Stories > Paw Patrol

Paw Patrol

Saving the Malayan Tiger is a community initiative for non-governmental conservation organisation RIMAU.

BY SANDHYA MAHADEVAN

PHOTOS ISTOCK

RIMAU was founded in 2018 by documentary filmmakers Lara Ariffin and her husband, Harun Rahman, to protect tigers in their natural habitats in Perak state.

he tiger is an apex predator and plays an important role in maintaining the balance of the ecosystems they live in. Among the different varieties, the Malayan tiger, which is the national animal of Malaysia, was recognised as a distinct subspecies in 2004 and renamed as Panthera tigris jacksoni, in honour of British conservationist Peter Jackson.

Harimau (tiger in Malay) Malaya is the official nickname of the national football team, and its image is on the emblem of the Royal Malaysia Police. It is, sadly, also the most critically endangered species in Peninsular Malaysia.

“In the ’50s, there were an estimated 3,000 tigers here, but today we are at a mere 150 tigers,” says Lara Ariffin, co-founder of RIMAU, a non-governmental organisation focused on the conservation of the Malayan Tiger. The National Tiger Survey done between 2016 and 2020, the first of its kind in Peninsular Malaysia, showed a further decrease.

Indiscriminate poaching to meet the demand for tiger body parts, such as fur, bones, nails and even its whiskers, is one of the main causes. Extreme habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation — Malaysia has lost 55 per cent of its forests — is another.

Human wildlife conflict has resulted in the depletion of the tiger’s prey, elaborates Lara. The meat of the Sambar deer is popular in Malaysian cuisine and the animal has been hunted to almost extinction. Swine flu outbreaks have also affected local wild boar population. Both animals are integral to the big cat’s survival. “Our goal is to build the tiger population in Perak, a state in northwest Malaysia, to about 80. Anything below that is not really a viable population,” says Lara.

