Stories > Powerhouse of Compassion

Powerhouse of Compassion

As an advocate of women’s rights, Dr Noeleen Heyzer has pushed hard to address the issue of violence against women. Growing up in a Singapore that was finding its feet instilled in her a passion to stand up for the downtrodden and the less fortunate. These instincts served her well when she joined the United Nations in 1982. In 2007, she became the UN’s Under-Secretary-General and Executive Secretary of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the first woman in the role since 1947. Now based in Bangkok, she focuses on inclusive and sustainable development in Asia.

By Kim Lee

SG: You’ve made a priority out of championing the underdog, particularly Asian women. What set you on this path?

Dr Heyzer: Growing up in Singapore at a time when the world was wrestling with struggles for political independence framed much of my thinking and my experiences. Colonies were grappling for greater freedom, independence and equality, and it transformed the world order. All this influenced me as I grew up in old Chinatown, an area of Singapore regarded as the “hotbed” of resistance.

When it came to championing women’s issues, it was based on what I saw growing up and written about around the world, like Pearl S. Buck’s The Good Earth, which looked at feudalism and patriarchy in China. I also read Ibsen’s The Doll’s House, about women in Scandinavian society. In the early 20th century, Ibsen had a profound influence on Asian societies in search of a “modern self”. His work was translated by Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, who asked in his famous 1923 lecture: “What happens after Nora leaves home?” He felt that the liberation of Ibsen’s protagonist, Nora, would be short-lived without a society fit for women.

SG: Is Singapore today a good place to be a woman, and what do you think of men’s role in society?

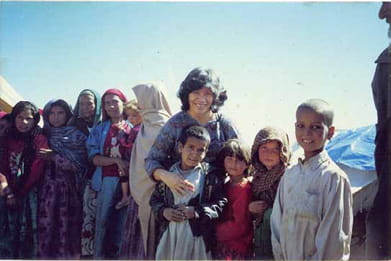

Dr. Noeleen Heyzer and children in Afghanistan during the first International Women’s Day celebration in March 2012 in Kabul after the fall of the Taliban.

Dr Heyzer: It depends on which woman, from which class and background. For rich, educated women, and now women like me who have education and status, of course it is a good place. But I am very sure that for the women who are migrant workers, household maids and factory workers, it is still a difficult place to make ends meet. That is why you find so many women not wanting to have children. There is still not enough support for families to have decent lives, so you have several household members having to work simultaneously because the cost of living is so high. I know the government has prioritised these issues and is providing institutional and financial support. However, I think a lot more can be done, such as rethinking some of the migrant worker levies.

The role of men is changing. I have been around some very supportive men, and seen and experienced very destructive men, so I am very careful about making stereotypical judgments. We need to understand the social systems in which men and women live and the social forces affecting men’s lives. Men who are unemployed, exposed to violence, and feel their egos threatened, are the ones who have great difficulty dealing with normal relationships.

SG: You’ve lived a life that appears guided by very strong principles. How did you come by them?

Dr Heyzer: I had very good ethical mentors. I grew up influenced by very deep thinkers and practitioners who believed in social justice. They were Jesuits and priests from the French tradition, who trained me through good literature, discussions and practice. I do have a strong moral compass based on my faith and strong spiritual values. This has strengthened my passion to contribute towards a more compassionate world.

SG: What have been the stiffest challenges you’ve faced?

Dr Noeleen Heyzer in Kosovo during her tenure as Executive Director of UNIFEM in 2006, with its Goodwill Ambassador Nicole Kidman. Some 85 women’s organisations from different ethnic groups and regions of the country are associated with the Kosovo Women’s Network, an important umbrella organisation and UNIFEM partner. Photo UNIFEM

Dr Heyzer: I have always valued education, but I had to work extremely hard to compete for scholarships for the privilege of education. In my professional life, I tend to be a bit of a perfectionist. I put my soul into my work, and am driven to realise social justice agendas. It is not always easy, because I am doing this in one of the world’s most complex bureaucracies, which is the United Nations. The struggles were sometimes difficult. A very good example is what we tried to do in Afghanistan to help women shape their society out of the peace process. It would be extremely difficult to deal with the warlords, but we felt that the voices of women and their leadership were important.

We wanted women to be respected from the very start, to take the lead in the formulation of the new constitution, and to put gender equality/equal citizenship rights as part of their constitutional rights. That process was not easy.

