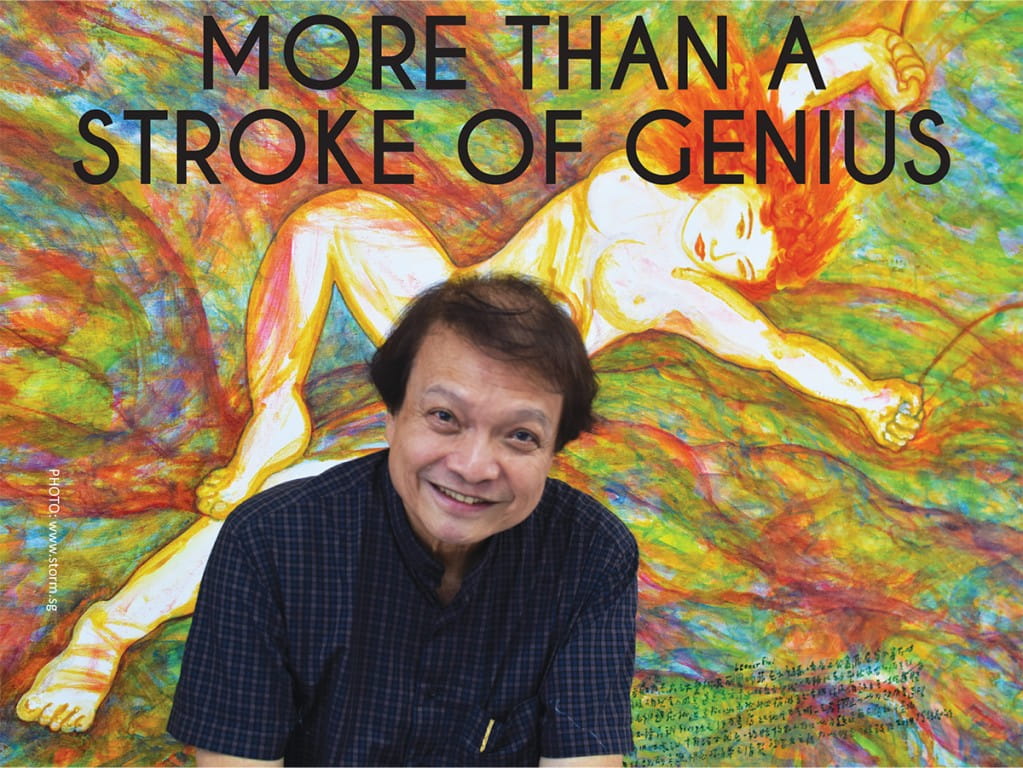

Tan Swie Hian with his latest work The Swing Is Her Only Flight; Homage To Leonor Fini, based on a meeting with the famous Argentine artist.

Cultural Medallion artist, thinker, philosopher, poet, painter and calligrapher. With more than 29 local and international awards, and over 23 solo exhibitions held locally and internationally since 1973, Singaporean artist Tan Swie Hian shares with us his personal life journey and passion for the arts. A prolific and inspirational artist, he has put Singapore on the world cultural map, while supporting the development of local artistes.