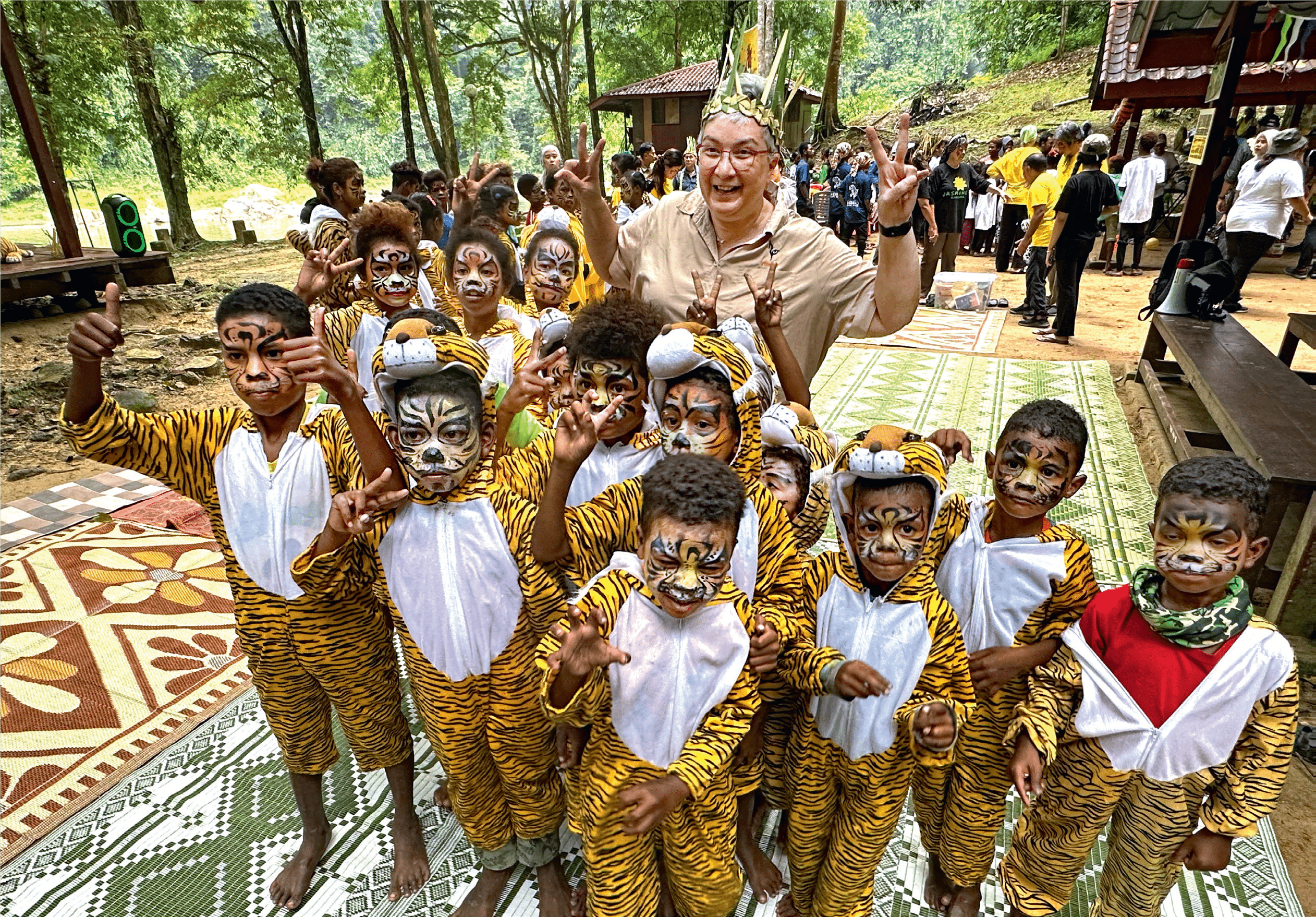

Lara works with children of the indigenous Jahai community to create greater awareness about conserving wildlife, especially the tiger population.

A LOVE FOR WILDLIFE

An architect-turned-documentary

producer, Lara founded RIMAU in 2018 with

her husband and fellow documentarian,

Harun Rahman. Both conservationists at

heart, their specific interest was triggered by a film on tigers they were both working

on in 2009. This threw them headlong into

research on the giant cats, revealing with

alarming clarity that something had to be

done about their dwindling numbers.

The alarm bells were already ringing by then, but it was frustrating that not much was being done, says Lara. “But rather than complain about the lack of action, we, along with some friends, decided to do something about it.”

As wildlife filmmakers, the couple were adept at spreading awareness, but what was imperative was putting enough boots on the ground to protect the forests. They were clear right from the start that conservation would begin and remain at community level — the people living closest to respective forests must be involved.

They found a like-minded partner in the Royal Belum State Park under Perak State Parks Corporation (PSPC) and began by first meeting with the leaders of the Orang Asli (the indigenous population of Malaysia) communities in the surrounding areas to create awareness on their mission.

“You cannot do conservation on an empty stomach,” asserts Lara. RIMAU recognised first-hand that all the people they were approaching had families to feed. “For us, this was one of the best ways to do it, while giving those that so desperately need financial assistance the ability to work with dignity, and in an area that they are comfortable with.”

The Malayan tiger has been classified as a critically endangered species.

THE LEARNING CURVE

RIMAU had its first set of patrollers in

2019 as they welcomed five members

of the Jahai tribe. These forest-dwelling

hunter-gatherers have lived alongside

the Malayan tiger for centuries and have intimate knowledge of its dwellings. The

team of patrollers was rightfully christened

Menraq, which stands for “the people” in

the Jahai language.

RIMAU follows the SMART Patrolling protocol, the methodology used by all enforcement agencies throughout Malaysia. It involves detailed recording of signs of encroachment along with GPS coordinates, which are then uploaded to a common database.

As most of the tribesmen were illiterate, the RIMAU team realised that they would not achieve anything from just a one-off training session. They began a six-month-long process to train them — from the basics of documenting and using the equipment, to even financial literacy, such as helping them open and manage bank accounts.

