Stories > Compassion In A War Zone

Compassion In A War Zone

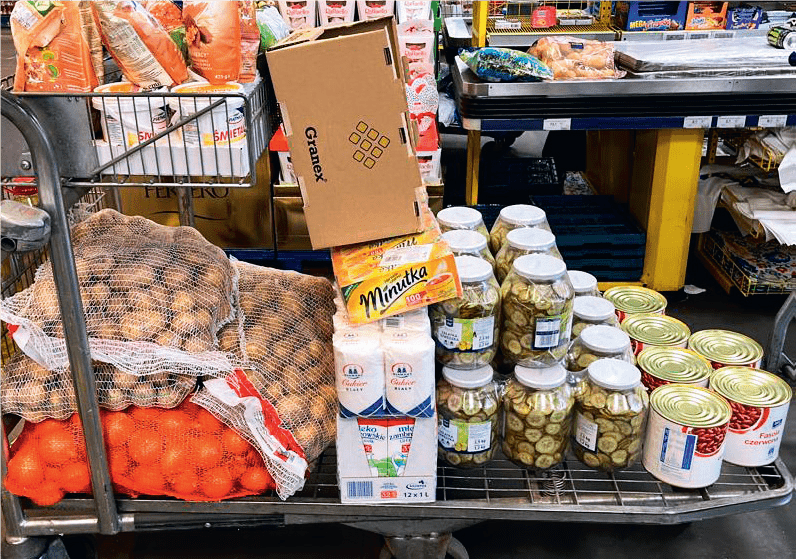

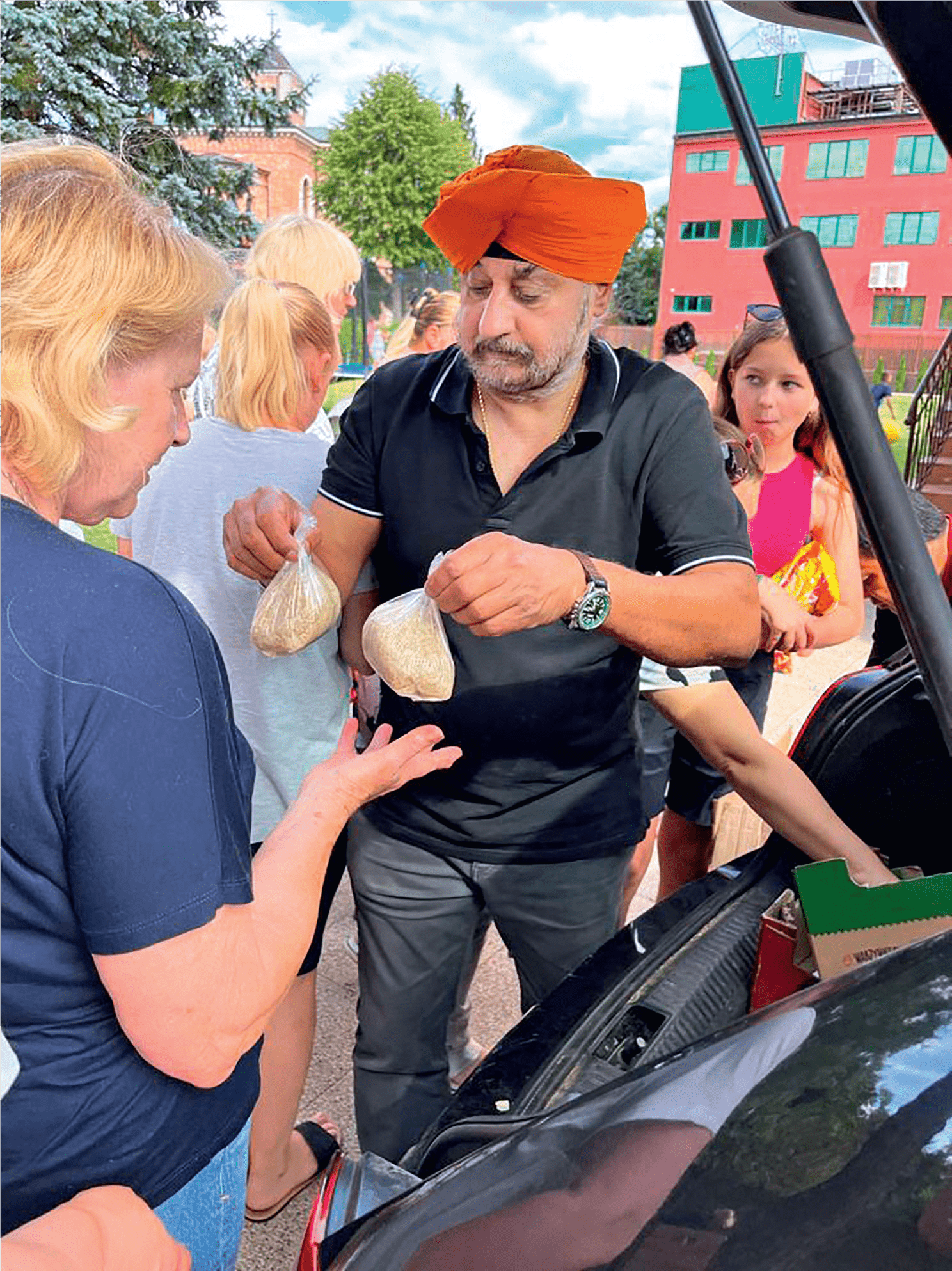

Two Singaporean volunteers start a food charity in Poland for Ukrainian refugees displaced by the ongoing war in their country.

BY ALYWIN CHEW

Both local and expatriate volunteers gather every weekend to help the needy in Warsaw; Ukrainian refugees were welcomed in Poland.

nly a few among us would run towards instead of away from the proverbial fire. Even fewer would do so when the crisis is taking place thousands of kilometres away and has little impact on one’s own life.

Among those in this latter group of exceptional individuals is Singaporean Priveen Suraj Santakumar, a business executive who left the safe confines of Singapore in March 2022 to travel to Poland to help the hordes of Ukrainians fleeing the war in their country.

Making matters more perplexing, the 35-year-old was not part of any humanitarian mission. He did so completely on his own accord. Priveen recalls that he was working at a Covid-19 isolation facility in Singapore when he watched on television the news of the war in Ukraine. Perturbed by the images he saw on the screen, he contacted his friends at the Rotary Club of Singapore, where he had been volunteering, to find out more about the situation.

The club then got in touch with its Polish counterparts and set up a Zoom meeting with some Ukrainians who were hunkering down in underground bunkers.

“There were hundreds of Ukrainians in bunkers and they had little to no food and water. They were surviving on water which they got from melting ice. Seeing such scenes made me feel like I needed to do something to help,” says Priveen.

“To be honest, I didn’t really have a game plan. I just wanted to put myself out there and be of use in any way possible.”

