Stories > Cradles of Culture

Cradles of Culture

Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum weaves a cultural narrative through diverse communities spread across the largest continent on the Earth.

BY SHWETA PARIDA

PHOTOS ASIAN CIVILISATIONS MUSEUM

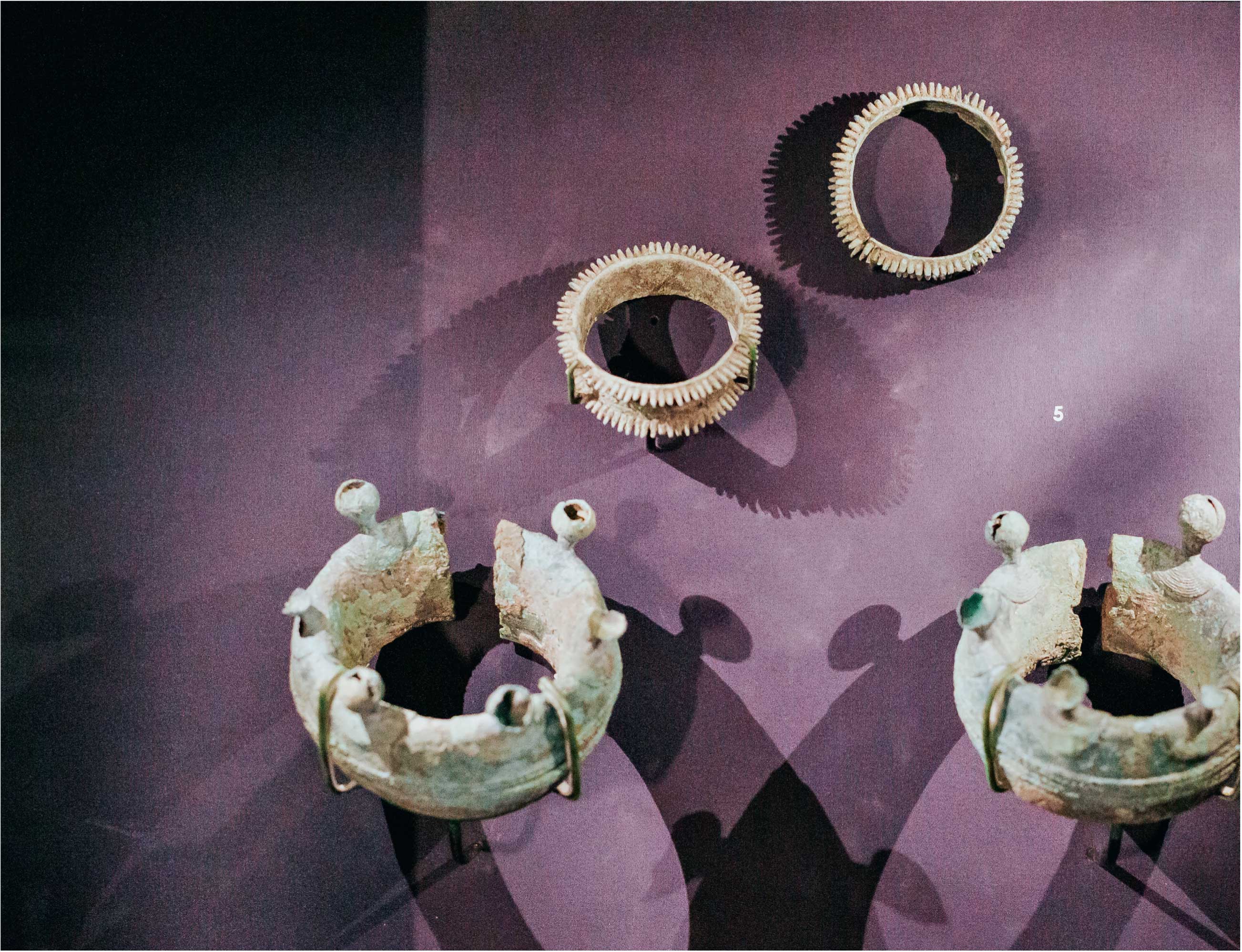

The jewellery exhibits at Asian Civilisations Museum provide a glimpse into the way of life of indigenous communities in Asia, going back to the 18th and 19th centuries and some even earlier.

s one of the mainstays of Singapore’s public art realm, the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM) is more than just art history; it is an evolutionary display of global cultures and communities that have, since centuries, intersected and flourished alongside each other.