Equally difficult was what my UNIFEM team and I encountered to secure the passage of Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security, or earlier to get the UN to commit to ending violence against women. But we did it, and these frameworks and advocacy have changed social norms and behaviour. It was worth all the pain.

Security Council Resolution 1325 meant getting women to the peace table so that, for the first time, they could negotiate the political settlements that would take into account issues that were never really discussed, and that decision-makers could begin to understand problems of injustice at every level, as well as people’s own solutions to them.

It has been life-changing for many women and girls who experienced the worst conflict situations. We didn’t want them to be seen as victims but as agents of change, and to use their experiences to shape a more just and sustainable future for them. We wanted people to understand the impact of conflict and wars on the lives of women, girls and the men in their lives, on their villages and their communities; for example, issues of rape babies, land rights, and education for married girls. I met so many girls in camps — girls who were kidnapped and forced to become soldiers. Many of them had children. In the reconstruction process, they will be forgotten. When I was in Liberia, one of these girls literally hung on to me and said, “Please don’t forget me. I know they will forget me. Please, you don’t forget me!” I have been to many villages where girls would hold on to me feeling that I may be their only hope.

Putting their issues onto these peace tables are extremely critical. I was very pleased that Nelson Mandela understood it. He was the first one who got us together for the Arusha Process when he was mediating the Burundi peace process.

SG: Which of your many awards have the most meaning for you, and why?

Dr. Noeleen Heyzer meets with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi in Yangon. (June, 2011) Photo: Mr. Aye Win, UNIC in Yangon

Dr Heyzer: Dag Hammarskjöld was a Secretary-General of the United Nations that I deeply admired, a man of deep courage, principals and moral authority. I got the Hammarskjöld medal soon after I went to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where he was killed. I was negotiating some of the peace arrangements with women from the DRC. When I got back to New York, on my table was the announcement of this award. I was deeply touched.

The other award was from the United Nations’ NGO Committee on the Status of Women. Many in the women’s movements see me as belonging to them. It is a privilege to be able to open doors for them, and to use my UN position or my intergovernmental experiences to make sure that their issues are very much on the table, to invest in a constituency for change. I do not believe that any individual can sustain change or that any institution will be accountable for change without a strong constituency.

SG: It is often said that politics rules the world and the boardroom. How can individuals make a difference?

Dr Heyzer: Politics is about power. One needs to know what power is and how to use it. For me, it is very simple. I know I have power because of my position, personality, alliances, because I have accumulated certain knowledge, and am educated. The issue is what you do with power. You can use power over people to dominate them, or you can use power with people to harness, build and mobilise alliances for good. I also believe very strongly in power within. I spend time building my spiritual and internal strength. At the end of the day, you need to undergo a deep internal transformation to be an authentic, accountable and credible leader.

SG: What does it mean to be a good global citizen?

Dr Heyzer: It is about human solidarity. We live in such an interdependent, interrelated world, where decisions taken somewhere in the world can affect all of us. Just look at the financial crisis. It started with a few decision makers in the financial sector, but affected all of us. Look at September 11th.

Some crazy extremists make a decision somewhere and it affected the most powerful capital city and the rest of the world. Because we live on one planet, the only home we have, it also means solidarity in our responsibility to take care of Mother Earth and her ecological systems that support life and give us so much. We cannot take the gifts of the earth for granted.

Secondly, there are disparities in the world.

If we don’t try to create a better world that is fit for all, there will be grievances and transnational crimes that affect all of us. If we do not know how to resolve conflicts, the arms industry will keep growing. Instead of investing in the growth of development to build richer human lives, we will be feeding the industry of destruction. I have seen the best and the worst. Human beings are capable of so much, and somehow we need to provide the environment or inspiration to bring out the best in all of us.”

SG: Which of your many awards have the most meaning for you, and why?

Dr Heyzer: Dag Hammarskjöld was a Secretary-General of the United Nations that I deeply admired, a man of deep courage, principals and moral authority. I got the Hammarskjöld medal soon after I went to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where he was killed. I was negotiating some of the peace arrangements with women from the DRC. When I got back to New York, on my table was the announcement of this award. I was deeply touched.

The other award was from the United Nations’ NGO Committee on the Status of Women. Many in the women’s movements see me as belonging to them. It is a privilege to be able to open doors for them, and to use my UN position or my intergovernmental experiences to make sure that their issues are very much on the table, to invest in a constituency for change. I do not believe that any individual can sustain change or that any institution will be accountable for change without a strong constituency.

