Stories > The Pacesetter

The Pacesetter

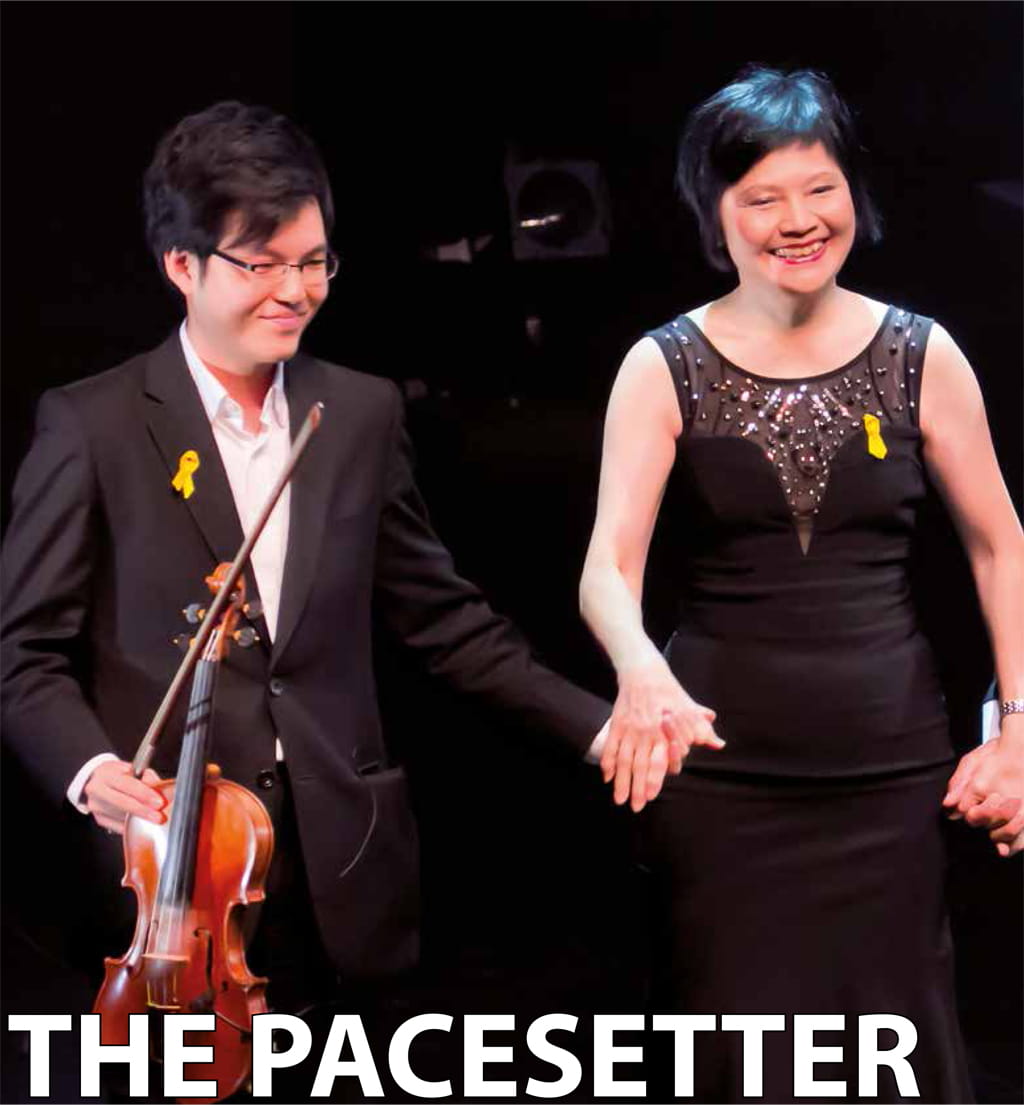

Lai Siu Chiu (centre) has been an active proponent of any fund-raising projects that benefit ex-offenders to help them reintegrate into society and reduce the risk of recidivism.

Holding her own among men at a time when gender equality was a novelty in the work force, Singapore’s first female Supreme Court Judge has now retired. Lai Siu Chiu has replaced ‘Justice’ from her appellation with ‘Ms’, but continues to focus on the practical and necessary in her quest to continue serving.

By Kim Lee

ai Siu Chiu, fresh into retirement after 40 years in law, isn’t the sort affected by praise and puffery. She dismisses being called a trailblazer for women in the judiciary, reminding that: “It was the press, not I, that described me as a trailblazer. I prefer to consider myself a pacesetter.”

