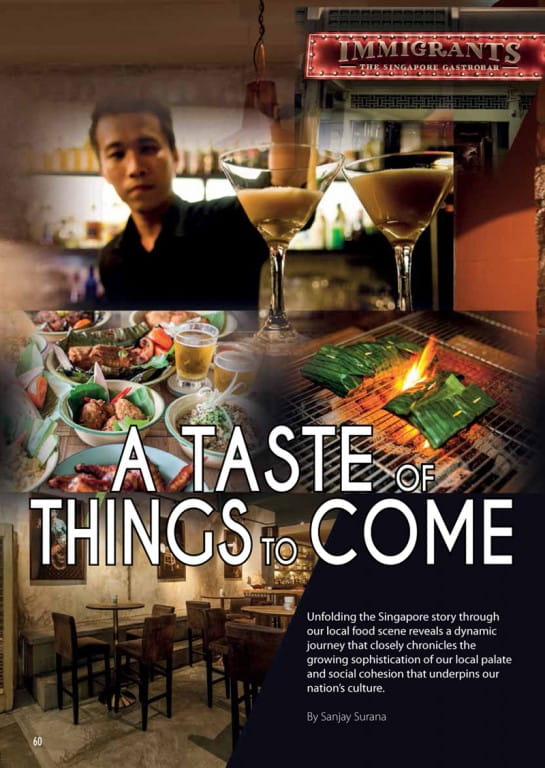

“There are two schools of Singapore’s cuisine — hawker food and heritage food,” says Damian D’Silva, owner and chef at Immigrants, a gastrobar on Joo Chiat Road that’s been written about in the New York Times.

“Hawker food was introduced more than a century ago, catering to the labourers as a cheap alternative to the food available in restaurants. It consisted of food from the various ethnic backgrounds, mostly Chinese, Malays, and Indians,” he adds.

Damian D’Silva brings out the strengths of heritage fare.

D’Silva explains that heritage food is more complex, and offers a cuisine that evolved in the 1600s from different communities. These include the Europeans that colonised Southeast Asia, starting with the Portuguese followed by the Dutch and ending with the British. In fact, his restaurant offers just that, with a fare comprising the dishes of the major ethnicities in Singapore.

Seetoh says that food to Singaporeans is both comfort and culture. “Our street food is a show about us, who we are, and what each race and creed has contributed to the country’s popular culinary landscape today. It spells Singapore in so many ways. There are no boundaries now, everyone enjoys each other’s food without question, and the only fear is that it’s not done to expectations.”

“Our food is very different from our neighbours’, mainly because of the mixed heritages that have evolved through intermarriage. It’s hard to define specifically, but that’s what makes Singapore special.”

— Damian D’Silva, owner and chef, Immigrants Gastrobar

It’s been argued that Sir Stamford Raffles created the conditions for Singaporean food as we know it today. When he landed here on January 29, 1819, to set up a trading post for the East India Company, he encountered a largely undeveloped, lightly populated island. Within days he had formally established Singapore as a British settlement, and soon drew up housing plans and rules for the harbour, built carriage roads and cantonments for soldiers. His establishment of the settlement, its basic governance, and foundation for trade attracted immigrants from India, other parts of British Malaya, Europe and Armenia. The Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese, Hokkien, and Teochew communities also arrived in search of work and fortune. Peranakans moved from Malacca to Singapore, while some Chinese here, with Balinese, Batak, and Bugis wives, started a new bloodline of Peranakans. This cultural mingling, the likes of which Singapore had not seen on such a grand scale, provided the building blocks for today’s multicultural society.

Describing the hawker-food scene, KF Seetoh, who defines himself as a culinary anthropologist, calls Singapore “a pure food democracy created by desperation, where migrants once had to hawk their heritage flavours on the streets to make ends meet”. It’s the melding, not the melting pot that makes it unique, he adds. For instance, the Chinese have adapted well to Indian curries and created iconic curry rice. The Malays have Chinese-style cze cha (stir fry) cuisines too.

Dr Leslie Tay, a full-time physician who runs the hugely popular ieatishootipost blog in his scant spare time, pinpoints our location for the richness of the food. He says: “We are a transshipment port, at the crossroads of east and west, south and north. Lots of ships come and we like to take a bit off each ship so to speak. A hawker centre is a microcosm of Singaporean society.”

Dr Leslie Tay indulges in the cross-cultural fare at a hawker centre.

Using mee rebus – a popular Malay noodle dish with a thick sauce — as an example, Dr. Tay says that the noodles are from China, but the other ingredients are Malay and now it’s become a Singaporean food.

Singapore is sometimes unfairly viewed as a society that is lacking culture; as being sterile, but our food scene says otherwise. In addition to the cornucopia of prodigious homegrown concoctions, we have esteemed eateries serving different global cuisines. Asia’s Top 50 Restaurants 2014, lauded haute establishments like the nouvelle French boîte André, the modern-Japanese Waku Ghin, the eclectic Iggy’s, the experimental Tippling Club, and the classic Imperial Treasure Super Peking Duck. This variety at the top-end hints at the range here.

