Stories > The Roving Clinic

The Roving Clinic

Singaporean and Cambodian medical students bond to empower impoverished communities living in rural Cambodia with proper healthcare.

BY SOL E SOLOMON

ursat, the fourth largest province in Cambodia, is one of the country’s poorest and most underdeveloped.

Here, proper healthcare facilities, along with electricity and proper plumbing, are inaccessible to those in rural communities.

Recognising the lack of properly trained medical professionals in the region, students of National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine), supported by the NUS Medical Society, started Project Lokun (which means doctor in the Hokkien dialect) in 2006.

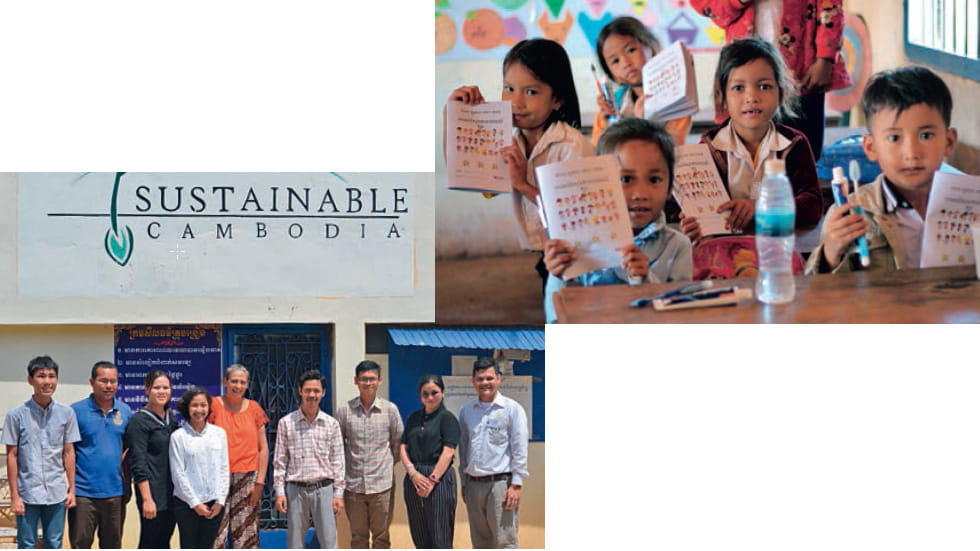

From Left: Project Lokun sees medical students making twice yearly trips to Pursat, Cambodia to provide villagers with medical aid as well as education on good health practices.

This project sees students embarking on biannual humanitarian missions to the province to provide medical aid to villagers, along with education on good health practices.

Thirteen years and 24 editions on, Project Lokun has helped over 9,000 patients from more than five villages.

“People in the province tend to prioritise work and family over their health. They often avoid visiting doctors until their conditions worsen,” shares Liu Biquan, who was the director of the 10th and 12th editions of Project Lokun, and now volunteers on the trips as a medical doctor.

In making healthcare accessible to the villagers of Pursat, Project Lokun’s volunteers conduct free clinics to treat and diagnose them. As systemic hygiene issues can cause communicable diseases to spread easily in the community, the volunteers teach locals good oral hygiene habits, proper water sanitation and ways to identify disease symptoms, as well as disease prevention.

“Thirteen Years And 24 Editions On, Project Lokun Has Helped Over 9,000 Patients From More Than Five Villages.”

CARE WITHIN CONTEXT

In line with the project’s vision of continuity, each student makes three consecutive trips, each of which is accompanied by a team of Singaporean doctors, as well as volunteer Cambodian healthcare professionals. For the revolving teams of medical students who have volunteered in Cambodia, adjusting to a whole new approach to life and work in a developing country has not been without its difficulties, given the differences in culture.

However, with the help of its local partners, including NGO Sustainable Cambodia and the University of Puthisastra (UP), a private Cambodian institution in Phnom Penh, the Singapore team managed to bridge the language and cultural barriers.

“With UPPC, We're More Than Co-workers; We're Friends Working On This Together.”

Caitlin O'Hara, A Student Of NUS Medicine

Working with limited resources was also something the teams had to overcome.

“I think the greatest takeaway from the experience was the importance of listening to people with an open mind,” wrote Jessica Ng, a former student of NUS Medicine who was on the 12th Lokun trip in 2012, in her trip reflection piece.

From aid to education, Project Lokun has so far helped over 3,000 patients from more than five villages.

“After speaking with our translators and teachers at the schools, we realised that some parts of our health curriculum were not applicable to them. Things that we take for granted – like refrigerators, a proper market and running water – they do not have.”

To adhere to local norms, the Singapore wing of Project Lokun closely plans each trip with students from UP, who form the UP Planning Committee (UPPC). Their task is to lay the groundwork and seek permission from village heads to hold the clinics, while procuring local sponsors and producing education materials in Khmer.

Overall, the partnership increases efficiency, and ensures materials and initiatives are culturally appropriate.

For the Singapore team, collaborating closely with their Cambodian counterparts has given them invaluable insights into the local community.

Among them is Caitlin O’Hara, a student of NUS Medicine who was project director on the 23rd and 24th Lokun trips held in May and December 2018 respectively.

She recalls discovering that a lesson on nutrition she had prepared was not suitable for the Cambodians, who required more carbohydrate for their farm work.

“To make the lesson relevant, I relied on my friends from UP to help me tailor the plans to the Cambodians,” she shares.

The Singapore team was impressed by the proactive attitude of the Cambodian students, who swiftly reacted to issues. “Noticing that their fellow volunteers were tired out from repeating musculoskeletal stretching lessons, the UP students produced a video in their own language to teach the locals who handle labour-intensive jobs how to deal with their back and muscle aches,” explains O’Hara.

Similarly, the Cambodian undergraduates have also benefitted from the partnership. “Nobody’s opinion was left unheard, and we cooperated seamlessly as a team.

Working with the Singaporean doctors and seeing how they performed physical examinations with such precision was enlightening. Not only were they bright but also humble and easy to talk to,” shares Phalkun Roth, a UPPC leader.

Left to Right: By working hand-in-hand with local NGOs, Project Lokun ensures that its initiatives are culturally appropriate; Project Lokun volunteers provide schools with a health curriculum.

IN FOR THE LONG HAUL

Though Project Lokun team members shared their difficulties in quantifying the project’s success, there are signs that their joint efforts with UPPC are paying off.

A primary school, for instance, had announced plans to fix its water supply for kids to wash their hands, not long after the Lokuners, as project volunteers are affectionately known, had recommended an improved hygiene system.

The Singapore team was also pleased to discover that the schools they worked with are carrying out their lessons on a regular basis. In addition, Roth shares that he noticed one of the villagers had obtained a water filter and adopted the habit of boiling water, having been educated by the team.

Ultimately, the Lokuners aim to pass the responsibility of healthcare back to the local community. Dr Liu asserts that the partnership with UP students and NGOs helps to ensure that their efforts have long-term impact.

“Logistically, it is difficult for us to maintain a constant presence in the village, which is essential to improve healthcare provision and to encourage the referral of patients with more chronic or complex conditions back to their local healthcare system,” he says.

“We are attempting to mitigate this by inspiring local medical students to come back to serve this community when they graduate.” This, they hope to achieve by sharing skills with UPPC, such as on public health and data collection and analysis.

O’Hara says: “With UPPC, we are more than co-workers; we’re friends working on this together.”