By Donna Cheng

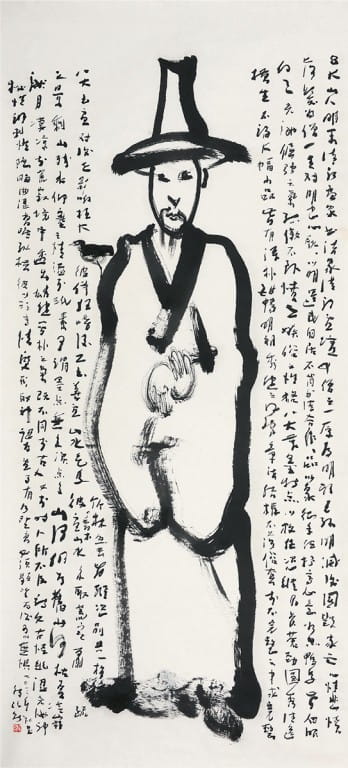

cclaimed Singaporean icon Tan Swie Hian is a multi-disciplinary artist known not only for his paintings, calligraphy, sculptures and large-scale works, often executed at lightning speed, but also for his poetry and novels. He made headlines in December last year when his ink-on-rice-paper work titled Portrait Of Bada Shanren — which he painted in 60 seconds and depicts a Buddhist monk — was sold for a record S$4.4 million at the 2014 Poly Auction in Beijing, a price which makes it the most expensive piece of art sold at an auction for a living Southeast Asian artist. This sale broke the previous record set in 2012, when his oil painting titled When The Moon Is Orbed sold at the same auction for $3.7 million. In his highly successful career that spans more than 40 years, he has picked up numerous accolades — he was awarded the prestigious Cultural Medallion award for Visual Arts in Singapore in recognition of his artistic excellence in 1987, and the Meritorious Service Medal, the highest honour for a cultural personality, bestowed by the President of Singapore, in 2003.

He is recognised for his artistic contributions in other countries too. In Davos in 2003, Tan was presented with the coveted Crystal Award, a prestigious award conferred by the World Economic Forum to outstanding individuals in recognition of their role in using arts and culture to foster global understanding. And in 1987, he was made a Member-Correspondent of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France — one of only 50 life members in the institute, and the only one from Southeast Asia.

Yet, these winning strokes of ink do not define this multi-talented artist, and his works do not adequately reveal the person that he is. After all, says Tan, his “works are but his craft”.

HIS EARLY STRUGGLES

In person, Tan is polite, unassuming, kind and gracious. For example, he believes in giving and receiving things from people with both hands even when casually handing a book. But his quiet, gentle manner belies a steely determination and focus to succeed. During his early secondary school days, Tan lost interest in his studies. His father, who owned a fleet of barges and ships ferrying commodities and passengers in Indonesia, wanted him to help in the family business. However, Tan refused and ran away from home. His life turned around when he met two inspiring teachers who spurred him on, and he developed an interest in literature and the arts.

In 1968, he started his first job working as a press attaché at the French embassy in Singapore — a job which he would hold for the next 24 years.

The most expensive piece of artwork by a living Southeast Asian artist. Tan Swie Hian’s Chinese ink on rice-paper Portrait Of Bada Shanren was sold for S$4.4 million at an auction in Beijing. Bada Shanren was a painter, calligrapher and descendent of the Ming imperial family who became a monk after the collapse of the Ming dynasty.

Unable to afford the luxury of being a full-time artist, he spent his nights and spare time writing and creating art. The same year he started his job, his ground breaking work, an avant garde collection of Chinese poetry, The Giant, was published. It was considered to be the zenith of the Chinese modernist literary movement in Singapore and Malaysia.

In 1973, he held his first solo exhibition, Paintings Of Infused Contemplation, which paved the way to more showcases of paintings in oil, Chinese ink, sculptures and calligraphy in Singapore and other countries.

Recounting his early years, he says without a hint of bitterness: “I could not be a full-time artist then. If I did, I may have to go begging. I could not drag my family and children down. I may lose my dignity and theirs. I could not do that.”

He never lost heart, and continued to do what he could as an artist and writer. “It is my mission, my calling. I just love literature and art.”

In Davos in 2003, Tan was presented with the coveted Crystal Award, a prestigious award conferred by the World Economic Forum to outstanding individuals in recognition of their role in using arts and culture to foster global understanding.

A peek into the first private art museum in Singapore — the Tan Swie Hian Museum. Built by private art collector Tan Tien Chi in 1993, this museum has since received numerous foreign dignitaries and famous artists from around the world.

One person in particular who stood by Tan in the early years was Michel Deverge, the French Embassy’s cultural attaché. He is the man Tan credits for getting him to continue with his art after he had devoted himself entirely to meditation for a few years in the 1970s. Deverge told Tan in jest that if he did not go back to painting, he would end their friendship!

Hence, Tan readily acknowledges his colleagues in the French embassy for being there for him. “They showed broad-mindedness and openness. They accepted me and treated me as part of the family. I am so grateful to them.”

INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION

Tan proudly calls Singapore his homeland. But he can jet around the world and feel right at home anywhere among people of different backgrounds and cultures, because of a shared love for the arts, culture, language and literature. This, he feels, makes him a global citizen.

Tan has put the spotlight on Singapore with his participation in more than 50 international group exhibitions such as the prestigious annual Salon des Artistes Francais art exhibition in Paris’ Grand Palais in the 1980s and 1991 and the Venice Biennale in 2003. He has also staged 23 solo exhibitions in other countries, like his exhibition of works at the World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland, in 2003.

