Leading Singapore ceramicist and national icon, Iskandar Jalil, envisions a culture of pottery where the craft is a seamless part of daily life.

Leading Singapore ceramicist and national icon, Iskandar Jalil, envisions a culture of pottery where the craft is a seamless part of daily life.

By Ming Rodrigues

Gentle, encouraging whistles penetrate the searing afternoon heat like a soothing salve. “Come, come and eat…,” the spry man coaxes, carefully laying birdseed in small dishes on the floor. At this signal, a small flock of doves flutters down for the offering, unafraid — and Iskandar Jalil’s weather-beaten face breaks into a huge smile.

“We welcome everyone at Temasek Potters, even birds!” quips the 72-year-old, referring to his new studio and teaching centre on the edge of Temasek Polytechnic in Tampines, Singapore. The studio is a collective set up for and run by artists and volunteers.

Iskandar’s “open-arms, open-door” policy is no surprise. As Singapore’s best-known ceramicist, a national visual arts icon and cultural educator, the man’s fidelity to bringing pottery to the larger community is well documented. As Singapore sought to position itself as an arts hub, Iskandar championed a ceramics culture, constantly pushing the notion of pottery beyond that of a niche craft to one worthy of being woven into the very fabric of society. Iskandar explains: “There needs to be a culture where we live and breathe pottery, where it is part of our lives; for example, books on pottery should be readily available, funding and support of pottery schools and communities, exhibitions and programmes should be strong, and so, too, the demand for ceramics.”

Essentially, a pottery culture can only take root when people understand ceramics’ integral role in a society; how it not only reflects the function it was created for, but is an art in its own right and a repository of a people and history. For example, forms of vessels and decorations show artistic perspectives and styles and the way of life at a point in time. From vessels to eat and drink from, multi-purpose containers or receptacles that transport water, to those that hold the remains of loved ones — for thousands of years people have relied on potters and their trade, and pottery was a natural extension of livelihoods.

It could take several generations before pottery ever gets ingrained in Singapore’s cultural blueprint and daily life, but Iskandar set that machine in motion years ago.

Shaped by the Clay

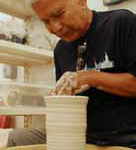

- Master Potter Iskandar Jalil commands steady hands at the wheel

Ironically, Iskandar’s origins were not in ceramics. Born in 1940 in Singapore, he grew up in Kampong Chantek in Bukit Timah, studied at Victoria School and after graduating from Teachers Training College (TTC) in 1962, became a mathematics and science teacher. But as destiny would have it, during his time in TTC he tried his hand at a pottery class and discovered an affinity for clay that would drive his life in an unexpected direction and eventually make the art world sit up. In 1972, on a Colombo Plan Scholarship, Iskandar left for Tajimi in Japan’s Gifu prefecture, the epicenter of Japan’s pottery culture. The experience forever changed his outlook on life and his work ethic. Among his ruminations in the book Material Message Metaphor, The Pottery Voice of Iskandar Jalil, he talks reverently about the Japanese respect for the value of “truth to material”, working without pretensions, the freedom offered by simplicity and respect for the anonymous crafts person. “My interaction with the Japanese potters sharpened my skills. Interacting with their work, philosophy, work attitude and commitment, I was inspired by them,” he says.

This revelatory sojourn sealed his passionate commitment to the art. Over the decades, Iskandar’s works have been exhibited in Malaysia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, and Sweden. They are much sought after and held in many public and private collections, from the National Museum of Sweden to the National Museum of Singapore, to collections belonging to the Sultan of Brunei, former US President George Bush and Singapore’s former Minister Mentor Lee Kuan Yew. In 1988, he was awarded the Cultural Medallion for Visual Arts, Singapore’s highest honour recognising individuals who have made distinctive contributions in shaping Singapore’s cultural landscape. Besides being a prolific potter, he also influenced many a young artist by teaching and sharing his love for ceramics at the Baharuddin Vocational Institute, which started in 1969 running courses from graphic design to dressmaking, primarily to service the design and tourism industry. In 1990, with the inception of Temasek Polytechnic, the institute was absorbed into the Polytechnic’s School of Design. Iskandar then taught at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, and later returned to Temasek Polytechnic School of Design. He retired in 1999 at the age of 59. Still, that hasn’t stopped him from continuing to learn, teach and create.

More recently, his Jalan Bahar Clay Studio, officially launched in November 2006, was another pitch for a pottery culture — it holds Singapore’s largest and oldest dragon kiln, one of only two such kilns left here. By 1985, due to rapid developments in residential and industrial facilities coupled with a drop in demand for ceramic ware, many family-owned ceramic businesses were forced to shut down. The only other surviving dragon kiln has ceased operations and moved away from ceramic production. Chinese in origin, the long and undulating kiln is riddled with stoking holes, lending it the appearance of a dragon when it is fired and smoke curls out of the holes. For his raw materials, Iskandar has long used local and regional clay in his works, sourcing his raw material from slopes, abandoned construction sites, and even graveyards years before ecoconsciousness and going local came into vogue.

