Stories > The Power Of Knowledge

The Power Of Knowledge

A learning centre in Indonesia run by refugees and volunteers brings new hope to the displaced community.

BY TAN KENG YAO

hen he was only 15, Afghan Abdullah Sarwari fled Pakistan, where he was born, for Indonesia with his mother and four siblings. His family belonged to the Hazara ethnic minority group, so they were targeted by extremists in their home city of Quetta, who regularly killed members of the Hazara tribe. His parents had fled from Afghanistan to Pakistan before he was born.

The family arrived in Cisarua, a small town south of Jakarta that has become a hub for refugees from the Middle East and Africa, seeking a better life and hoping to end their quest in Australia. However, refugees like them often have to grapple with a complex set of challenges before gaining permanent resettlement elsewhere.

“You Can’t Help Others If You Don’t Help Yourself First. I Feel Responsible For The Refugees And I Will Do Whatever It Takes To Raise Awareness On Their Behalf,” Says Abdullah Sarwari.

Abdullah and his family are not allowed to work or study in Indonesia based on local laws, which leaves them worrying about money as well as professional development opportunities. It also keeps them at loose ends, not knowing what to do with themselves.

The refugees’ only chance is to be resettled in a third country, which can be a lengthy process. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), during the first six months of 2017, only 322 refugees out of over 14,000 in Indonesia were resettled to a third country. The long-drawn resettlement process could take up to 25 years – or more. Returning to their home country is not an option for the refugees either, which leaves them caught in the middle. Stuck in an uncertain situation, many lose hope.

Having co-founded Refugee Learning Centre, Abdullah also took on the role of the school’s principal

FINDING HOPE IN EDUCATION

Abdullah found life very tough during his first six months in Indonesia. “I had left everything behind and was depressed and hopeless as a teenager stuck at home all day. But rather than curse the darkness, I decided to light a candle,” he says.

In 2015, he and a group of fellow refugees came together and started thinking about how they could do something for themselves instead of waiting for someone from outside the camp to help.

“After three to four weeks of holding meetings in a park, we finally decided that seeking education is not a crime, and no one can penalise us for trying to do something positive while being in limbo. So we joined hands and established Refugee Learning Centre [RLC] with the aim of providing education to refugee children.”

He and his friends hammered out their ideas, working out everything from the members of management to teachers, logistics and funds, and how to run a sustainable operation. Finally, they chose five members of the community who took on different roles, and also six female refugees who would teach the students.

They found a location for the school, and the parents of their first 25 students agreed to pay the first three months of rent for the building that would house the school. They did by dipping into their savings since they do not have any source of income.

“We figured that in these three months, we will try to find an organisation to help and support our school,” he says. It was very hard in the first year for RLC because of challenges such as looking for a funding source, a lack of experience in running a community-based centre, and young teachers who have never taught before.

Fortunately, after the first three months, the founders managed to get in touch with Same Skies, a non-profit organisation that supports refugees and asylum seekers.

Same Skies agreed to pay the rent for the next six months and, at the same time, train the management team to run the school properly, create a website and a Facebook page, do online fund-raising, and conduct workshops to train RLC’s teachers.

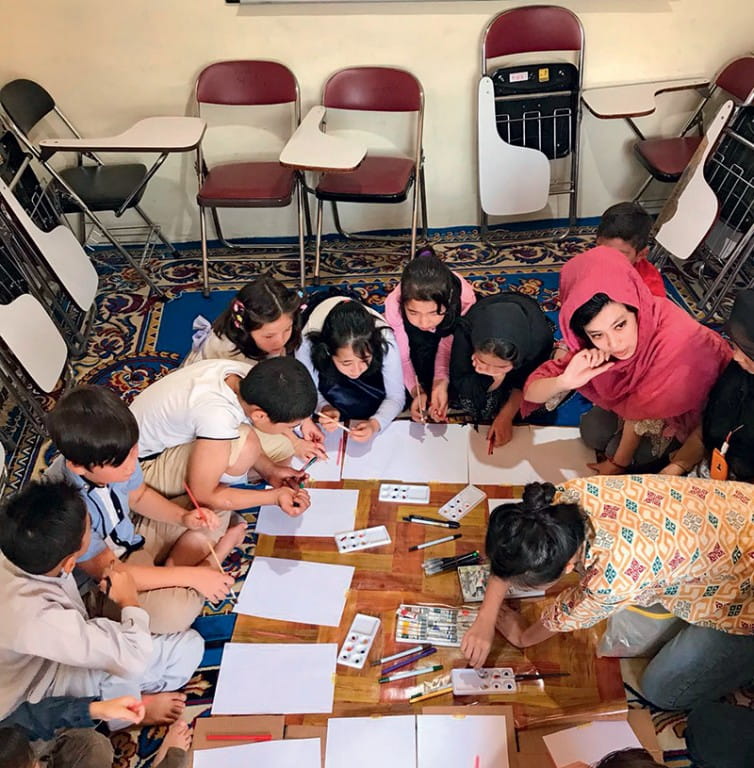

Abdullah Sarwari (first row, second from left) galvanised support from the refugee community and other non-profit organisations to start an informal school for the former in Cisarua, Indonesia.

“This first step really helped the team understand our work better and, since then, we have been learning as we go,” he recalls. “The important thing is we never lost sight of our main goal, which is providing basic education to those who do not have access to it.”

