For all its colour and auditory flamboyance, traditional Chinese opera was fading towards silent obscurity in Singapore in the late ‘70s. Today, it is enjoying a new vibrancy, and an appreciation that has grown beyond Singapore’s Chinese-speaking community.

For all its colour and auditory flamboyance, traditional Chinese opera was fading towards silent obscurity in Singapore in the late ‘70s. Today, it is enjoying a new vibrancy, and an appreciation that has grown beyond Singapore’s Chinese-speaking community.

By Swapna Mitter

You could say it was a rescue mission. If people spoke about traditional Chinese opera at all in the late ‘70s, it was to mourn its imminent death after 200 years in Singapore.

In spite of the highest levels of government intervention through late Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong, the then Ministry of Culture, and tourism initiatives like Opera at Hong Lim Park, the number of Chinese opera theatre groups had dwindled to less than 20 by the 1990s. It was hard to find a performance where once weekends in neighbourhoods resounded with their drama and music.

But two men played instrumental roles in reversing its fortunes. In the early 1990s, Prof Tommy Koh, then Singapore’s Ambassador to the US, approached Singapore’s doyen of Chinese opera, Dr Chua Soo Pong, to revive the art form.

The idea of Singapore losing Chinese opera was unimaginable to Dr Chua, like losing a part of oneself. “It is part of our heritage, like Malay and Indian traditional performance,” he emphasises.

A Love Affair

Chinese Opera proponent Dr Chua Soo Pong, 63, has written over 30 operas and toured 17 countries, including Turkey, Iran, India, Indonesia and USA. He has written two bilingual comic books on Chinese opera for children, and a series of books in Chinese on Hokkien, Cantonese and Teochew opera.

His love affair with the performing arts began as a little boy growing up in Jakarta where the fascinating world of theatre, music and dance in wayang kulit (shadow puppet theatre) and wayang wong (Javanese dance theatre) was a part of life. This love continued after he moved to Singapore at seven years old. Here, his grandmother brought him to Chinese operas at temple fairs. “These stories used to be enacted at different temples on different days…Grandma and I used to follow them.”

His childhood passion fired a lifetime of achievements in the Southeast Asian performance arts, particularly in Chinese opera, which he performs and writes, and made him one of the foremost names in this field. When the call from Prof Koh came, Dr Chua willingly gave up his position in Thailand as the first Senior Specialist at SEAMEO SPAFA, the Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts, an international body promoting cooperation in education, science and culture in Southeast Asia.

He was tasked to set up the Chinese Opera Institute (COI) in 1995, and run it as its founding director. “It was an honour to come back to serve, to do something with an art form that I deeply love.”

Attracting the Young

The idea was to revive Chinese opera in such a way that the youth could connect with it. Dr Chua’s first step was to gather principals from 13 schools to explain the COI’s intention to promote the art form by nurturing a new generation of audiences, not professional performers. There were few takers.

“We put in a lot of effort to convince the teachers, who may not have seen Chinese opera, of the value of exposing children to this because these stories promote all the correct values — filial piety, teamwork, patriotism — everything you need to teach children.” Among the first to add Chinese opera to their art education curricula were Nanyang Girls’ School, Bukit Panjang Secondary School and CHIJ Toh Payoh.

The students’ exposure to Chinese opera began with workshops with a few teachers the COI engaged from China. “It was really challenging at the beginning,” recalls Dr Chua. “These teachers were teaching professional full-time students from their own culture. We had to re-train them because they had no idea how to teach children who had no knowledge of Chinese opera. We had to create our own teaching materials.”

The school decided to give students one or two hours of Chinese opera per week over 10 weeks.

“We first taught them songs, then added some movements. More students gradually joined, attracted by the success of the initial groups of students, as well as the make-up and costumes.”

International Attention

Within two years, a Children’s Ensemble was formed. It gave its first full-length show — The Monkey King — at the end of 1999. It was a great success, and a springboard for another triumphant performance in Japan. After that, the group was booked, on the spot, to perform in Helsinki, Finland. To raise money for their travel expenses, the kids performed at Plaza Singapura, but they had to do it in English. “For these children aged between eight and 11 that was not a problem at all! They could change the dialogue into English with ease,” remembers Dr Chua.

Performing overseas gave these children exposure to international performers and audiences, and “when it is well received by the audience, especially one of a different culture, you feel you are also doing something for your country. There is a sense of pride in it. When the CHIJ girls went to Italy, they performed in the Rossini opera house, which is a really grand 300-year-old opera house. Some of these shows got standing ovations…that made all their hard work worth it. Many of these students come back to support our performances: they buy and help sell tickets — and these are not Chinese-educated kids!”

