Stories > A view to a change

A view to a change

Using the camera lens to interpret their views of the world, trailblazing photographers use technology for social reform.

By Swapna Mitter

hey roam far and wide for that perfect shot. They come from diverse backgrounds and focus their lenses on different subjects. They are fuelled by the same passion and zeal — to highlight the trials and tribulations of the less fortunate and do all they can through their photography skills to help. Whether it’s raising awareness, money or by imparting their skills to them, they seek to make an impact on the lives of those they capture in their viewfinders.

Blind Faith

Bob Lee

Affable and unassuming, Bob Lee’s life revolves around photography. Lee has worked as a photographer with SPH publications, taught at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA), Ngee Ann Polytechnic and Egg Story Digital Arts School, published several books, has held exhibitions and also worked on humanitarian projects. Now he teaches at Pathlight, one of Singapore’s foremost autism-focused schools, where Lee’s seven-year-old son is also a student.

“Every single day is packed with activities, with photography as the pivotal focus. It is my only hobby and my occupation too; I teach and take photographs instead of watching TV,” he says with a smile.

In 2003, Lee undertook a project called ‘Have a Little Faith’, depicting the daily lives of the Jewish and Sikh communities in Singapore, which was published as a book by the same name in 2005. Another book, One Room Flat — focusing on the hardships faced by predominantly elderly dwellers — was published the same year. In between publishing other books (Ah Bob Baba Zhouji, Curiocity, Onstage Offstage), winning awards (the most prominent being the top honour in ‘Behind the Scenes’ category at the ClickArt: World Photojournalists Meet in 2003, where he beat 200 others from 32 countries) and teaching students, Lee has never failed to use his skills to help the needy.

Whether helping an orphanage in Philippines, making photographic memorabilia for the old and dying, or working with autistic children, he has always showed up with his camera. But one project that ranks high in terms of uniqueness and challenge was one for which he agreed to teach a group of visually impaired persons in 2012.

“Dialogue in the Dark is a centre for the visually impaired at Ngee Ann Polytechnic. When they approached me to teach photography to those working there, I had no idea how to go about it,” recalls Lee. “Then I did some research and found out that someone in the US has done similar work and there’s even a book on it,” referring to Seeing Beyond Sight: Photographs by Blind Teenagers by Tony Deifell.

