Stories > Designing For Resilience

Designing For Resilience

DESIGNING FOR RESILIENCE

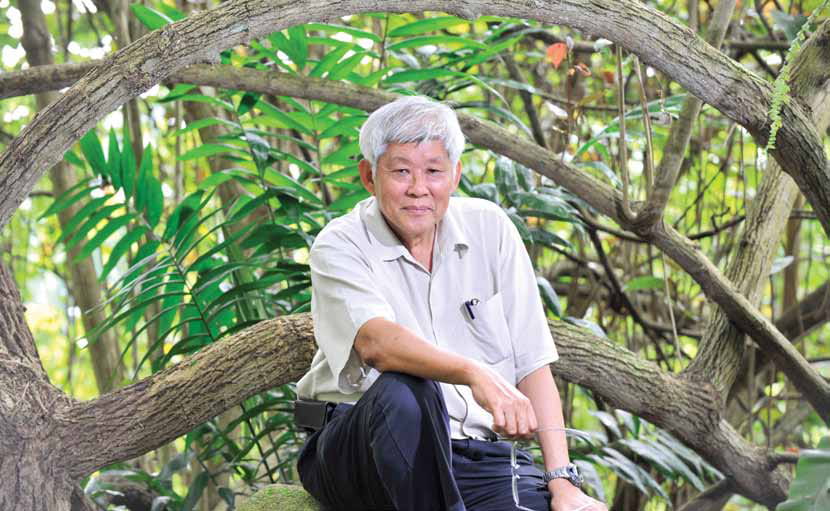

Acclaimed architect Tay Kheng Soon rethinks his career in the light of doing more for society,shares his thoughts on the need for today’s young to experience nature, and his idea for bridging the growing global urban rural divide.

By Kim Lee

any young Singaporeans expect a rewarding career after years of schooling. Tay Kheng Soon graduated like them, and saw himself as an architect whose most important purpose was to design good buildings. After 40 acclaimed years in architecture,he sees it isn’t good enough.

Tay, still a practicing architect and currently adjunct professor at the National University of Singapore’s School of Architecture, believes Singapore’s youth must change their approach in preparing themselves for an uncertain future. Architects, for example, need to design for total environments that address well-being in the broadest sense.

SG: The world has seen social, economic and ecological shifts since you became an architect in1964. How has this redefined your work?

Tay: Architects have to become social and environmental activists taking on issues and synthesising new design strategies. This means that architects have to have much more knowledge, ability to empathise, and to collaborate with a wide range of people to shape the human and natural environment. Right now, design is predicated on making the delectable object, be it a thing or a building.

The Mechai Bamboo School in Buriram,Thailand was visited by participants of SIF’s Friendship Express 2012.

As Paul the apostle said, “When I was a child, I thought as a child. Now that I am a man, I put away childish things.” Today’s economy manufactures consent through consumerism, and architecture is just another consumer product. The protraction of adolescence is necessary to increase the buying. This is the logic of contemporary design fetishism. Anyone concerned with the environment has to understand that the cause is extension of adolescent appetites. Maturity is when these appetites abate.

An example of my own professional change is my involvement in designing and realising the Mechai Bamboo School in Thailand,an experimental school for 180 students in Buriram, the poorest province in Thailand.

I deliberately used familiar village forms but in slightly unfamiliar ways to demonstrate that one can be very advanced without the glass and concrete box-look. The classrooms have a tall two-tier roof with the lower roof serving as a large overhang, eliminating the need for walls. An open classroom is thus created surrounded by greenery. Familiar yet different, the children love the school and garden atmosphere so much that they want to come to school even when it is shut over the weekends and holidays!

Mechai’s design process was very different from the usual process in Singapore. The architecture resulted from the school’s teaching philosophy. The classroom is an interactive space.Students learn through projects, not textbooks. They use the Internet with satellite links enabling global connectivity even at this remote location. This is the new world!

Students elect projects that help their families improve their livelihood. Teachers support the students’ projects with science,maths, history, geography, etc. Students do not take exams. They learn by doing community work, working in small teams to helps lower learners learn with the faster ones. Classrooms also serve as committee rooms where students participate in teacher selection and the school’s purchase meetings. This is empowerment!

The Thai Ministry of Education insisted on testing the students and were surprised that they ranked in the top 10% of all Thailand!The school has since been host to a stream of visiting teachers wishing to learn from it.

“This experiment (Mechai Bamboo School) taught me the power of liberating human capacity through trust and belief inhuman goodness.”

Mechai illustrates the new ideas about architecture. I have become a co-conceptualiser and catalyser of projects and ideas…no longer merely a consultant architect but a designer in the new comprehensive sense that the changing world needs.I am so glad to be a part of this experiment. It taught me the power of liberating human capacity through trust and belief inhuman goodness.

SG: How did you learn to appreciate the natural world? Why do you feel this is important?

Tay: Appreciation of nature is ultimately appreciation of oneself.Nature is not just out there, it is also in here — a point often missed.

