Stories > Big Hearts that Give Hope

Big Hearts that Give Hope

From sewing personal protective equipment to donating meals to the needy, individuals and ground-up initiatives across Asia have come together to support frontliners and vulnerable communities amid the ongoing pandemic.

BY AUDRINA GAN

hile the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted lives and caused hardship for people around the world, initiatives advocating the spirit of humanity in times of crises continue to proliferate.

Our Better World (OBW)’s HumanKind series, from the Singapore International Foundation’s digital storytelling platform, tells such stories of courage, goodwill and collective effort that played out during the peak of the ongoing pandemic. Focusing on frontline workers and vulnerable communities, who have been negatively impacted by the global lockdown, the series casts light on how local communities came up with ingenious solutions to help the needy in the face of one of the worst healthcare crises of our times.

OPSROOFUP

A self-made entrepreneur, Delane Lim, 35, is the former CEO of Agape Group Holdings, which empowers and equips young people with the necessary personal development as well as character traits to achieve their fullest leadership potential. Now working as the executive director of Formwerkz’s Group (an architecture, design and tech firm in Singapore), he started the social initiative OpsRoofUp.

The movement was initially aimed at rough sleepers who had nowhere to go after a mandatory stay-at-home order implemented by the Singapore government, as well as commuting Malaysian workers unable to return to their homes due to border control measures. Since then, it has expanded to include the poor and elderly self-isolating at home with little access to basic necessities.

Lim explains that he worked with different organisations to provide the stranded with temporary abodes at interim shelters, such as Transit Point in Margaret Drive and Safe Sound Sleeping at Yio Chu Kang Chapel – while catering to their dietary needs. More significantly, he pulled together different individuals hit by the crisis, such as catering companies and taxi drivers, to enable them to cover rental costs and overheads.

Delane Lim (right) launched OpsRoofUp to help stranded Malaysian workers in Singapore after the border closures kicked in.

“By establishing long-term relationships with a few catering firms, we could provide them with some business during this trying period, when many such food establishments suffered a loss of income,” he elaborates. “Utilising the taxi drivers’ network also makes it easy to contact other drivers who are interested to participate in this endeavour.”

Lim reaches out to the needy through referrals and canvassing neighbourhoods. He recalls a memorable incident where he and a couple of volunteers were walking around the parks in the northern part of Singapore looking for homeless people.

“We couldn’t find any who needed help, until we came across two men sleeping at one of the shelters. They were Malaysian workers who would commute between Johor Bahru and Singapore everyday, but found themselves with nowhere to sleep during the Circuit Breaker. They were exhausted after braving the traffic jams to rush to Johor Bahru to see their families before the cross“We couldn’t find any who needed help, until we came across two men sleeping at one of the shelters. They were Malaysian workers who would commute between Johor Bahru and Singapore everyday, but found themselves with nowhere to sleep during the Circuit Breaker. They were exhausted after braving the traffic jams to rush to Johor Bahru to see their families before the cross-border travel restrictions kicked in, and returning to Singapore the same night.

“As the weather was quite cool at the time, they were thankful for the OpsRoofUp care kits. Each kit contained a hand sanitiser, masks, shampoo, soap, toothpaste, sleeping bag, light snacks and fruit to help them tide through the night,” he recalls. “It was heartening to know that these workers could at least have a good night’s rest before starting work the next day. But I found it hard to sleep that night knowing that there were still people out there who did not have the luxuries that I did.”

“While Singapore is an affluent country, we also need to remember that not everyone is fortunate enough where they don’t have to worry about the daily necessities.” Delane Lim, founder, OpsRoofUp

The initiative has expanded to help more vulnerable individuals; Lim also engaged the services of taxi drivers for food distribution.

The initiative also utilises online platform Giving.sg to source direct contributions from the public. While there isn’t a minimum amount to contribute, a S$10 (US$7.50) donation can fund two meals and one breakfast, and the remaining S$2 goes to the volunteer taxi or private hire drivers.

Alternatively, donors can purchase a bundle set from F&B partner Chef-in-Box, which includes four days’ worth of meals. For each purchase, 10 per cent of the proceeds is donated to OpsRoofUp. Customers can choose to keep the meals for themselves or share it with someone in need. OpsRoofUp then uses the proceeds to purchase more food supplies as well as provide the transportation fees of taxi drivers assisting with the food distribution.

To date, Lim’s team has delivered daily meals, sweet treats and essential items to more than 10,000 vulnerable individuals. “We recruited 37 volunteers and 18 drivers – each earning an average of S$1,100 for the whole duration,” he shares. “The coverage on OBW has enhanced public awareness for the work we do. Through increasing donations and a higher number of volunteers, we are able to ensure that the needy get the daily necessities they require.”