Following the Flow

Decades later, his approach to the art remains simple:

“Follow nature. Don’t fight the clay, let it work for you, otherwise you will struggle and produce poor work.”

This advice comes from a man with near legendary intolerance for incompetence. He has been known to take a hammer to his students’ work if he deems it substandard, earning himself the nickname “The Flying Missile”.

For Iskandar, there is no short cut to making the grade. After 40 illustrious years in ceramics, it was only in 2000 that he was bestowed the title of Master Potter by his Japanese pottery mentor and sensei. “It takes 20–30 years to be a Master Potter, it’s a long journey,” says Iskandar, who had returned to Japan to visit his old teacher to explore his renewed interest in the ceramic bowl form. In part to acknowledge the “full circle” of his career, his teacher conferred the title on him.

As a mentor to Singapore’s next generation of potters, Iskandar insists his students study and get hands-on experience in Eastern and Western methodology. “You need to know both before you can

be a teacher.” For example, Asians tend to use their hands as tools while Western potters rely on analysis and technology. “I ask them to familiarise themselves with the machinery, tools, wheels, clay of both cultures…. You must be versatile not just to be a good potter, but a mentor,” he says, casting his eye beyond the next generation of potters.

Beyond the Ego

He is deeply concerned about how the foundation he has laid for ceramic art in Singapore will be built upon. “I worry for the next generation,” he admits, alluding to his dismay at the mindset of today’s time-starved generation fed on instant gratification. “They like to do everything fast. They put creativity and expression above all else, complain about the limitations of clay, and are not willing to work hard — it’s all about the ego and individual recognition,” he opines. To be a good potter, one must “be disciplined, and learn the fundamental skills and techniques of craftsmanship. Creativity is accidental, it will come later,” he explains. Despite the hard work and rigours demanded by the art, it hasn’t deterred a surprising number of new students — young 30- to 40-somethings — who have been streaming into Temasek Potters to learn the craft. Fees are low and students can work the whole day. The process is organic, with Iskandar teaching and demonstrating as he goes along. “I always bring them back to the fundamental question:

‘How do you feel about your work, does it strike a chord in you, in your soul?’”

Very quickly, he is able to sift the students “with heart” from those without. Iskandar believes that good pottery stems from pure instinct. “Good art work comes without much thought, concept and intellect.”

The Next Wave

Despite his concern over the quick-fix mentality of today’s generation, all is not lost with local talent. Over the decades, Iskandar has seen a few of his students carve their niche in the art. Some teach pottery at community centres in Tanjong Pagar and Bishan, at Tampines Pottery Club, as well as Jalan Bahar Clay Studios. One former student, Tat Yan Soo, now runs pottery factories in Indonesia and shares his skill and knowledge with villagers.

Those who have made a name for themselves include Ahmad Bakar, who took lessons from Iskandar at LaSalle College of Fine Arts in 1989, and went on to lecture at LaSalle SIA College of Fine Arts. Exhibitions of his work got him noticed and he was commissioned to create 25 sculptural ceramics for APEC 2009 Singapore. Senior Lecturer in the Department of Malay Studies at the National University of Singapore (NUS), Dr Suriani Suratnam, first took pottery classes at the Centre for the Arts at NUS in 2001 under Iskandar’s tutelage. She has gone on to receive commissions for Sentosa Resort and Spa, the National Heritage Board and Temasek Holdings.

All Together Now

The year 2013 looks to be significant for the local pottery community on several levels. On January 18, the Japan Creative Centre will hold an exhibition featuring the works of Iskandar, his protégés and students. “It’s a chance for people to see what I’ve taught through the years and showcase the diversity of their art, which includes artistic, sculptural and functional pieces.”

Then there is the ambitious plan to convert part of his terraced house in Kembangan into a ceramics museum. It will be open to the public and include a retail section for his students’ works. The task of sorting through and cataloguing up to 800 pieces of his original pottery pieces, personal travel journals, pictures and videos, assorted pottery books and magazines is a mammoth one. “I don’t know how long it will take to complete but I hope to leave something behind to help people understand and appreciate pottery.”

For all his achievements, Iskandar prefers to be seen as a craftsman and teacher, not a cultural icon. “I am happy that I managed to raise pottery to a national level and for it to be recognised as an art. From here, I am confident my students — and their students — will continue to sow and nurture a pottery culture we can be proud of.”