While it continues to traverse historical eras, the museum has recently shifted its ethnocentric geographical focus towards decorative arts that encapsulate the past through tangible heritage.

“Since I took over this role four years ago, the most challenging as well as exciting part about my job has been to shape the ACM for a new world,” says Kennie Ting, director of the ACM. “While the ‘old ACM’ worked very well for its time, we had to shift in tandem with the changing world and make sense of older things in a new perspective.”

“We moved away from the idea that cultures and regions originated and thrived in silos, to one that demonstrates cultures have always been connecting and interacting with each other.”

Kennie Ting, director, the Asian

Civilisations Museum

He shares that the shift is underscored by two interlinked aspects. The first of the two strategies was to move away from the geographical approach towards one that was thematic. These themes – maritime trade, faith, materials and design – are explored through the arcs of history and shed light on civilisations and their evolution.

Exquisite porcelain items from around the world at the Ceramics Gallery

“We moved away from the idea that cultures and regions originated and thrived in silos, to one that demonstrates cultures have always been connecting and interacting with each other,” he says, adding that the realignment helped to dispel the theory of typecasting cultures.

The new orientation is also one that emphasises Singapore’s outward vision and its place and role in the global discourse. The shift in direction wasn’t without its challenges, however. There was scepticism among the experts about exploring art history through decorative objects.

“The premise of the ACM is about focusing on cultural exchange, and that hasn’t changed at all, but there is a way of objectifying art that is not quotidian,” he reasons. “Traditionally, in art history, decorative art is somewhat of a lesser form and the underlying perception is that furniture is not all that important. But the human element is much stronger in these objects – they are both beautiful and functional.”

Exhibits from the 9th century Tang shipwreck.

Last year, the museum introduced the fashion and jewellery galleries that aim to reach out to a younger audience, and keep history relevant by connecting art with everyday life by showcasing the jewellery and costumes worn by different communities during various periods. These pieces range from jewellery worn by the Javanese during 8th century Indonesia to the Chettiars from India’s Tamil Nadu during the 19th century and the Minangkabau from western Sumatra during the early 20th century, among others.

“These exhibits not only allow us to celebrate the people who made them, but provide a glimpse into civilisations and how the lives of people have evolved over time,” Ting posits.

IMPACT OF MARITIME TRADE

One of the revelations of the new approach was that there was an entire genre of made-in-Asia luxury and decorative objects that were specifically for global export. At the ACM, the displays provide a sense of geography and chronology.

“You can see the timeline of history and maritime trade with Asia from the 9th century to the early 20th century, and you get a sense of the development of crossborder trade within Asia as well as between Asia and the West,” says Ting. “This outlook enables the ACM and, by definition, Singapore to be a thriving cultural hub that presents a comprehensive view of Asian art trade.

“For example, we have some pieces produced during a specific time period of the Dutch East India Company from Batavia [present-day Jakarta], the Portuguese from Goa and Macao, the British East India Company from different territories, and the Spanish from Manila. This juxtaposition of pan-Asian cultures allows us to compare what people desired across various trading communities and eras, and the differences between them.”

Ceramic artwork (top) at the ACM establishes centurie sold trade connections between diverse communities; a 20th century ginger rootshaped clay teapot (below) from China’s Yixing county.

CIVILISATIONS AND CRAFTS

To contextualise the ACM’s new mandate while staying true to its multicultural premise, Ting points out that it was important to move away from the ethnography-based museum – a concept that is Eurocentric – that formed the second aspect of the shift and an extension of its thematic approach. While earlier, the curatorial process meant setting up the context and then rationalising it through the exhibits, it now expounds the theory that each object has its own story.

“For many centuries, the rest of the world has looked towards Asia for the production of highly desirable objects – from Chinese porcelain to Indian textiles and furniture from Southeast Asia and Japan. The new Asian renaissance seems to have compelled the region’s youth to re-examine their own heritage hinged on innovation,” he reckons.

“We often tend to forget that this craft excellence has been here for centuries, and during the difficult period of colonialism, this art was taken and destroyed or systematically undermined. It’s, therefore, important for the ACM and Singapore to champion not just their preservation but innovation in traditional crafts.”

This reconciliation with the past has become the lens through which the ACM now envisions its exhibitions. Citing the example of the critically acclaimed 2019 showcase of Chinese couturier Guo Pei’s presentation, he says: “After the positive feedback on the exhibition, we realised that art collections can be a huge source of inspiration because Guo Pei was inspired by our Peranakan collection.

