Stories > Passage to Nepal

Passage to Nepal

Through the sale of second-hand books, former start-up maven Randall Chong aims to fund educational projects with long-term impact in the Himalayan country.

BY YE SUI LING

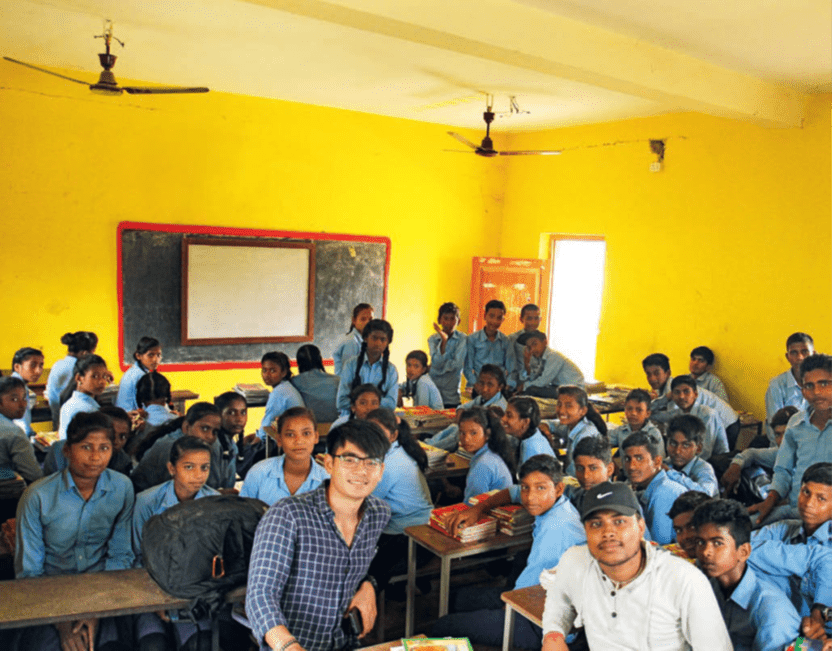

Singaporean Randall Chong (front row, with glasses) founded social enterprise Books Beyond Borders that helps to support education initiatives for underprivileged children in rural Nepal.

ovid-19 has exacerbated education disparities, and in Nepal, where schools were shut for over six months, a Unesco study estimated that 4.5 million girls were at the risk of dropping out.

Randall Chong is well acquainted with the faces behind the litany of grim statistics. Working closely with non-profit organisation Teach for Nepal (TFN) – which deploys outstanding university graduates to teach in remote public schools and train existing teachers – he was informed about girls being married off to alleviate economic hardship amplified by the pandemic, as well as a rise in the country’s suicide rate.

“Alcohol abuse sometimes runs rampant in rural Nepalese communities, which can present an unsafe environment for girls. Many often look forward to attending school as a means of escape,” he says.

Under such extenuating circumstances, TFN’s ground-up initiatives have received much needed support from his social enterprise, Books Beyond Borders (BBB). These projects involved broadcasting lessons over the radio and erecting mobile learning camps across far-flung villages.

BBB also funded 2,000 activity books for home-based learning, along with a support group for girls. Since its inception in 2018, the social enterprise has disbursed more than S$20,000 in educational grants in Nepal. Its pay-it-forward business model is sustained through the sale of donated second-hand books and cash donations. Chong, 29, also works with various non-profits, such as the local youth chapters of Rotary International, providing them with non-restrictive grants.

SEEKING PURPOSE AFAR

Disillusioned at times by the paradoxical nature of the start-up industry he worked in – where inflating figures to contrive an image of credibility is par for the course – Chong joined a trekking expedition to the Everest Base Camp in December 2017. He had never experienced hiking, or winter for that matter, but was determined to do it.

As it turns out, the first part of his wish was realised, when a week into his trek along a deserted trail, he noticed he was being tailed by a local. “I thought he wanted to kidnap me for my organs, as I had read unverified accounts of such cases,” he recounts earnestly. He later found out that the individual on his trail was, in fact, a 16-year-old porter who became his travel companion, guiding him in halting English.

“EDUCATION BUILDS CONFIDENCE AND DIGNITY, WHICH PUTS EVERYONE ON AN EQUAL FOOTING. MY END GOAL HAS ALWAYS BEEN TO FUND PROJECTS THAT TACKLE POVERTY, AS IT HAS A DIRECT IMPACT ON A CHILD’S EDUCATION,” SAYS RANDALL CHONG.