Charanjit Singh Walia has lived in Poland for the past 29 years; Walia’s charity distributes cooked food to homeless people. Singaporean Priveen (right, in blue cap) travelled to Poland to lend a helping hand to the Ukrainian refugees.

A BRAVE DECISION

Armed with medical supplies and a burning

desire to do good, he sprang into action

the moment he landed in Warsaw — the

outreach was facilitated by the Rotary

Club of Singapore — on 24 Mar 2022,

helping fellow volunteers manage the

refugees streaming in from the Poland-Ukraine border. The next night, he entered

the western Ukrainian city of Lviv to help

evacuate people.

Over the course of a month, he took on a variety of tasks such as visiting shelters to distribute blankets, offering a listening ear to Ukrainians fleeing the chaos, and putting his culinary skills to use by cooking fried rice, potatoes and sausages for starving refugees.

Charanjit Singh Walia sold his thriving restaurant business in Warsaw to serve the needy and homeless people in the Polish capital.

Among the many volunteers he worked alongside was a fellow Singaporean, Charanjit Singh Walia, a retired restaurateur who had been cooking Indian vegetarian meals for refugees since the crisis started in February 2022.

But unlike Priveen, Walia is no stranger to Poland, having lived in the country for the past 29 years. He shares that he wanted to venture out of Singapore for business prospects, and after visiting both London and Warsaw, he settled on the latter as the Polish city felt more novel than London, where there was already a sizeable ethnic Indian community.

“I would say that Poland chose me. I’m now part of the fabric of Polish society and even learnt to speak conversational Polish, which is actually quite a tough language to master,” he says of his move to the Eastern European nation. “Like most Singaporeans, I love to eat, which prompted me to start a restaurant. I learnt everything about running a restaurant on the job.”