Multi-cultural Advantage

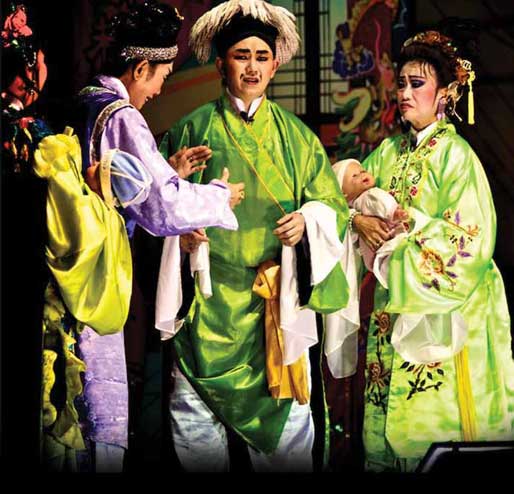

Dr Chua believes that the nation’s multi-cultural ethos is another advantage for Chinese opera. The cast is often multi-racial — Chinese, Malays, Indians and even Europeans have played lead roles. Indeed, the multi-cultural interest has broadened the base for appreciation of Chinese opera in an evolving art scene.

Multi-culturalism has also helped him to push the boundaries of the art. “All art forms are dynamic,” says Dr Chua. “They change over the years. My operas always keep the aesthetic principles intact. For example, in Ramayana, I kept the storyline but reset it in ancient China. In Mahabharata and Tale of Bukit Merah, I use Indian and Malay costumes but keep the original names of characters, and the music and songs are in Chinese opera style.

The music and movements determine that these experiments essentially remain Chinese opera. Being able to portray the diversity of cultures is so beautiful.

When the children performed in Denmark, we did The Nightingale as a Chinese opera, and the organiser told us that it was the best Nightingale he had ever seen. When we performed in Moscow, we were rated as one of the top three productions.”

Woven into tales told by Chinese opera are values that are worth learning and passing to the younger generation.

Reaching for Roots

Another factor in the revival of the art form stems from a desire to connect with and protect one’s cultural roots, and in this, there’s something for everyone. “Modern theatre and dance practitioners learn and use performing skills from traditional theatre for their creative works; senior citizens learn it to keep fit; and students learn core Chinese values.”

New immigrants to Singapore have also contributed. “Some of the best teachers from China, Taiwan and Hong Kong have formed interest groups at grassroots level.”

With more money coming in for Chinese opera, especially in China, some productions have become so sophisticated that “they can be staged only in big cities and not in the rural areas”. Technology has improved vastly for theatre. Now images can be projected on the screen and floor, with subtitles, superior sound and so on.

Ovation

Dr Chua may have left the COI in 2010 to catch up with his writing, but he remains very much an advocate for Chinese opera and many other Southeast Asian theatre forms at local and international levels. The man has certainly accomplished his mission to bring Chinese opera to a new level of acceptance and appreciation. “The Chinese opera scene is now much more vibrant than before,” he declares. There are not just better facilities but better facilities to perform overseas. And there are good teachers, overseas teachers coming here and performances every weekend, sometimes four in a weekend,” he says. “And over 70 amateur groups.”

He won’t take all the credit for the renaissance of Chinese opera in Singapore, though. He insists that the scene must acknowledge the vision of institutions like the Seng Hong and Feng Shan Temples in Paya Lebar which have encouraged the art with 21-day Chinese opera festivals. Seng Hong had performances for 140 nights last year, “quite an improvement compared to even the late ‘80s,” says Dr Chua. Low ticket prices, $5 to $10, encourage good crowds.

Many temples are increasingly inviting groups from places like Shanghai and Taipei, besides local groups, to perform at their premises. They are also paying performers more than before. “Because many local professional groups perform in temples, if foreign groups are also invited to perform at the same venue, they know the audience will make comparisons, so they try their very best. This kind of informal competition helps to raise the standards.”

Full Circle

Other developments in recent years have especially thrilled him. A 12-year-old girl asked to join the Hokkien Jade Opera Group a few years ago. “You do not expect a girl of that age to ask to join,” says Dr Chua. “I asked her why, and how come she could speak Hokkien? She said that mother brought her to the opera when she was young.”

Over at the 22-year-old Teochew Opera Association, he has noticed “six- to seven-year-olds performing. This is exceptional,” remarks Dr Chua. “I asked one child how come she was performing, and her grandmother answered that when the child was born, she started playing Teochew opera to her, so she has been listening to it since she was a baby.”

It would appear that grandmothers and mothers have been instrumental in Singapore’s new wave in Chinese opera.

Realising that, and remembering his own grandmother, Dr Chua laughs merrily.