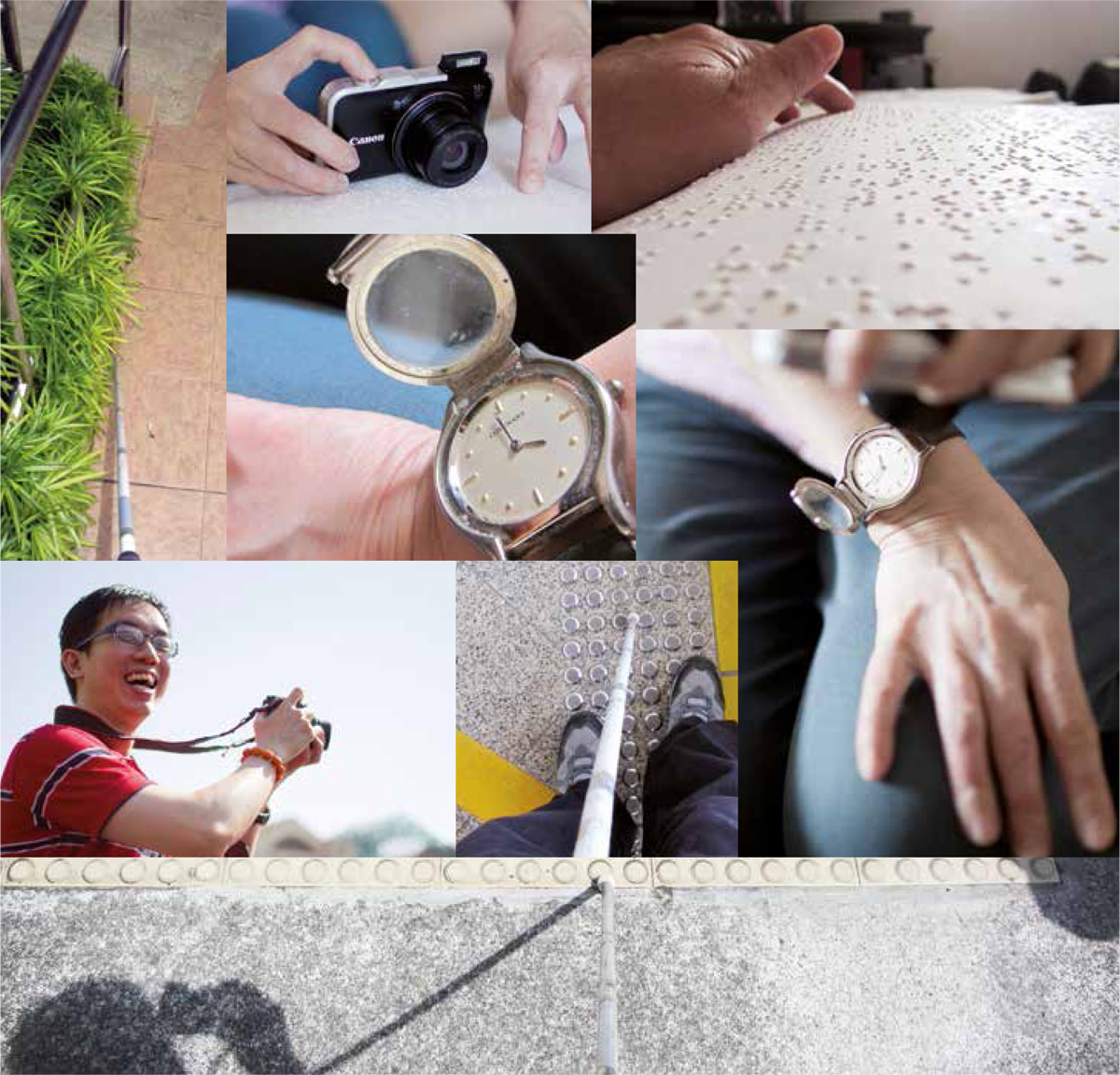

Canon chipped in by donating six good cameras for Lee’s five students and himself. “I blindfolded myself and started playing with the camera before teaching my students. I was also nervous about using words like ‘see’ and ‘look’. But soon I began to relax and spent the first week teaching them how to hold the camera, turn the knob, change batteries and so on.”

Bob Lee prepares his lesson materials by putting on the mantle of a blind person, to better develop his teaching syllabus.

He also took his students outside the school with the help of interns who guided them along since they were holding cameras instead of walking canes. “All of them took their own pictures and created their own angles – they have an innate sense of space and surroundings,” explains Lee.

The rest of the group was given two weeks to take their own photos. During the fifth and final week, he spent one-on-one time with each of them; even going to their homes and helping them with their pictures. The workshop culminated in an exhibition held in August that year. “I encouraged them to speak at the event and managed to get media coverage, including a spot on the radio,” says Lee.

“I blindfolded myself and started playing with the camera before teaching my students. I was also nervous about using words like ‘see’ and ‘look.’

— Bob Lee, who taught blind students to take photographs

To be able to take photographs, exhibit them and explain their journeys during the photography sessions was a unique and thrilling experience for these students.

“I am a positive person, and I, too, have learned from all the people I have worked with,” concludes the downto- earth man with a disarming smile. “Don’t take life or time for granted, when you think of something, just do it.”

The View of Hardship

Sim Chi Yin

Spirited and passionate, Sim Chi Yin has a degree in history and another one in history of international relations from the London School of Economics. She quotes liberally from Albert Camus’ The Outsider, which she read at 18. Based in Beijing for the past six years, the former writer-photographer at The Straits Times and The New Paper is now accredited to The New York Times.

“I could be shooting out in the desert for TIME magazine at the start of a week, then photographing the rich and posh in Shanghai for a book cover, chasing pollution in an industrial city for The New Yorker the following week, and then by the next weekend, I’m deep in the mountains, in the villages with poor, silicosis-stricken miners, for a personal project,” says Sim.