I spent my childhood in Cameron Highlands (in Malaya then)during World War II. My family lived in a little house within a vegetable farm at the foot of the Boh Tea plantation. It was idyllic. I remember applying compost with my bare hands on to chilli plants with no qualms at all. I plucked raspberries, climbed guava trees, caught dragonflies, blew clouds of breath in the morning chill…. I guess all these experiences awaken deep natural propensities embedded by evolution in every human being. I am no different. Thus I am concerned for young Singaporeans growing up in a concrete environment, deprived and therefore fearful of natural things. I fear they deprive themselves of developing instincts that would serve them well, directly or indirectly. If these natural impulses are present, people will see things more holistically rather than as separate entities, which make them easily dictated to by the imperatives of today’s urban industrial culture — like being strapped to jobs they don’t enjoy,tied to heavy mortgages, stressed out by children’s school woes,and needing distraction through lots of retail therapy and other forms of compensation.

Paradoxically, resentment is growing in people against the impoverishment of their lives even as their material conditions improve. It appears the Maslowian prescription is changing;self actualisation is a demand at every stage of the hierarchy of human needs!

SG: In 2011, you helped set up Kampung Temasek,The School of Doing, in Johor, Malaysia, as an outdoor laboratory for Singaporeans to explore the natural environment. How is it doing?

Top and above: Tay Kheng Soon discussing plans for Kampung Temasek with volunteers; Eco-sensitive huts for guests at Kampung Temasek are built with recycled timber and local materials like palm stems. The four-person huts are solar-powered and designed to catch rain. Their construction was sponsored by private individuals.

Tay: Kampung Temasek came about from a conversation with some friends and Jack Sim, who donated the 4-hectare parcel to the project for 20 years. The idea of a “School of Doing”came from friends who were concerned that their children were growing up, in their words, “absurd”. Children nowadays are hooked on computer games and, when not, it is shopping.Their lives are divorced from nature and physical activity. The head, heart and hands are disconnected. This disconnect hampers efforts at fostering a creative society. True creativity needs integration of all human faculties.

Kampung Temasek’s credo is the other 5 Cs: Courage,Curiosity and Creativity, when infused with Compassion, allows the full flowering of human Collaboration to come about. This is what it set out to do.

It is not easy breaking from the mould. Through well wishers and out-of-pocket financing, Kampung Temasek has completed its first phase and is preparing for its second phase.Much more funding is required. Meanwhile, it has developed a large volunteer base and hosted many schools, teachers, and the Academy of School Principals, who gave it the thumbs up.Slowly, we are making progress. What is important is that it has stimulated many people to want to integrate the Kampung Temasek programme into Singapore. There is a workinggroup discussing establishing a new experimental school in Singapore, which is getting support from young married couples who want to ensure that, when they have children,their kids can go to a school system which provides great learning without the stress.

SG: You have travelled much and learnt much. How has that changed your work and life today?

Tay: My travels and experiences are opportunities to reflect on Singapore. As I see the challenges of development everywhere,I ponder what “development” should be. I am increasingly critical of development defined only in material terms,patterned on the Western Industrial Consumption model.Clearly, this is the cause of the social disparities and selfish values which cause environmental and social degradation wherever disparities get out of hand.

In my visit to Chinese villages, I was appalled by the human degradation of children left behind to be minded by tired old grandparents among neglected fields and unkempt village houses. I am equally appalled by the slums of Manila, Jakarta, Bangkok, Kolkata, etc. I have stopped being enamoured of slick glass-box architecture. Indeed, I find them repulsive, even immoral! But feeling this way is not good enough. What should one do about it? I had to rethink everything I knew and felt about architecture.

“Rubanisation provides the context to work, live, learn, play,farm and heal in new urbanised rural settlements.”

Tay listens as Myanmar Democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi makes the suggestion of prioritising housing for villagers. He was invited to present his Rubanisation concept to conference delegate sat Myanmar’s first Green Economy and Green Growth forum and conference in 2011.

In Manila with my urban design students from National University of Singapore to study the slums along the Pasig River, we were struck by the cheerful yet degraded way of life.The crime, squalor, corruption and garbage that clog the river are self-evident, and well-meaning humanitarian initiatives attempt to help. The system reaches equilibrium. Nothing changes. I realised that helping the poor is no solution. The phenomenon of the urban slum is a symptom of the failure of the countryside. The solution lies in the countryside. My ideas for resolving the rural/urban dichotomy were formed in Manila— “Rubanisation.”

SG: What is Rubanisation, and how do you think it will improve things?

Tay: I coined the term “Rubanisation” to describe the concept of rebalancing the disparity between the city and the countryside.It offers a different idea of “development” where more resources are diverted from cities to the countryside. Failure of the countryside results in the drift towards the city. As long as rural poverty is not addressed, all efforts towards the urban poor area drop in the ocean of poverty and degradation. Rubanisation provides the context to work, live, learn, play, farm and heal in new urbanised rural settlements. It serves the 99%, while the city serves 1%.