Unlike other female practitioners at the Bar in the 1980s, Lai was not a conveyancer or corporate lawyer, but a litigator — a rarity then. She led the way for Justices Judith Prakash and Belinda Ang to follow on the Supreme Court Bench.

Lai wanted to be treated as an equal to the men she worked with, and believes she was. That possibly lent weight to the then Chief Justice Yong Pung How appointing her to the High Court Bench, a radical step for women then, in May 1991, to which she modestly says, “I happened to be in the right place at the right time.”

Lai marked her retirement with a move into a new home, but she’s not calling it a day yet. “Law is in my blood. I have lived and breathed law for over 40 years; I enjoy the practice of law; I am not giving it up just because I am retired from public service.”

SG: What have your years on the Bench been like?

Lai: Before my appointment, it took years for a case to come up for trial. However, once the Supreme Court addressed and overcame the backlog in the years shortly after CJ Yong’s appointment as Chief Justice in 1990, the problems were quickly resolved or largely reduced. As a judge, I only needed to focus my attention on the facts presented and decide on the merits of each case.

The quality of the Bar has also improved over the years. Lawyers in my court were getting increasingly better qualified and had improved advocacy skills, especially with the introduction of senior counsel appointments in January 1997. Women lawyers appeared in my court with increasing frequency. The quality of their presentations also improved. I found it exhilarating and enjoyable whenever I had a good counsel arguing a case before me.

The nature and types of cases tried in the High Court went from beyond ‘run of the mill’ contract or negligence actions; to increasingly more complex and sophisticated – disputes which required careful analysis and consideration. Being on the Bench was a continuous learning curve for me. One day, I would be hearing a dispute involving prawn farming. On another occasion, I would be dealing with a trademark infringement case. On yet another day, I would try a case where an ex-employee in the kitchen allegedly stole his former employer’s secret recipe. The variety of cases was almost limitless.

SG: What’s your involvement in charity work?

Lai: I support children’s charities because I feel that the young and the elderly are the most vulnerable. The young cannot speak up about their pain and trauma. The High Court had a case where a three-year-old girl was raped by her own father. Such a child could not even run away from the abuse, let alone fend for herself on the streets. The elderly are vulnerable because they are too weak or fragile to fend for themselves, but unlike the young, they are usually able to convey their feelings.

But my involvement in charity had nothing to do with being on the Bench. I was chairperson of the Children’s Charities Association (CCA) in the early 1980s. The CCA is an umbrella organisation for six children’s charities. It’s heart-breaking to see a child with cerebral palsy in the Spastics Association try so very hard to walk or even stand; an action most people take for granted. Many children under the care of Singapore Children’s Society (SCS) in the 1980s were ‘latchkey’ children who literally wore their house keys on a chain around their necks because their parents were not in when they returned home from school. The parents either needed to work full-time because of financial constraints or they were ill and could not take care of themselves, let alone their children. Sometimes children were not fed properly or at all. SCS provided a substitute home for such children, like the one I remember at Henderson Road, where the children could do their homework and have meals.

I stepped down from the CCA after my first child was born in 1984 and decided to passively support the Salvation Army’s Gracehaven Home at Choa Chu Kang to donate toys, and/or clothes.

My support for the Yellow Ribbon Fund (YRF) and The Singapore After Care Association came much later when I was appointed the Chairperson of the Membership and Social committee of the Singapore Academy of Law (SAL) in August 2006. The administration of criminal justice has three aspects: Punishment; Deterrence; and Rehabilitation. The YRF comes under the third aspect of criminal justice. The YRF helps ex-offenders and their families reintegrate into society. If these people are not rehabilitated and given a second chance in life, there is a high likelihood of their recidivism. Surely, our courts should set an example and the pace by supporting the YRF.

Hence, it was decided by my committee and I last year that it would benefit SAL’s 25th anniversary to support the YRF on a long-term basis, rather than to choose a different charity to support every year. SAL succeeded in raising more than $303,000 for the YRF and in instilling a greater awareness in the public of YRF’s existence and cause.

SG: Why do you make time for charity work?

