Stories > Drawing On Human Experience

Drawing On Human Experience

American designer Tim Kobe, who worked with Steve Jobs to create the blueprint for Apple retail, says design thinking can continue to solve challenges in Singapore.

BY CARA YAP

ILLUSTRATION KEN LEE

n his hefty tome, Return on Experience, Tim Kobe drew similarities between the late Lee Kuan Yew and Steve Jobs. He had famously worked with the latter to design the minimalist, customer-experience-forward Apple stores that transformed retail and spawned countless derivatives. Both “design leaders”, the American architect suggests, were focused on building things that would impact the lives of people. This was made possible by dint of the visionaries’ apparent knack for “finding solutions that offer the best possible fit within the context”.

Viewed through the prism of that particular narrative, it is not entirely surprising that – following more than a decade of collaboration with the firebrand tech tycoon – Kobe, 64, would leave Silicon Valley for the tiny island nation whose founding father he had extolled.

“When I first decided to move to Singapore, I was attracted by the idea that everything in the country, from transportation to healthcare, had been given a degree of consideration before being developed. There are not many nations where you can say that,” he says.

HUMAN-CENTRIC DESIGN

The California native attributes Singapore’s punctilious approach to public design to its founding prime minister’s ability to toggle between the tactical and aspirational facets of nation building. “How do you rationalise planting 10,000 trees a year? The accountants would say that you are insane and that there is no real value to that. But it is rooted in a deeper concern for the liveability of people. That is an important design ethos to me,” he reasons.

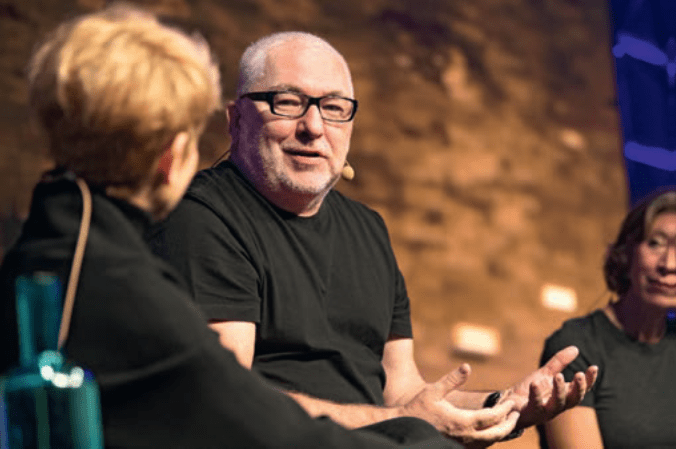

Kobe’s firm, Eight Inc., supports the National University of Singapore’s Industrial Design Programme. The architect also sits on the DesignSingapore’s scholarship committee that awards grants to aspiring designers. (photo credit: EY)

“THE IDEA THAT SCHOOLS HERE MAKE IT A POINT TO CELEBRATE EACH CHILD’S TRADITIONS AND HOLIDAYS, WHATEVER CULTURE THEY MAY COME FROM, IS PRETTY INTERESTING. IT EXHIBITS A COMMUNITY SPIRIT.”

Designing for human outcomes is something his practice, Eight Inc., is premised on. It has informed much of his firm’s work for brands such as Nike, Virgin and Ford. And since 2010, when the company moved its headquarters across continents to Singapore, it has left its imprint across the Asia-Pacific, undertaking projects for the likes of Temasek, Citibank and Lincoln. While setting up shop here was a relatively straightforward process, conducting business in a region with a diverse and intricate cultural weft demanded an understanding of varied social nuances.

“Working with a Singapore company, the culture of engagement tends to be a little more formal and structured. You get to the root of the question with a clear answer. Although, the rules of engagement are changing among younger Singaporeans, who prefer to assess personal values and determine an individual’s personality before talking business,” he explains.

Kobe is no stranger to learning unfamiliar folkways, having previously been married to a Taiwanese. As a new transplant in Singapore, he quickly cottoned on to its tacit societal norms. “When you look at people who fit the Singapore persona, there is a way they are expected to behave, and they expect others to do so as well. This is different from California, where there is less of that social pressure due to different cultural norms,” he says.

But can such structures become a sticking point that trammels creativity? “I feel that these are the qualities that Singapore designers can export – where you don’t just consider how things affect you, but how they affect your family, social structure and nation,” he counters.

STRESS BREEDS OPPORTUNITY

Kobe was instrumental in helping integrate design thinking into Singapore’s curriculum, as part of a cadre of creatives behind the Design 2025 master plan that aims to steer the country’s innovation-driven economy.

And he also appears to be invested in nurturing its next generation of designers, from Eight Inc.’s collaboration with the National University of Singapore’s Design Incubation Centre on its Industrial Design Programme, to his personal involvement in DesignSingapore’s scholarship committee.

Under the scholarship programme, he has helped stretch the horizons of budding designers, including a talented artist from a troubled background blighted by domestic violence. Upon his advice, she ultimately found fulfilment pursuing a degree in entertainment design, as opposed to a more conventional course in illustration.

Singapore-based American architect Tim Kobe has collaborated with the late Steve Jobs on the design of several Apple flagship retail stores in cities around the world.

“Working with a Singapore company, the culture of engagement tends to be a little more formal and structured. You get to the root of the question with a clear answer.”

Tim Kobe, founder and CEO, Eight Inc.

“There is probably a high percentage of the population who did not attain perfect test scores and are amazing at creative things that the more academically inclined would struggle with. I try to encourage those who may be left behind by the conventional idea of perfection, to open up a category of creative opportunities that typically exist in people who have been stressed,” he says.

According to him, opportunity is bred from stress, while intuitive design can improve the human condition. That may sound like a highbrow concept, but he points to its multiple applications, including strengthening the nation’s pandemic response. “I was vaccinated in Singapore, which was an efficient process. We have such linear procedures down pat here. But how do we, for example, allow all the hotels to get some share of the market as quarantine facilities? Design is well-suited to solve such complex problems,” he explains.

True to his non-binary line of reasoning, the designer is averse to ascribing values to nationality – though he admits to constantly encouraging his Singaporean colleagues to break rules and challenge assumptions in design. “I reckon these are more Eight Inc. design values as opposed to American values. I’m not one to wear the flag on my shoulder,” he says.

Local idiosyncrasies, however, are not lost on this Permanent Resident. For instance, he has learnt to embrace being called an “uncle” by strangers, having accepted it as a term of respect. Since moving here, he has remarried and has three children. The father of six – three grown offspring live in the US – finds inspiration at Gillman Barracks galleries and indie film theatre The Projector, though his younger children are partial to the Night Safari. Navigating their education system has also proven to be insightful.

“The idea that schools here make it a point to celebrate each child’s traditions and holidays, whatever culture they may come from, is pretty interesting. It exhibits a community spirit. It creates a mindset of openness rather than trying to confine you to your race, religion or nationality,” he reflects.