On top of exhibitions, his art has been recognised in other ways. In 1998, he was selected by the United Nations, together with 97 other established international artists such as David Hockney and Roy Lichtenstein to illustrate a new edition of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. He also worked on a series of lithos with Nelson Mandela and 38 other artists for charity in 2004.

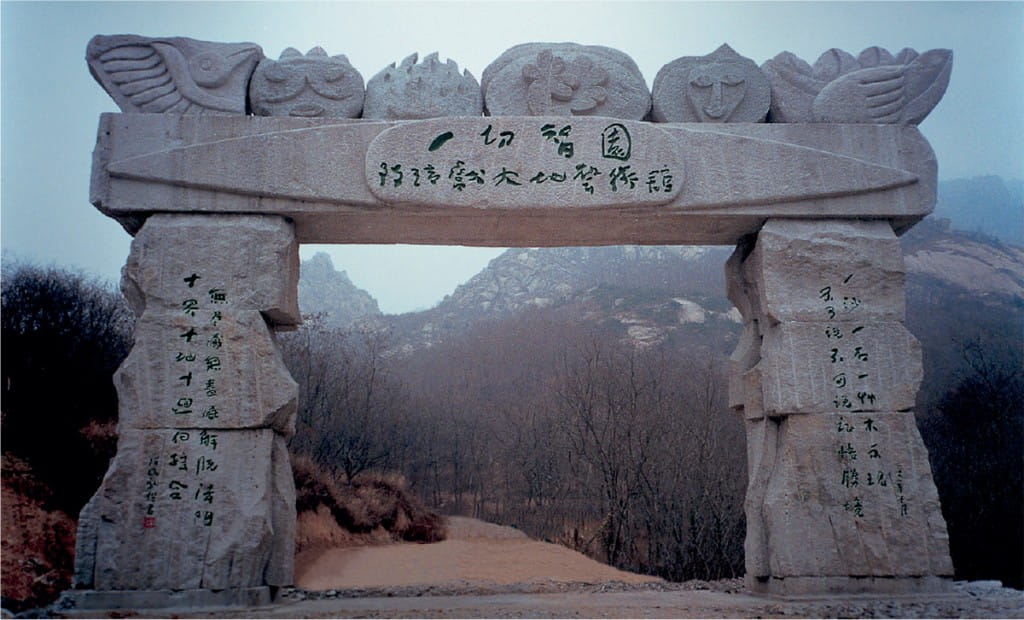

Tan has left his mark on China too. In 1996, he was picked to have his calligraphic works etched on the rock face of the Three Gorges along the Yangtze River, joining another 134 international artists’ artworks in forming the world’s first open-air contemporary Chinese art gallery. He even has a museum in China dedicated to his works: The All-Wisdom Gardens: Tan Swie Hian Earth Art Museum in Qingdao, China, which occupies a wooded mountain range of about two square kilometres, a space that takes a visitor more than four hours to finish touring.

“The arts connect and foster good relationships with people from different countries and beauty can make the world happy, he says, of his works extending their reach beyond Singapore.

Tan has also been invited to meet countless world leaders, and has hosted eminent personalities like Kofi Anan, the former head of the United Nations, at the Tan Swie Hian Private Museum, a repository of his art on Sims Avenue, in eastern Singapore, built by an art collector.

But Tan says he does not consciously think of his role as a citizen ambassador. “Everyone knows me as the artist from Singapore. I also represent Singapore the moment I step out and travel overseas. What I create naturally represents my country.

“Only when you are not conscious, does everything flow naturally, and it shows in different layers — of yourself, your country, your land, your spirituality.” Honest insights from a brave and talented Singaporean who has chosen to walk his own journey and stay true to his heart.

NURTURING SINGAPORE ARTS

Singaporean art, according to Tan, does not have a particular style, and should not be limited only to paintings or writings that contain recognisable local themes or icons. He adds that doing so would be to “pigeonhole” local works into prescribed forms, which will stifle originality and individuality.

“Everyone knows me as the artist from Singapore. I also represent Singapore the moment I step out and travel overseas. What I create naturally represents

my country.”

— Tan Swie Hian on his role as a citizen ambassador

“Instead, local artists should produce original works that emanate from who they are as individuals,” he says.

He has played his part in inspiring the development of the arts scene in Singapore. A number of his novels, poems and stories have been adapted and performed as visual theatre.