Like all new concepts, it takes time to sink in. The situation also has to be right. The global economic crisis signals the need to rethink the big city, export-oriented, developmental model. A more equitable model needs to come about. Thus Rubanisation, which has been incubating for seven years.

A Memorandum of Understanding has already been signed to do four Ruban settlements in northeast China. I have just returned from Sri Lanka this June where, at the invitation of the Ceylon Institute of Builders, I presented the keynote on Rubanisation and its relevance to Sri Lanka at their conference on Socio-economic Sustainability through Rural Urbanisation. My paper fitted exactly the agenda. I also had the privilege to meet Aung San Suu Kyi at the Green Economy and Growth Conference last year. She told me to pay attention to the villagers. I had also presented Rubanisation at the 2011 India-Japan Summit, in the context of the establishment of the Ganges Basin agricultural corridor. Right now, what is exercising my mind is the establishment of a “Ruban Bank” that mobilises crowd funding to finance uplifting of rural areas everywhere.

SG: You have been a keen observer of Singapore as it grew into independence. How do you feel about the country as it progressed?

Tay: Singapore went through different stages. The challenge is always among three poles: marketisation, social protection and emancipation. This is a dynamic process.

In the early days, the genius of the PAP (Singapore’s ruling party) was to balance the population’s needs with the needs of international business. Social protection got the votes, the cheap public housing program stabilised their power while also serving as wage subsidy and, with suppression of left wing labour agitation, it created the investment climate for economic growth.

Emancipation of the human initiative is now Singapore’s key challenge if it wants to prepare its people to meet the unexpected, which the future will inevitably throw up. Resilience and creativity have to be nurtured, but there is fear it may get out of hand and erode the preeminence of power. The will to change is restrained. There will be dithering as Singapore emancipates its people. Old reflexes and mindsets are at stake.

SG: How have you seen Singaporeans change with progress?

Tay: The 2011 general election and the recent by-election are indicators. The hotly contested Presidential election also showed a new interest in public matters. Once the lid is lifted… old grievances come up. Some will urge that the lid should never be lifted while others want it lifted judiciously. My feeling is that the tide of history cannot be thwarted and the speed of lifting the lid will be propelled by events possibly beyond our control.

SG: What Singapore values do you champion or think we need to change, to learn?

Tay: My pride is tinged with disappointment. Disappointment because it can do so much more.

Even as I acknowledge Singapore’s great administrative achievements, I regret the lack of internalised values. The streets are clean not because people take it upon themselves not to throw rubbish, but through punishments and employment of cheap labour to pick up the mess Singaporeans leave everywhere.

Tay’s concept of Rubanisation is a marriage of the rural and the urban in walkable settlements no larger than a kilometre square, surrounded by farms to support non-farm jobs. Rubanisation was conceived to correct the disparity between the rural and urban areas, to stop the drain of people, money and resources into cities, and revitalise the countryside by making it accessible to everyone.

“Being a citizen of the world is the natural state of human consciousness. Tobe otherwise is parochial, small-minded and ignorant.”

For self pride and identity to form, there must be belief in the goodness of people. This is a sea change from the dim view of human nature that underpins the rules, regulations, incentives and disincentives that make up everyday reality. Where to start? I suggest through the establishment of community-based enterprises and a new type of live-in schools. I can expand much on this but it is too involved to do here.

SG: Do you think social responsibility has a future in Singapore?

Tay: The next generations are navel gazing. The Singapore story has failed to ignite any idealism in them. Until it does so by word and deed, the young will continue not to raise their sights.

Yet, all my students constantly talk about creating community— that mythical state of togetherness they yearn for but eludes them. They do not have any idea what it really is nor how to engender it. Singaporeans know about the issues of human rights and sustainable living but lack the ability to imagine how to take action. One of my brilliant students who did a dissertation on co housing formed this dictum: “Community only comes only from successful sharing.”

If society is merely consumers of government agency then there is no need to share the work and no real need for community. Conversely, unsuccessful sharing will destroy what little community spirit there is! I would therefore say that if Singapore is to become a resilient, creative and cohesive society,then the new generations have to successfully create community through exercising common purpose.

SG: What does global citizenry mean to you?

Tay: Being a citizen of the world is the natural state of human consciousness. To be otherwise is parochial, small-minded and ignorant.

Awareness of what is happening in the world is unavoidable, though entertainment and sports do deflect attention from world events and issues. Economic upheavals,climate events, haze, etc, will impinge on cosy mindsets.Whatever happens in the world affects Singapore, even though cushioned by government policy. The full impacts have so far been shielded from Singaporeans too well. As a result, the Singaporean notion of global citizenship is still in its infancy.Exposure to the under classes in other countries tugs at heartstrings and serves as a lesson in gratitude for Singapore’s blessings, but more can be done to conceptualise the structural nature of social, cultural and environmental in justice at home and elsewhere. It is a mindset issue. Until a link into the connected nature of local and global issues is realised, the full value of an expedition into poverty is not gained.