He is also frank about the initial challenges, such as logistical coordination and ensuring that the catered food reached their intended venues on time due to the expiration times. “Besides bringing all the stakeholders together, it took meticulous planning and plenty of preparation to get it all done. We even had to ensure that the recipients ate their food on time!”

He adds that the experience of running OpsRoofUp has helped him to better appreciate the simple things in life. “It can be something as simple as having a roof over my head and food to eat every day,” he contemplates. “We are so accustomed to these basic things that we take them for granted. This was a good wake-up call – that while Singapore is an affluent country, we also need to remember that not everyone is fortunate enough where they don’t have to worry about the daily necessities.”

Young Filipinos Charisse Parchamento (left) and Erika Ente (centre) started a non-profit during Covid-19 to help the homeless and needy find temporary shelters. They also provided food as well as PPE kits and disinfectant alcohol for Metro Manila’s hospitals.

#MAYTWENTYAKO

“How can the homeless stay at home if they don’t have homes?” This was the first thought that occurred to 19-year-old Charisse Parchamento when the enhanced community quarantine, which mandated Philippines residents to stay indoors, kicked into effect back in March 2020.

Despite having an iconic cityscape and historic national parks, Metro Manila – where she resides – also has the world’s largest homeless population. Over three million people, a quarter of the city’s population, are estimated to be struggling with poverty.

As its name implies, the movement encourages people to donate as little as 20 pesos (US$0.40) – the smallest denomination in the Philippine currency – to buy grocery packs and hygiene kits for the homeless and informal workers.

The non-profit’s small donation initiative has quickly gained ground among those wanting to help the needy.

“Some people are discouraged from donating because they feel that they will be required to give a lot of money,” she says. “We believe we can change this mindset because everybody has a spare 20 pesos that they can allot to a good cause like this.”

When Parchamento and Ente launched the fundraising campaign on their social media accounts, their initial target was to raise 2,000 pesos to purchase 100 hand sanitisers for homeless people in Malabon City. After five hours, however, the donations surged to 30,000 pesos, which enabled the duo to buy bread and grocery items for the informal workers and homeless in CaMaNaVa, an administrative division in Metro Manila comprising the four districts of Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas and Valenzuela, and the municipality of Bulacan, located north of Metro Manila.

“I ALWAYS REMIND MYSELF THAT THIS WORK IS NEVER ABOUT THE PEOPLE BEHIND THE ORGANISATION BUT THOSE WE ARE HELPING,” SAYS CHARISSE PARCHAMENTO, CO-FOUNDER, #MAYTWENTYAKO.

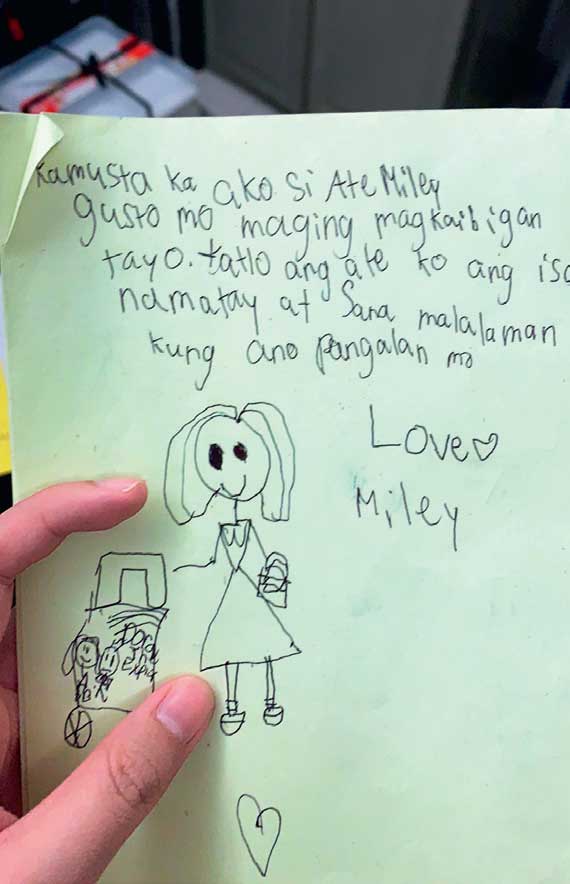

An appreciation note for the volunteers by a young beneficiary; the initial #MayTwentyAko campaign raised enough funds to buy basic groceries for several informal workers and homeless people.

A week into the campaign, they started receiving messages from communities who wanted to be part of a similar initiative. “We now have recognised #MayTwentyAko campaigns in the provinces of North Caloocan, Pampanga and Cavite,” says Parchamento. The youth-led movement quickly grew to 13 people, including 12 young people aged between 17 and 27 years, and a 53-year-old who is the mother of three volunteers.