His story, Tang Huang (1985), for example, was adapted into a dance by Cultural Medallion for Dance recipient Lim Fei Shen, and his poem Two Rivers (1992) was choreographed by another Cultural Medallion for Dance recipient Ying E Ding, with costumes and sets designed by Tan himself. His collection of fables, Tone Poem On Fables (1999), was set to music by Cultural Medallion for Music holder Phoon Yew Tien, and performed by the Singapore Chinese Orchestra.

Staying true to his love for the arts and to support its development here, Tan generously donated his personal collection of more than 6,500 books, manuscripts, artworks and artefacts to the National Library Board in 2003. The donated works are now part of the library’s Tan Swie Hian Collection. Next year, he will hold an exhibition of his journals at the National Library.

Looking ahead, Tan says there needs to be depth for arts to flourish. This depth, he believes, comes with spirituality and philosophy, beyond just the development of the physical infrastructure.

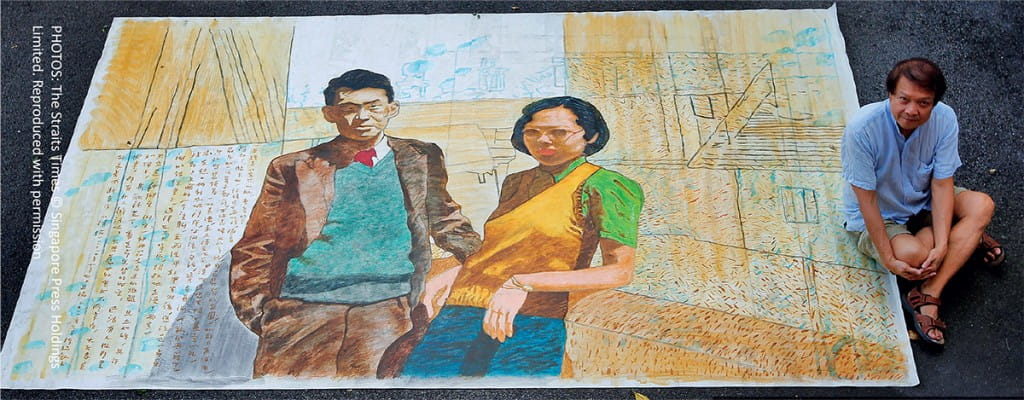

Tan Swie Hian sitting next to the 2.9m x 5.6m oil painting of a young Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister (1959-1990) and his wife, Kwa Geok Choo.

He says: “Younger artists need to develop the discipline to read, to feed the mind, and to have a historical sense so that their works have depth. Museums here can help by making it a priority to build up a good collection of local works.”

“The arts connect and foster good relationships with people from different countries.”

— Tan Swie Hian

SPIRITUAL SUSTENANCE

He meditates three hours a day, climbs a thousand steps daily, hand-washes his clothes and makes it a point to eat well to stay healthy. Tan considers meditation as a spiritual discipline. He says that it enables him to find inner clarity which helps him to create pieces when he feels he has a message to share.

A thinker who reads voraciously, Tan believes in enriching his mind. This has helped him upkeep himself, so as to stay confident of who he is as a person, and as an artist. When he is not travelling, he likes to work through the night in his quiet art studio tucked away on a street in Telok Kurau in Singapore’s eastern suburbs. The affable Tan calls himself the night watch as he works through the night till around eight in the morning.

Tan Swie Hian’s S$3.7 million oil and acrylic painting, When The Moon is Orbed, held the top spot for the most expensive artwork by a living Southeast Asian artist for two years until the latest record-breaking sale of Swie Hian’s The Portrait Of Bada Shanren.

The sprawling All-Wisdom Gardens: Tan Swie Hian Earth Art Museum in Qingdao, China. The mammoth museum covers a mountain range of two square kilometres.

A pensive person who also spends his nights reading and reflecting, Tan diligently journals his thoughts in words, Chinese characters and in sketches. From his precious notes, Tan’s thoughts are distilled and translated into his creative works of poetry and art.

A philosophical Tan explains his transition from a writer to the visual arts. “My literary works were deeply rooted in reality. Negative reality in terms of human sufferings. After my watershed year in 1973 (the year he had a spiritual illumination following the Buddhist teachings), my art became the art of happiness”. Tan feels his works should evoke feelings of joy.