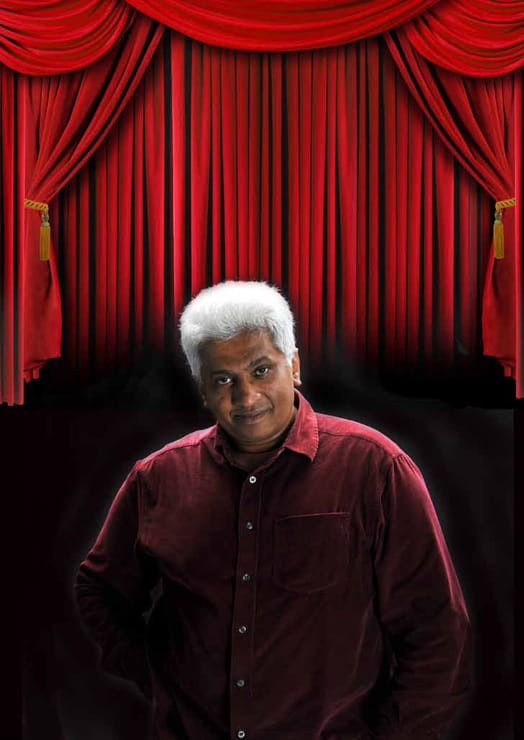

2012 Cultural Medallion Award winner Thirunalan Sasitharan champions the cause of intercultural, interdisciplinary theatre as a force shaping the Singapore identity.

By Kim Lee

When a community calls you by an affectionate short form of your name, it’s a sign you’ve made a mark on it. This impact was confirmed for theatre practitioner Thirunalan Sasitharan, otherwise known as Sasi, when he won the 2012 Cultural Medallion award, the nation’s highest honour for the arts.

“I have been in theatre for 40 years, too long to be doing it for recognition,” commented Sasi, who is Co-founder and Director of Intercultural Theatre Institute (ITI), on the award which was bestowed in October last year. “I was really surprised and gratified that the arts community felt I deserved it,” he added, still unaware of who had nominated him.

Sasi has seen Singapore theatre grow richer and more varied since he was a boy. For sure, more local theatre companies exist today, and their performances are attracting growing audiences. International acts are drawn to play here today, assured of the local talent and support they can find. More significantly, Singapore theatre companies are being invited to perform overseas, and regularly play to full houses. Sasi’s theatre “hobby” dogged his student and professional life until it would no longer allow him to keep it on the sidelines. And recognition was far from his mind when the man acclaimed as one of Singapore’s finest actors first stood before an audience in a tale that began in the most ordinary of ways.

In The Deep End

“I got interested in theatre because we had to do some work in drama at Victoria School in 1971. The teachers threw us into the deep end — write a script and do a performance. Theatre was an extension of my love for literature, for reading, for the literary arts. Then there were opportunities the National Library created for young people who wanted to do theatre — a series of workshops that covered acting, directing, playwriting, all the elements of theatre as they saw it. These were done in English by local practitioners, people from arts companies like the Experimental Theatre Club , the Stage Club, Stars. You learnt everything from making props and doing make-up, to lighting and sound, and these workshops usually ended with a production.

That’s how I got started writing, acting and directing. He then began to audition for performances outside of school, which brought him into contact with many companies and directors. Theatre ran as a parallel track to his life. At the National University of Singapore (NUS), where he studied philosophy, he was in the theatre more often than in the lecture halls. His parents reminded him that he should be focusing more on work and maybe get practical skills like typewriting, but they also gave him the freedom to do what he wanted. In spite of his passion for it, Sasi “never intended to make a living from theatre”.

Perhaps it was inevitable that theatre would lead him to dramatist and arts activist Kuo Pao Kun, a pioneer of Singapore theatre and an earlier Cultural Medallion recipient. They met in 1981, when Sasi was a university student. “He came to see me after I did a play,” recalled Sasi. “He started talking about some of the work he had seen me do and invited me to be part of a project, writing a script with him and then performing the work. That turned out to be No Parking On Odd Days, the first play in which he directed me. After that, I would do a play with him almost every year.”

Kuo introduced Sasi to a different world. “I came from English language theatre. Pao Kun, at that time, was still a Chinese language theatre person. I began to see how the Chinese theatre community, Chinese actors and directors were working — and it was very exciting to know that there were other Singaporeans like me who shared a history working in theatre. It deepened my understanding of theatre and my appreciation of theatre work. Of course, Pao Kun was a remarkable writer, director and playwright.”

A meeting of minds and artistic souls with late Singapore theatre scene pioneer, Kuo Pau Kun. Photo: www.plussixfive.com

Theatre continued to shadow Sasi’s student days into his professional life, first as a philosophy lecturer at NUS and later as arts writer and editor for The Straits Times newspaper, before claiming him full time. “In 1995, Pao Kun asked me if I would like to run the Substation. Because he asked me, I said yes,” said Sasi. Kuo started The Substation, Singapore’s first independent contemporary arts centre, in 1990 and became its first Artistic Director. Sasi took over in 1996.