She has always had an interest in social issues. “I was naturally inclined to tell stories of those who can’t necessarily tell their own,” she explains. Early in her career, she shot a story on the last samsui women in Singapore — tough women who migrated from Samsui in southern China around the 1930s to work as construction workers. “The images were exhibited in an unusual way: as posters at bus stops all over Singapore.”

In Beijing, she undertook a 2012 project on Chinese migrant workers unkindly known as the ‘rat tribe’ because they live in basements. Coming from various parts of China – typically smaller towns and villages – they could only afford to live in bomb shelters and basements.

“I hoped to convey through the pictures — which depict fashionable and resilient migrants with carefully decorated rooms — that though they are dubbed ‘rats’, they are just like those living above ground: spunky, hardworking, and upwardly-mobile,” says Sim. Publications from across the world bought and printed these photographs and within China too, one publication, a news website and the Financial Times’s website featured the project.

Lately, though, it’s Sim’s personal project that’s keeping her busy. For two years, she’s been working to highlight the plight of Chinese gold miners. “They are suffering and dying from China’s leading occupational disease: silicosis. They worked in illegal mines with little or no protection from the silica-filled dust when they blasted rock for gold, and are now paying with their lives; waiting in remote, mountainous villages to suffocate to death as their lungs turn into rock,” she says.

“I was naturally inclined to tell stories of those who can’t necessarily tell their own.”

— Sim Chi Yin, award-winning photographer who is championing the plight of coal mine workers of China

Sim Chi Yin (right) champions the plight of coal miners who worked in illegal mines with little or no protection from the silica-filled dust.

There are as many as six million such miners sick with silicosis — that’s almost the whole of Singapore’s population — and the vast majority of them have no contracts or insurance. They now have a very hard time getting good medical care and legal help. With a lot of material in hand, Sim wants to use technology and social media to draw attention to the issue. “This project, save for a small travel grant from the Pulitzer Centre in the US, has been self-funded. How much we do with the campaign and technology also in part depends on how we fund the rest of the project.”

Her passion and grit are getting recognition. She is proud to have been one of the 10 finalists for the W Eugene Smith Grant for Humanistic Photography in 2013, showing her work on the gold miners’ project. “It’s a prize that recognises photographers for a specific focus on social justice issues and a humanistic approach. The winner Robin Hammond has done amazing work on mental health in Africa. To be a finalist is an honour,” says Sim.

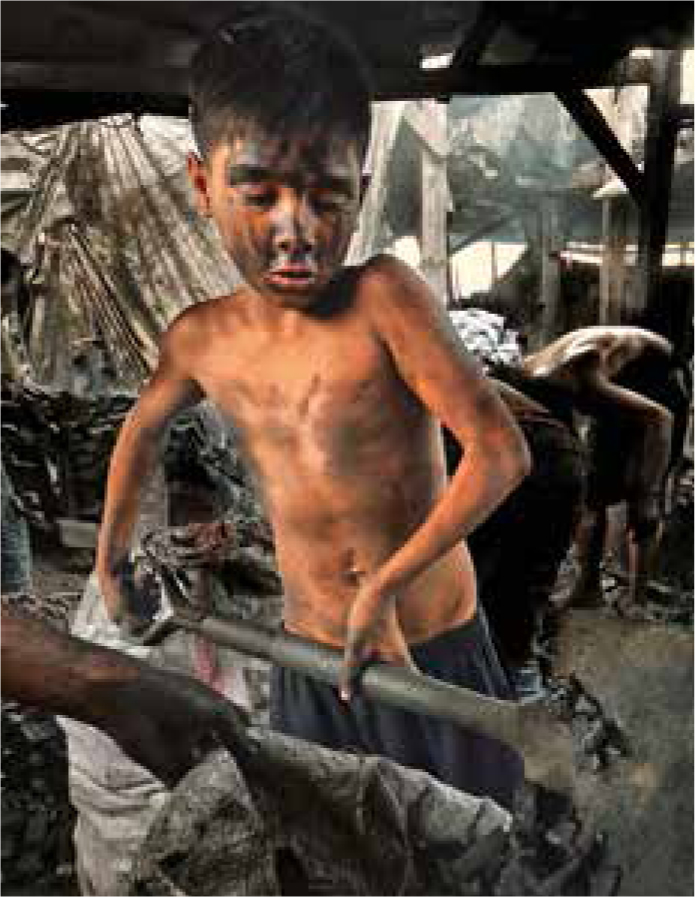

Thomas Tham believes in respecting the rights of the children who are often photographed because of the adverse conditions in which they live or work.