From having to obtain a special pass to get around the city to promptly securing items from the suppliers of personal protective equipment, disinfectant, hand sanitiser and liquid hand soap who are located outside of Metro Manila, the initiative faced its own set of challenges. “We practically pleaded with the authorities to let us have the City Hall because we knew we had to continue our distribution efforts,” recounts Parchamento.

At one point, only four of her team were left to pack and distribute items as the other volunteers were minors who could not participate. Through it all, they continued to generate awareness about their work.

For instance, through the Project Pa-Print, the team worked with 25 public schools with no access to online teaching resources by helping them to print worksheets and modules for the students. Copies of the worksheets were sent to the volunteers for printing and then delivered to the school. They also came up with creative ways to raise funds, such as selling milk tea, tote bags as well as a jersey auction of renowned Filipino athletes, with all sale proceeds going towards the fundraising.

The coverage on OBW has also helped to drive overseas donations. “At one point, we were about to buy 60 gallons of disinfectant alcohol to give to the public hospitals for sterilisation purposes and the price was about 24,000 pesos,” she recalls. “Just then, an overseas Filipino worker in Singapore donated 22,000 pesos, which enabled our purchase.”

To date, MayTwentyAko has distributed surgical masks, gloves, face shields, head caps and meals to hospitals in Metro Manila, Batangas, Mindoro, Cagayan, Pangasinan, Bukidan and Laguna. It also worked with two Catholic schools by using their premises as temporary shelters for the homeless.

“I always remind myself that this work is never about the people behind the organisation but those we are helping,” says Parchamento. “The latter are individuals with real problems and they deserve long-term solutions, which I know is beyond what we can do. But in the future, I am hopeful that we can come up with sustainable solutions such as livelihood programmes.”

FASHION FOR FRONTLINERS

The year 2020 was supposed to have been a grand affair for Malaysian fashion designer Melinda Looi as it marked the 20th anniversary of her eponymous label. Instead, she found herself putting her sewing skills to use to make personal protective equipment (PPE) for frontline medical staff.

Volunteers from different socio-economic backgrounds pitched in to provide suitable PPE materials, as well as cut, sew and distribute them to frontline medical staff across Malaysia.

When the Movement Control Order (MCO) was imposed in March 2020 to prevent the further spread of Covid-19 within Malaysia, a friend tagged Looi in a social media post about the country’s medical staff facing a huge shortage of PPE, with many having to cut and sew their own.

“I thought this was not right. The duty of these medical personnel is to keep us safe. But they now also have to make their own PPE,” she recalls. As president of the Malaysian Official Designers Association (MODA), she called upon other members of the organisation and asked if they would like to contribute. “MODA members and friends pitched in to help, and the initial team of five to 10 volunteers grew quickly as the word spread throughout their network and social media,” she shares.

Soon, more individuals got in touch with her, wanting to contribute. “We do not know the exact number, but there were a few hundred volunteers comprising both adults and children who pitched in to help, some despite having their own challenges,”she says. “One family with young children came with the cut aprons, and there were low-income donors who asked if they could donate just RM5 (US$1.24) or RM10.”

Malaysian fashion designer Melinda Looi (right) with volunteers who stepped up to contribute towards the project.

She also managed to rope in several fabric manufacturers in Malaysia who helped to prepare the required non-woven materials. “It was tough to reach out to the suppliers for raw materials such as Velcro and threads during the MCO,” she shares. On the distribution end, she was assisted by the Islamic Medical Association of Malaysia’s Response and Relief Team.

“Travelling outside of Klang Valley was a big challenge. A few transportation volunteers helped us to send the PPE materials to Perak, Penang, Malacca and Negeri Sembilan,” says Looi. Hospital Kuala Lumpur also helped with authorisation letters, which allowed them to bypass the road blocks. To date, the team has delivered more than 300,000 PPE and over 200,000 pieces of plastic aprons across Malaysia.

Words of gratitude and encouragement have bolstered Looi and her team’s efforts. “Some frontliners sent us messages about how depressed and miserable they felt when they had to wear garbage bags as PPE and not knowing if they were wellprotected. Some even did a dance with the PPE on TikTok to thank us,” she shares.

The story told on OBW had also helped to raise both awareness for Looi’s cause and donations to the tune of RM10,000.

“We are thankful for the opportunity to show that no matter when, what and how you give, there is always a way to help someone,” she observes.

Scan the QR code or visit

www.ourbetterworld.org/series/humankind

friend-life-and-death to find out more.

more.