The main role of the Menraq Patrol is to walk the ground. This also includes keeping an eye out for poachers or anyone in the Royal Belum-Temengor forest without a legal permit, and to clear snares and traps. The petrol records all signs of animal or human activity: Measure the size of paw or footprints, photograph them, and enter as detailed a description as possible on the type of print or tell-tale sign, as well as the tiger’s estimated age.

Sufian Rahman, 21, joined RIMAU in 2021. Before that, he made a livelihood by selling honey that he collected from the forest and fish he caught from a nearby village. Having encountered elephants and bears, and even tiger paw prints in the course of his work, he was fully aware of the dangers involved in the work he would do for RIMAU. But the prospect of being able to save the forest far outweighed the personal dangers.

The Jahai are children of the forest, but what is most admirable is how well they are able to navigate the technology. Fahmi Jali, who has been patrolling with RIMAU since 2020, admits that it was a steep learning curve. “Initially, I thought GPS [Global Positioning System] was a phone,” he says, “but I soon learnt how to use it and also shared my knowledge with other members.”

Listening to the community is an innate part of the way RIMAU operates. “Working with the local communities, we have to first listen to them,” says Lara. “One also needs to manage expectations. We cannot expect similar work practices as city dwellers.”

On the same count, Lara was aware that city dwellers would not be able to navigate the dangers of the forest as deftly, carrying 20kg bags on their backs, loaded with equipment and supplies to last them while camping out in the forest.

The non-profit has also been instrumental in preventing logging in areas even outside the State Park. “We have stopped thousands of trees from being cut down,” says Lara. Although they are more a monitoring body than an enforcement agency, having more boots on the ground has helped the Malaysian authorities.

“It is important to do tiger

monitoring work because there is a

lot of poaching. I learnt about this

only after joining RIMAU.”

Fahmi Jali, volunteer patrol member, RIMAU

“It is important to do tiger monitoring work because there is a lot of poaching. I learnt about this only after joining RIMAU,” says Jali.

Initially launched with the help of friends, Lara (right, wearing a scarf) and her team have grown RIMAU from a ground-up campaign to an international award-winning non-profit.

FUTURE AS A COMMUNITY

Working with the Jahai people goes beyond

tiger conservation for RIMAU — it has

always been about building a community.

One of the things the tribals expressed

was that they would like their children to

get some form of education. With the help

of a new grant, RIMAU has been able to

organise a team of local teachers to come

in and teach the Jahai children.

Another important discussion that RIMAU has with the tribesmen relates to an interesting practice they follow — that of a communal money pool that gets topped up with RM10 for every day of work. Every six months, they have a discussion on how the funds would be used, says Lara.

For an organisation that originally started with the help of donations from friends, RIMAU is evolving and getting bigger. While RM50,000 from a generous funder kick-started the original Menraq patrol, RIMAU have since gained funding from many foundations, including the government-led Yayasan Hasanah, an independent foundation that supports impact-driven solutions in Malaysia through its grants and collaborations.

A video feature by the Singapore International Foundation’s storytelling arm, Our Better World, brought in further funding in the form of donations of over $1,000 (RM3,442). The story also garnered more than one million online views, and led to nearly 500 shares, comments and story actions on social media channels.

In July this year, the Menraq Patrol Unit won the IUCN WCPA International Ranger Award 2023 for its remarkable work in preserving and protecting natural resources. The unit was among nine rangers and ranger teams selected from 114 nominations across 52 countries.

Getting to this point has had its challenges, but their work is not over yet, says Lara. She hopes that some of the patrollers will move on to become full-time staff with the State Park.

“We have come to realise that what

we do goes beyond just saving the

tigers — it is about the community,

the forests and the entire landscape.”

Lara Ariffin, co-founder, RIMAU

“When you protect the tiger, you protect every other animal in the rainforest,” says Lara. “We have come to realise that what we do goes beyond just saving the tigers — it is about the community, the forests and the entire landscape. The tiger is the symbol, but it represents so much more.”

Scan the QR code

to find out more.