Lai: As Singapore moves from the Third World to the First, we must never forget the hardships our older generations endured in the early years post-independence. Neither should we be complacent and take our current prosperity for granted, bearing in mind we are but a little red dot on the map. We should also not forget the less fortunate and less well-off amongst us for whom daily life is still a struggle. Trite as it may sound, those of us who have done well in life should give back to society. We should lend a helping hand to those who have no or not enough resources of their own, or who have fallen by the wayside. That is the true mark of an advanced and progressive society. We can afford to, and should, be a caring or more caring society now that Singapore has advanced into the First World. Singapore should not be seen as a country that pursues wealth and material things at the expense of other consideration.

Being charitable has its own rewards: I find it satisfying to be able to make a difference to other people’s lives.

Now retired, Lai reflects on how systems and processes in the judicial system have improved, in tandem with advancing advocacy skills and quality of presentations.

SG: What do you think of the Singapore judiciary?

Lai: From the time of CJ Yong, Singapore’s judiciary has been lauded as one of the most outstanding in the world in terms of efficiency, transparency and fairness. Many countries send their judiciary staff to learn from us — I discovered this from other delegates mainly from Africa, while attending a Commonwealth Law Conference in Uganda in 2012. Our courts no longer have a backlog and we set key performance indices for ourselves as a benchmark to maintain our standards. Both the Supreme Court and the Subordinate/State Courts are constantly looking for ways to improve their efficiency, service to the public, and productivity.

SG: Are women judges different from their male counterparts?

Lai: I don’t think I or the other lady judges decide cases any differently from our male colleagues. However, in determining ancillary matters like maintenance post-divorce, I suppose the ladies on the Bench have a better appreciation of the cost of living and the cost of necessities and nonessentials items. I once asked a male colleague if he knew the cost of a brand of lipstick versus that of another brand. He acknowledged he did not. Hence, the courts adopt a ‘broad brush approach’ when it comes to determining the quantum of maintenance to be awarded to a claimant.

SG: You have reputation for a high work ethic. How did you get it?

Lai: I live by the principle that either I do a task well or not at all. From young, I have been self-disciplined especially in my studies. I knew I had to familiarise myself with a case before I go into the court-room. Otherwise, my conscience won’t give me a moment’s peace. So I would read my files beforehand, sometimes at the expense of sleep or leisure activities or an outing. I would get annoyed at lawyers who came to court unprepared because there was even more reason for them to be ready for trial than me, as they owed it to their clients (who paid their fees). The lackadaisical attitude of some lawyers was shocking; I often wondered how they could answer to their clients if they lost a case because of lack of preparation. If their lack of preparation was very obvious, I would sometimes rebuke them (in the absence of their clients), pointing out that as officers of the court, they had failed in their duties to their clients as well as to the court.

Lai singing at the Singapore Academy of Law’s Yellow Ribbon Fundraiser; a cause that she has championed throughout her career

SG: Looking back, what is your take on your career?

Lai: Sometimes I agonised over making a difficult decision, but I never encountered any challenge that I considered insurmountable.

I am surprised that someone who initially came from Malacca to Singapore to study law has come so far. Never in my wildest dreams would I have imagined this was how my life would pan out.

My time on the Bench has also been a humbling experience; I have seen that life can be unpredictable. A person can be at the zenith of his career, power or wealth one day, only to lose it all on another day through a cruel twist of fate, misjudgment or misfortune. One cannot take life for granted.

SG: How did you come to sing at the 25th Anniversary of the Singapore Academy of Law Yellow Ribbon fundraiser?

Lai: I used to sing in my campus days because I had friends from the Raffles Hall hostel who played the guitar and sang folk songs a la Simon & Garfunkel, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joni Mitchell, etc, and I used to join them. I sang at SAL’s concert on 12 Sep 2013 because my committee organised the concert and I felt I should perform myself before I asked others to do so. I used to play the piano in my younger days and have a good ear for music.

SG: What do you think is the greatest injustice in our society?

Lai: The widening gap between the rich and the poor.

SG: How would you say life has changed regarding the greatest challenges for the generation of Singaporeans now on the cusp of adulthood?

Lai: Life is far more complicated and fast-paced than in the time of our forefathers and when I was in private practice. For the average and many persons, there is far more pressure in working to succeed in life; conversely, there is less leisure for the average person while macroeconomics in this Internet era mean that events in other countries invariably have an impact or a greater impact on Singapore. I think Singaporeans need to cultivate resilience, fortitude in the face of adversities, maintain a strong sense of survivorship, and a hunger to succeed in order to thrive in these times.