SG: It is often said that politics rules the world and the boardroom. How can individuals make a difference?

Dr Heyzer: Politics is about power. One needs to know what power is and how to use it. For me, it is very simple. I know I have power because of my position, personality, alliances, because I have accumulated certain knowledge, and am educated. The issue is what you do with power.

You can use power over people to dominate them, or you can use power with people to harness, build and mobilise alliances for good.

I also believe very strongly in power within. I spend time building my spiritual and internal strength. At the end of the day, you need to undergo a deep internal ransformation to be an authentic, accountable and credible leader.

SG: What does it mean to be a good global citizen?

Dr Heyzer: It is about human solidarity. We live in such an interdependent, interrelated world, where decisions taken somewhere in the world can affect all of us. Just look at the financial crisis. It started with a few decision makers in the financial sector, but affected all of us. Look at September 11th.

Some crazy extremists make a decision somewhere and it affected the most powerful capital city and the rest of the world. Because we live on one planet, the only home we have, it also means solidarity in our responsibility to take care of Mother Earth and her ecological systems that support life and give us so much. We cannot take the gifts of the earth for granted.

Secondly, there are disparities in the world. If we don’t try to create a better world that is fit for all, there will be grievances and transnational crimes that affect all of us. If we do not know how to resolve conflicts, the arms industry will keep growing. Instead of investing in the growth of development to build richer human lives, we will be feeding the industry of destruction. I have seen the best and the worst. Human beings are capable of so much, and somehow we need to provide the environment or inspiration to bring out the best in all of us.

SG: Is Singapore a trailblazer or a thought-leader? And where do you see Singaporeans as responsible global citizens?

Dr Heyzer: Singapore is a leader through its sheer determination that the small can be big. It has turned its smallness into an advantage. Singapore has succeeded because it has invested in quality education and healthcare, and done very well in affordable housing for the working poor, in public transportation, and sustainable urbanisation — creating new standards for liveable cities.

I feel that Singapore is never satisfied with itself, so it is always looking for the next frontier. It has shifted from being an entrepot to a labour-intensive industry, to a capital-intensive industry, a service industry, a financial hub, a knowledge-centre…and from being a Garden City to being a City in a Garden.

As for Singaporeans, some are socially engaged, but many are struggling to be more financially secure. Singapore has the largest number of millionaires, and many are foreigners. We need to ensure that our growth strategies are more inclusive and assets more fairly shared. Singaporeans have also travelled widely, and are more exposed through media to other possibilities. They want greater personal freedoms and a bigger role in shaping their own as well as the country’s and the region’s future.

SG: Are there any unique Singaporean values, and is there enough being done for the next generation?

Dr Heyzer: I am not sure if there are unique Singaporean values. There are so many different types of Singaporean values. I can tell you the values that I grew up with and inherited from my family in Singapore. One critical value was to…

invest in the next generation and to never take more than you need. There should be a maximum level of living to give us dignity and security. It’s about having a sense of shared responsibility across generations.

We can do away with much material greed, and search for better quality growth, whilst redefining the meaning of “the good life”.

Singapore is a good example worldwide for sustainable urbanisation. There is strong emphasis on water management, and keeping the city clean. I love the green in the city and how the environment is being managed. There is still a lot that can be done with energy efficiency and usage. Singapore is ahead of the curve in using technology and innovations for sustainability. However, I don’t think there is enough social entrepreneurship and innovation to address social equity issues, although the government has invested in supporting low-income families. There is a “sandwich population” that is ignored, people that are too rich to qualify for public housing, but too poor to own private housing. Singapore needs to manage the inflow of capital to avoid creating asset bubbles that make it difficult for this population. Some of their grievances are already taking a political form.

SG: What would you say lies at the heart of Singapore and where does its future lie?

Dr Heyzer: Singapore’s heartbeat is its constant rhythm of regenerating itself. I like its openness to learning and bringing in good practices. For example, Singapore didn’t have an orchestra, but they had no problems bringing in some of the best musicians from Eastern Europe into the country. This ability to learn from others and for regeneration is critical, and so is the constant desire to improve itself. This capacity to invest in itself puts Singapore at the cutting edge. But it is still a red dot on the world map, and on the map of Asia. So it has to learn to work closely with its neighbours and be much more integrated in helping and sharing its experiences. Singapore should now be a bit more generous in contributing to the work to build a more trusted, prosperous and resilient neighbourhood.