It’s About the Children

Thomas Tham

Thomas Tham strongly believes that a good honest picture is worth a thousand words. “A complex idea can be conveyed with just a single still image, often captured in seconds. It also aptly characterises one of the main goals of visualisation, namely making it possible to absorb large amounts of data quickly,” he explains.

The Malaysia-born lensman has studied in Singapore and UK, and spent many years working for voluntary welfare and social organisations. “I spent four years as a social worker/case manager with Care Corner Family Service Centre, and six years with Home Nursing Foundation as an Information Technology manager,” he says.

Photography was just a hobby when he enrolled at the Photographic Society of Singapore in 1989. But today it has evolved into a medium to tell the stories of disadvantaged people, especially the children. “Since 2008, I have been using photography to advocate the rights of children who have been forced to work in hazardous environments.” He is also vocal about not treating them as mere subject materials. “Often, street children or impoverished families are seen as good photography subjects, and not as human beings,” says Tham. “Part of what I have been doing, both intentionally and unintentionally, is to change that mindset.

It should not be an exploitation, but an opportunity to advocate conditions for children facing hardships.”

His mission has taken him to Cambodia where he works closely with the village communities in Phnom Penh and Kratie. “I have initiated a scholarship programme that is now benefiting 60 scavenger children in a Phnom Penh slum. These children now attend an international school and are doing really well with five of them clinching the top two positions in their respective levels,” Tham explains. “In Kratie, I managed to raise funds to recruit nine teachers who are coaching 300 students from two extremely poor villages.”

Currently, Tham is working in Manila, concentrating on the landfill and charcoal-manufacturing communities. There are approximately 10,000 children living in hazardous conditions with many deprived of any kind of education. “I visited Philippines several times, and have always been interested in the living conditions of those working in the charcoal factory as well as the scavengers in the dumping grounds,” he says. His usual approach is to meet people first and focus on photography later. “I came into contact with the residents in such places and began to listen to their stories. I realised once again that people do not want handouts, maybe just a hand up…they simply want to be recognised and valued.”

“I realised once again that people do not want handouts, maybe just a hand up…they simply want to be recognised and valued, just like you and me.”

— Thomas Tham, former social worker who now works with children in the slums of Manila

Along with a couple of pastors who were also working there, Tham started several programmes, and is happy to note that today there is a good number of children attending school and taking part in other activities. “We have a feeding programme that we would like to sustain and expand. I am encouraged to see the community come together for their children. The parents get involved in our projects too,” he adds.

Tham’s mission is not without health hazards. “I was infected with the Hepatitis A virus in January 2013. I would have died if not for the care of the local community in the Manila landfill where I’ve lived before. They took turns to attend to me until I recovered. Even the doctors in Singapore said it was a miracle I survived without proper medical facilities,” he says. There are other obstacles as well, such as threats from syndicate gangs who exploit these communities. The rewards, however, far outweigh the challenges. “In this journey, I have made a lot of friends, learned their ways of life and seen their resilience. Through photography, I hope to mobilise resources towards a meaningful course.” Plans are afoot to expand these programmes to countries like Thailand and India.

To budding photographers, especially those who want to contribute to society, Tham’s advice is simple: “Be mentally present, be respectful of your work and of yourself, but most importantly, be respectful of your human subjects. Even if you never get to talk to a person, understand you will be presenting them to a public, and you will do right by doing so in a sensitive and respectful way.”

Children in many third-world countries are forced to work; Tham tries to raise awareness for their plight through his photographs that capture the harshness of their reality.