Having sold his restaurant business, Walia, 65, now devotes all his time to helping the needy and homeless by giving out free meals to them through his charity, Warsaw Seva, in the Polish capital since 2017. The term “seva”, he notes, is derived from “langar seva”, which refers to the Sikh tradition of providing the needy with food.

“I was driving in the Warsaw city centre one day when I saw a homeless man retrieving a fast food wrapper from the rubbish bin. I could see the smile on his face when he found the half-eaten burger. He was looking to the sky, as if thanking God for the food,” he recalls. “That was when I told myself I have to help.”

“Many people thought that the

charity was a temporary initiative,

but when I continued doing it even

during the Covid-19 pandemic

when most other charities had

discontinued their operations,

they became more appreciative.”

Charanjit Singh Walia, founder, Warsaw Seva Association

Walia recalls that when he first started the initiative, locals were sceptical about the motive. “Many people thought that the charity was a temporary initiative, but when I continued doing it even during the Covid-19 pandemic when most other charities had discontinued their operations, they became more appreciative,” he says.

To fulfil his goal of feeding the needy, he went to the extent of declaring an early retirement — he sold his restaurant to fully devote his time to setting up a charity foundation that could legally receive donations. To date, Warsaw Seva has provided some 100,000 free meals to the needy, including Ukrainian refugees.

Besides spending some 18 hours a day cooking meals for the refugees, the Singaporean also opened up his home to a family of refugees for several months.

LESSONS FROM A WAR ZONE

For Priveen and Walia, who were

nominated for the 2022 Singaporean of the

Year award — it recognises inspirational

citizens who show extraordinary acts of

kindness, bravery and creativity — being on

the frontlines of the humanitarian efforts

has been a deeply sobering experience.

Warsaw Seva volunteers serving food to the needy in the Polish capital; Priveen went right up to Lviv, a city in eastern Ukraine across the border from Poland, to help fleeing refugees from the war-torn country.

The most poignant of lessons was on the dichotomy of human nature. In stark contrast to the selfless efforts of the volunteers, unscrupulous Polish taxi drivers could be found at the border crossings, charging as much as US$1,000 to transport refugees to the city centre, recalls Walia. Fortunately, the situation improved quickly after the Polish authorities took steps to ensure that the refugees were safely transported to shelters near the city centre.

“I have also witnessed incidents in which a minority group of refugees started to take advantage of the hospitality of the Polish. Some even felt entitled to the special treatment because of their circumstances,” he says. On the flip side, Priveen was floored by how most of the Ukrainians showed compassion despite being in the predicament they were in.

“I think the most heart-warming

thing I saw was refugees declining

my offer of an extra serving of food

– they told me to give it to others

who have not eaten.”

Priveen Suraj Santakumar, Singaporean volunteer in Warsaw, Poland

“I think the most heart-warming thing I saw was refugees declining my offer of an extra serving of food — they told me to give it to others who have not eaten,” he says. Some Ukrainians who spoke English also struck up conversations with the Singaporean, who admitted that he shared tears with those who recounted to him the heinous atrocities of war they witnessed.

“Some thanked me for coming all the way from Singapore to help. Others recounted how their father or uncle were killed or their neighbours were raped. Some told me how the Russian soldiers forced Ukrainian men to watch their wives and daughters get executed,” he recalls. “It felt as if they were narrating scenes from movies, except they weren’t.”

Both men also shared the consensus that the Polish are incredibly welcoming people. While Walia cites this point as one of the main reasons he has resided in the country for so long, Priveen concedes that he was surprised at this.

“I do not know why but I initially had the impression the Polish were cold,” he says pensively. “But after this experience, I have come to know that they are a loving and welcoming people. They were always ready to lend me a hand.”

NEW PERSPECTIVES

When asked if this experience has resulted

in new perspectives to life, Walia says that

the heart-wrenching scenes of despair got

him introspecting on how unfair life can

be. “It also made me realise that we really

should not take anything for granted. Life

can change in an instant,” he says.

The experience has had a profound impact on the way he goes about life, Priveen admits. Today, before making a big purchase, he asks himself if the money could be better used as a donation.

“I was recently contemplating buying a new pair of spectacles that cost $500. But when I converted the price into Polish zloty, I realised that this amount of money could probably feed 30 to 50 refugees for quite some time,” he recalls.

“This experience made me think about life. Is it about just enjoying what we have? Or is it about lending a helping hand to others? “My answer? Helping others,” concludes Priveen.