Abdullah took on the role of principal at RLC, where he oversaw operations and managed the day-to-day running of the school. He also took charge of communications and raising funds for the school’s rent and operational expenses.

CREATING A COMMUNITY

When RLC was set up, its primary goal was to provide basic education to refugee children, but it has since grown to teach more than 180 children and about 100 adults. It is run by unpaid volunteers and its expenses are solely funded from donations.

It is also trying to bring the community closer and relieve their stress by organising social activities such as concerts and opportunities to play sports, especially for the women, who would not have had the chance to do so in their home countries.

RLC also has volunteers from outside the community to run workshops and classes, such as Mahardhika Sadjad, an Indonesian PhD researcher at the International Institute of Social Studies in the Netherlands.

He conducted English classes for adult students to help them prepare for General Educational Development English tests. This would allow refugees the chance to obtain certification for high school-level academic skills that would be useful for when they get resettled. The academic volunteer also taught a geography class to young children at RLC.

Another volunteer is Lim Nan, a Singaporean lecturer from SIM-Global Education. Together with his nephew, they have been running chess workshops for the refugees.

The school conducts English classes for adult students to help them prepare for high schoollevel academic certification that further helps in their resettlement process.

RESILIENCE IN THE FACE OF CHALLENGES

Despite the very trying circumstances the refugees find themselves in, the volunteers found their spirit admirable. “They are a very resilient group of people who are making the best in extremely difficult circumstances,” says Lim. “They are receptive to new ideas, and are very welcoming.”

Maharadhika concurs: “One thing that really struck me was the resilience that they displayed in building their own support communities in Cisarua. The learning centres were always buzzing with activities to help them cope with the challenges they faced.

“I consider many of the refugees I taught as friends, and these relationships naturally gave me a much more nuanced understanding of their situation. I will forever be grateful to them for allowing me to be a part of their community.”

“The Refugees Are A Very Resilient Group Of People Who Are Making The Best In Extremely Difficult Circumstances. They Are Receptive To New Ideas, And Are Very Welcoming.”

Lim Nan, Singaporean Volunteer And Academic

BUILDING NEW BRIDGES

Before RLC was set up, the refugees did not interact much with the Indonesians because of language barriers. On top of that, the locals often mistook the refugees for Arab tourists from the Middle East, who often visited Puncak in Cisarua.

“So the prices were always double or triple for us,” quips Abdullah. But as more refugees picked up Bahasa Indonesia through classes at RLC, they were able to communicate with the locals, introducing themselves, and explaining who they are and where they come from – a move well received by the Indonesians.

“I personally admire the patience and calm nature of the Indonesians. It is something that I have tried to practise in my own life as well,” he shares.

A video story about RLC’s work was featured on Singapore International Foundation’s digital storytelling portal, Our Better World, which provided much-needed exposure to its work. After the video was featured – it was viewed almost 900,000 times and received over 11,000 likes and shares on Facebook – the non-profit received enquiries from over 100 volunteers who were interested to work and collaborate with RLC in the future in different areas. At that time, RLC was also running its fund-raising campaign and noticed a rise in donations.

Among the many volunteer tutors, the school counts several Indonesians and Singaporeans.

“OBW’s storytelling has definitely exposed us to a wider audience, and we really do appreciate their help and support,” says Abdullah.

STARTING A NEW LIFE

RLC has changed the lives of the refugees, a fact exemplified by Abdullah. “After cofounding RLC and working with an amazing team for the past four years, it has truly been a life-changing experience for me,” he says.

And life has begun to look up for the 21-year-old, who was offered a job as an interpreter and translator with UNHCR in April 2019, selected out of 300 refugee applicants. In October 2019, he shared his story at a TedX Ubud talk. Since then, he and his family have been resettled in Canada – a process that took a few years to come to fruition. Prior to leaving for Canada, he had to step down as the principal of RLC – a move he describes as being particularly hard on him.

“RLC is like a child to me. I was there when it was born and I have seen it grow and get bigger every day,” he says. While he still acts as an adviser to the team, his plan, first and foremost, is to enrol in university and continue his education.

He says: “I am lagging behind in my personal goals, and it would be great to catch up and learn and improve as a person for a while. After all, you can’t help others if you don’t help yourself first.

“I will try my best to continue my volunteer work while undertaking higher studies. I know it will be hard to balance both but I think it would be worth it. I feel responsible for them and I will do whatever it takes to raise awareness on their behalf.”

PLIGHT OF THE DISPLACED COMMUNITIES

|

||||

26 millionrefugees have been displaced from their homes, over half of whom are under the age of 18. |

20.4 millionrefugees are accounted for under UNHCR’s mandate. |

|||

5.5 millionPalestinian refugees scattered mainly in Lebanon, Jordan and Syria, come under the mandate of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East. |

68%of UNHCR refugees come from five countries: Syria (6.6 million), Afghanistan (2.7 million), South Sudan (2.2 million), Myanmar (1.1 million) and Venezuela (3.7 million). |

|||

107,800refugees have been resettled in 26 countries. |

Source: www.unhcr.org/ figures-at-a-glance.html | |||

Scan the QR code or visit

www.ourbetterworld.org/story/aschool-

for-refugees-by-refugees

to find out more.