The central role that food plays in society isn’t lost on marketers and promoters either. In a recent photo competition called Stories of our City, held by Canon, the text reads: “Food. Nature. People. The three elements that shape the quint essential life and landscape of Singapore.”

The Singapore Tourism Board hosts a Food Festival every July, and the world’s first-ever Street Food Congress took place here in 2013. And, because of the inferred appeal of food here, Singapore mei fun (a Chinese dish made of thin noodles) or Singapore-style noodles, is a staple in restaurants from New York’s Chinatown to Northbridge in Perth. Ironically, it is technically not a Singaporean dish but one concocted by restaurants overseas.

“Our food is very different from our neighbours’, mainly because of the mixed heritages that have evolved through intermarriage. It’s hard to define specifically, but that’s what makes Singapore special,” declares D’Silva.

This rich tapestry of immigrants has clearly shaped the food that over time has become so familiar, so comforting, so Singaporean.

There are dishes like the pork-rib soup bak kut teh, Hanainese chicken rice, nasi goreng (Malay-style fried rice), Nyonya laksa (Malay curry dish with noodles, fish cakes and tofu) and murtabak (Indian pancakes stuffed with meat). The crossing of cultures, ingredients, and techniques leads a Chinese chef to use tamarind in his dishes, or an Indian cook to fry noodles. And the city’s strategic location on world shipping and air routes means importation of food is a logistical cinch.

“Singaporeans are well-travelled, they bring things home that they bought overseas,” notes Tay. “Some businessmen like to bring chefs back, others import stuff. Today, we have some of the best, freshest Japanese and Italian ingredients available here.”

“I consider it my personal mission to write about Singaporean foods and make them sexy for the younger generation, to try to explain scientifically how to cook a dish and how to make that dish so that it tastes good.”

— Dr Leslie Tay, food blogger

With that greater access to ingredients has come a surge in restaurants serving international cuisines. “We are a melting pot of cultures and able to adapt to concepts efficiently, thus drawing many top chefs from all over the world, increasing our standard and quality of food,” asserts Janice Wong, innovative pastry chef and owner of Holland Village’s 2am:dessertbar. Wong has a balanced perspective; her menu lists Western and Eastern dishes, including the Shades of Green dessert made with pandan (screw-pine leaf), gula melaka (palm sugar) custard and pistachios.

The highest-profile beachhead in the international food scene occurred after the opening of Marina Bay Sands in 2010, with celebrity chefs like Wolfgang Puck, Daniel Boulud, Mario Batali, Tetsuya Wakuda soon following. “Lots of local and international visitors seek a range of dining experiences and this new star-studded set up adds to the credible variety here,” adds Seetoh.

Indeed, Singapore’s shifting dining scene is a far cry from a decade ago. “The current interest in foreign food began developing in the 1990s, and in the last decade has gone through the roof,” says Dr Tay who believes this is a natural cycle. “Flavours and tastes are never static, and these days, as more northern Chinese migrate to Singapore, you see dishes like xiao long bao more commonly found at hawker centres. Ten years ago you couldn’t find it here, now it’s now almost considered local. This shows how the food has evolved, and how the people accept it.”

“We are a melting pot of cultures and able to adapt to concepts efficiently, thus drawing many top chefs from all over the world, increasing our standard and quality of food.”

— Janice Wong, Owner, 2am:dessertbar

D’Silva does fret about the creeping change in tastes. “Unfortunately, our heritage is slowly dissolving, even without the Western influence in our diet. We have become affluent and many who are educated abroad are more familiar with European cuisine than their own heritage. Fast food obviously is partly to blame. We don’t have the opportunity nor the time to prepare food of our forefathers, and many heritage dishes and recipes were buried together with their masters.

“If a quick survey were done to choose a breakfast meal for kids ranging from six to 10 years old, and only two choices were offered, Western fast food or chwee kueh, I can bet my bottom dollar that eight out of 10 children would opt for Western fast food. To think of what will become of Singaporean food in the next decade is a scary thought.”

There are those, however, who are on a quest to ensure that our rich food history doesn’t disappear. Chef Shen Tan, formerly of Wok and Barrel on Duxton Hill, just opened Ujong@Raffles, serving updated Singaporean favourites like nasi lemak beef rendang and chicken rice. Shutters, a woodfloored boîte at Sentosa’s Amara Sanctuary Resort, cooks Singaporean classics using contemporary culinary techniques.

Contributing to the continuing chapters of Singapore cuisine, Dr Tay reflects: “I wrote the book The End of Char Kway Teow because I thought a lot of Singaporean stories are lost. I tried to trace the history of stalls and food. I consider it my personal mission to write about Singaporean foods and make them sexy for the younger generation, to try to explain scientifically how to cook a dish and how to make that dish so that it tastes good.”

D’Silva, despite his concerns, feels a sense of cultural duty. “In the past 20 years, I have endeavoured to cook and teach about Singapore heritage food, comprising Chinese, Malay, Indian, Peranakan, and Eurasian cuisines. We need to continue to preserve a cuisine that took almost 150 years to perfect, it would be sacrilegious to ignore our ancestors’ efforts and time, sacrifices that defined Singaporean cuisine.”