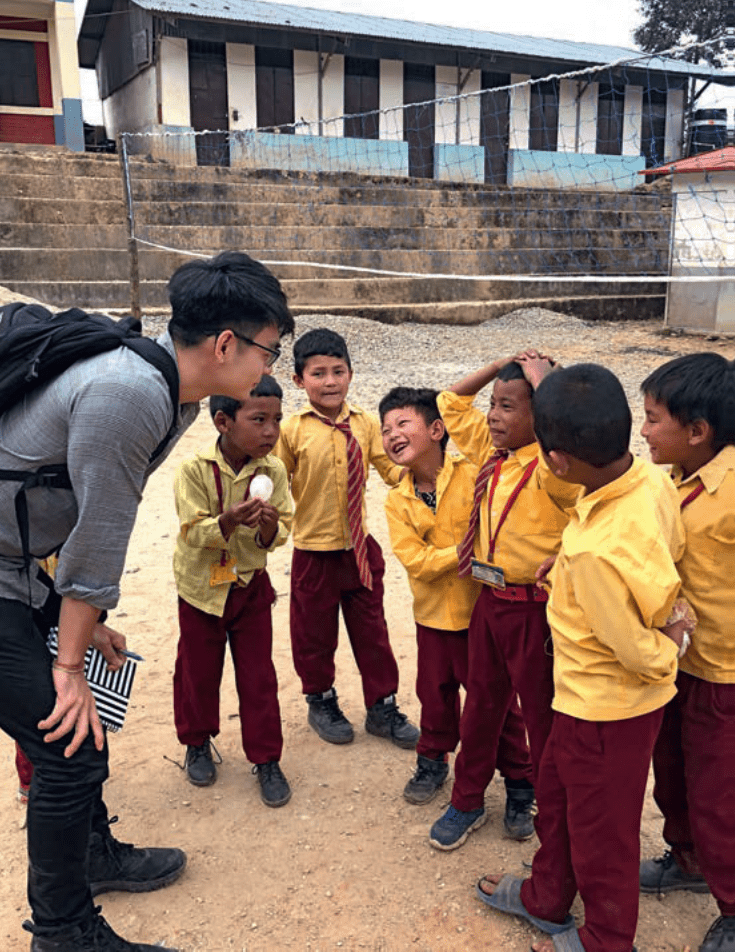

Chong has helped to distribute school essentials through the local Rotary Club in Nepal.

The seasoned backpacker’s mind swirled with questions, including why the teenager had stopped his studies. “I began wondering where kids went to school, as I had not seen one for miles. Why were girls working in the fields, and why did mothers look so young?” he recalls. Back in the city, he tried to find an opportunity to visit a local school to have his questions answered and help out in some way, but was unable to find one on short notice. Shortly after returning to Singapore, he received an invitation from the owner of his hostel in Kathmandu to visit a rural school. Chong caught a flight bound for Nepal the following weekend.

There, in villages a 10-hour drive into the mountains, he visited scuzzy public schools devoid of sanitation facilities, where he was shocked to witness students urinating outside classrooms – one of the reasons local girls often stay away from school.

He also learnt through the help of a translator that in Nepal’s public school system, principals do not have jurisdiction over teachers, who are typically hired by the local government, so a lot of them just don’t show up to teach. Literacy inequality is compounded by poverty, cultural norms that force girls to marry at a young age, and an entrenched caste system relegating students of lower castes to the back of classrooms.

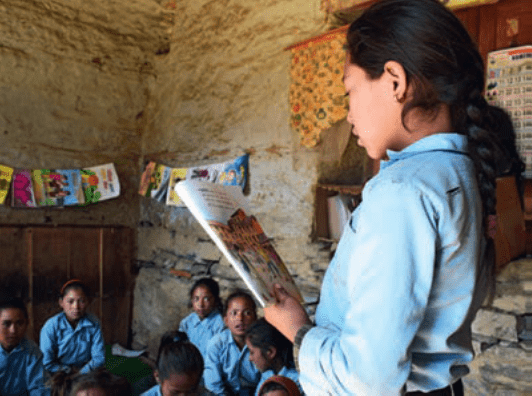

The social enterprise has disbursed over S$20,000 in educational grants to support initiatives such as education for young girls in the Himalayan nation.

Confronted with an issue wrought with complexities, and caught at an inflection point in his career, he quit his job and established BBB as a charity aimed at improving education in developing countries. Its first order of business? Raising more than US$10,000 in seven days by reaching out to friends and family, a successful endeavour that allowed it to distribute 669 bags of school essentials to needy kids through a rotary club.

Over the past three years, BBB has worked with numerous local non-profit organisations, but its most enduring partnership is with TFN, which benefits from the government’s support. The non-profit has reported improved attendance rates and lowered attrition across its schools, where alumni are known to return as mentors.

But according to Chong, statistics belie the true impact of quality education. “In developing countries, education builds confidence and dignity, which puts everyone on an equal footing,” he asserts. He recalls visiting a student from an impoverished community whose family spent a week’s savings to serve their guest a meal with bottled water. “He’s now the president of its English language club,” he shares.

BRIDGING THE DISTANCE

It’s such encouraging accounts that he seeks to document in raising awareness of their work. Obtaining them from TFN educators can be tricky, though. “Internet access is limited, and they may not grasp the type of stories I’m after,” says Chong, who asks them questions related to school and builds a narrative around it. He is now familiar with local cultural nuances. “Initially, I thought they did not sound enthusiastic in their replies. I later realised they were actually excited but just expressed themselves in a more reserved manner.”

He also cleaves to his counterparts’ hospitable nature, having been invited to tea and dance ceremonies. Conversely, they share a sense of mutuality with the mysterious Singaporean who schlepped his way into rural Nepal one day.

“Working with Randall has been a great experience. Despite language differences, we have never had communication issues,” comments Prajwal Khadka, TFN’s associate director of development and partnership. “Teaming up with BBB has reinforced my belief not only in the efficiency of Singaporeans but of their altruistic nature.”

Chong, who spends up to three months in Nepal every year, plans to start a dairy enterprise for the local women to help them uplift their income, which in turn will help the community to provide better education opportunities to their children.

“Working with Randall has been a great experience. Teaming up with BBB has reinforced my belief not only in the efficiency of Singaporeans but of their altruistic nature.”

Prajwal Khadka, associate director of development and partnership, Teach For Nepal

Though Covid-19 scuttled Chong’s travel plans, he has kept busy. Shortly before the pandemic, he launched an online store for second-hand books. Pivoting to a social enterprise model seems to have worked out for the one-man show, who reveals that for the first time in 2020, he received a salary from his venture.

He dreams of running the pre-loved equivalent of Book Depository, an online book retailer, and starting a dairy enterprise run by Nepalese women. The latter is aimed at supplementing the income of local households, most of which own buffaloes but lack the means to travel long distances to sell their dairy products at markets. “My end goal has always been to fund projects that tackle poverty, as it has a direct impact on a child’s education,” he concludes.