A Singaporean Sensibility

By then a local English theatre community had already taken root, in contrast to earlier times when theatre had little Singapore character. Theatre was Chinese, Malay, Indian or English, but all foreign in origin.

“By the late ’70s into the ’80s,” said Sasi, “part of the consciousness of ourselves as a people, as a community, a city, began to develop, and a Singaporean consciousness began to be recognisable onstage in many ways.

It started in the late 1970s, with people like Goh Poh Seng and Stella Kon, and later Ovidia Yu, writing plays in English. A unique sense of Singapore began to emerge in plays like Emily of Emerald Hill on the local Chinese Peranakan community, and Mama Looking For Her Cat, Singapore’s first multilingual play. “It became clear that there was a viable Singaporean identity which could be presented on stage,” said Sasi.

“It didn’t need to be English-speaking or have an English consciousness. It was an identity about the multitude of linguistic identities we have in Singapore. There was Chinese, Malay, Indian theatre, and the combination of all this was what Singapore theatre was all about.”

Actors for the new millennium are trained in a multilingual, multicultural and interdisciplinary context. Photo: ITI

After five years at the Substation, Kuo came to Sasi with thoughts of closing down The Practice Performing Arts School. He had co-founded the school which had been instrumental in grooming local talent since 1965, but felt it was time to stop teaching and focus on his own creative work.

“Closing Practice meant nobody was going to be teaching younger people,” said Sasi. “There was no theatre in schools like we have today. The theatre I did in school was exam-based. I said, ‘Don’t shut down Practice. I will leave the Substation and come and join you. We will set up a programme that will teach actors how to act.’”

The duo founded the Theatre Research and Training Programme (TTRP) in 2000. It crafted a unique curriculum for training actors how to act in a multilingual, multicultural, interdisciplinary context for the new millennium. Originally a part of Practice, TTRP took on a life of its own as it became a private school in 2010 offering its post-graduate level acting course. It was relaunched as the ITI in 2011.

“The quid pro quo,” said Sasi, “was that he teaches me directing and I run the programme. And he said, ‘Sure, that’s a good deal.’ But he passed away in 2002, in the second year of the programme, so I was left carrying the baby. It was devastating to lose Pao Kun. He was a friend and partner and I didn’t know whether I should or could go on. In the end, I felt that firstly, I owed it to him, and secondly and more importantly, this was what I still wanted to do — work in theatre, train people in theatre, influence the theatre scene, and not just in Singapore. By that time, interest in the programme was worldwide…so it was not just about Singapore theatre.

“Nobody was offering a practical programme for working actors that didn’t require academic credentials. We picked and we still pick our students from auditions. They have to have acting experience in theatre. The essential aspect of the programme is that you become immersed in Asian traditional theatre…and work in contemporary theatre. It’s very specialised, niche training but it appeals to actors who are searching for something new, something original, something which is outside the boundaries of commercial theatre.

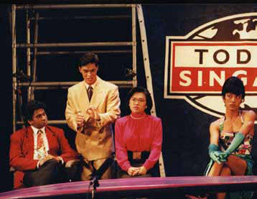

Private Parts explored the lives of two transsexuals in this 1992 performance with Sasi (left). Photo: TheatreWorks (Singapore) Ltd

“We felt that we needed to empower the actor to be an active agent in the process of making theatre. Commercial theatre doesn’t allow you to do that. You play a role, you get paid your contract rate and then you go. I think 90% of theatre is like that. But there is a 10% theatre fringe where the actors, the directors, the writers have some control over the material they put out. This is not going to be commercially viable, not going to be profit-making. It has to be subsidised, it has to be based on the needs of a community…it is much smaller work but more interesting work of experimentation in theatre. A lot of the new thinking happens in this area.”

ITI demands that its students be socially aware because their work is intended to resonate with their communities. The independent theatre school has an alumni of graduates not just from Singapore and nearby Malaysia but also from India, Japan, Macau, Philippines and Taiwan, and yet further afield from Mexico and Poland.

Retrospective

“Sometimes it takes a decade before you begin to see the value of the kind of investments you make in culture and art,” said Sasi. “The one thing that is unchanged throughout these 40 years that I have been involved is that we, as a society, need to consistently have serious engagement with culture and in our own cultural development. We need to be thinking about it, and be concerned about it because it shapes the way our children think and look at the world. And I think it gives us a sense of confidence about who we are. “This is not to say that we are not confused. We have doubts about ourselves, we question things and all that, but we are stronger for it as individuals and as a society. This is very, very important. I think the arts in general — and theatre in particular — do that for us.

“And there is no way we can measure it —

this is the great danger because so much of our lives in Singapore is about measurement: KPIs (key performance indicators), quantifiables and all that. But beneath all of that is immeasurable strength that we need to invest in, as much as we do infrastructure, development and all the other things we are now investing in. And we need to do that not just as a nation, or a government, but from the level of a person.”

The Singapore International Foundation‘s Singapore Internationale programme supports Singapore artists in intercultural collaborative work with artists overseas. In 2012, it helped to present 108 works by 92 artists in 34 countries.