“THE CHINESE WEDDING ENSEMBLES IN THE [ACM] EXHIBITION WERE INSPIRED BY PERANAKAN BEADWORK. IT’S IMPORTANT TO APPRECIATE AND PRESERVE SUCH HERITAGE BECAUSE IT BELONGS TO ALL MANKIND,” SAYS CHINESE MASTER COUTURIER GUO PEI.

“In fact, the collaboration prompted her to reintroduce a bridalwear range in China where this practice hasn’t been prevalent since the cultural revolution of the late 1960s and 1970s.”

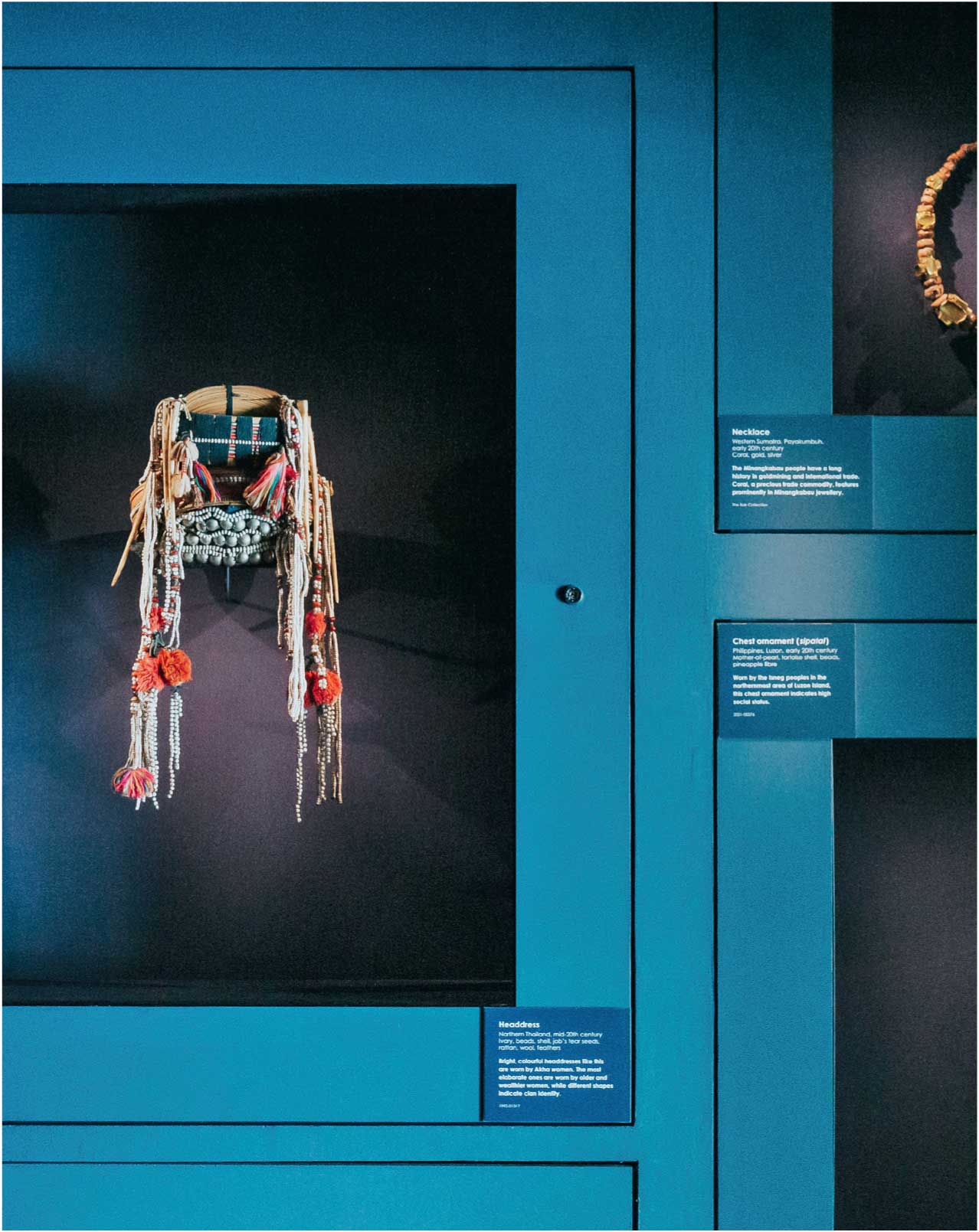

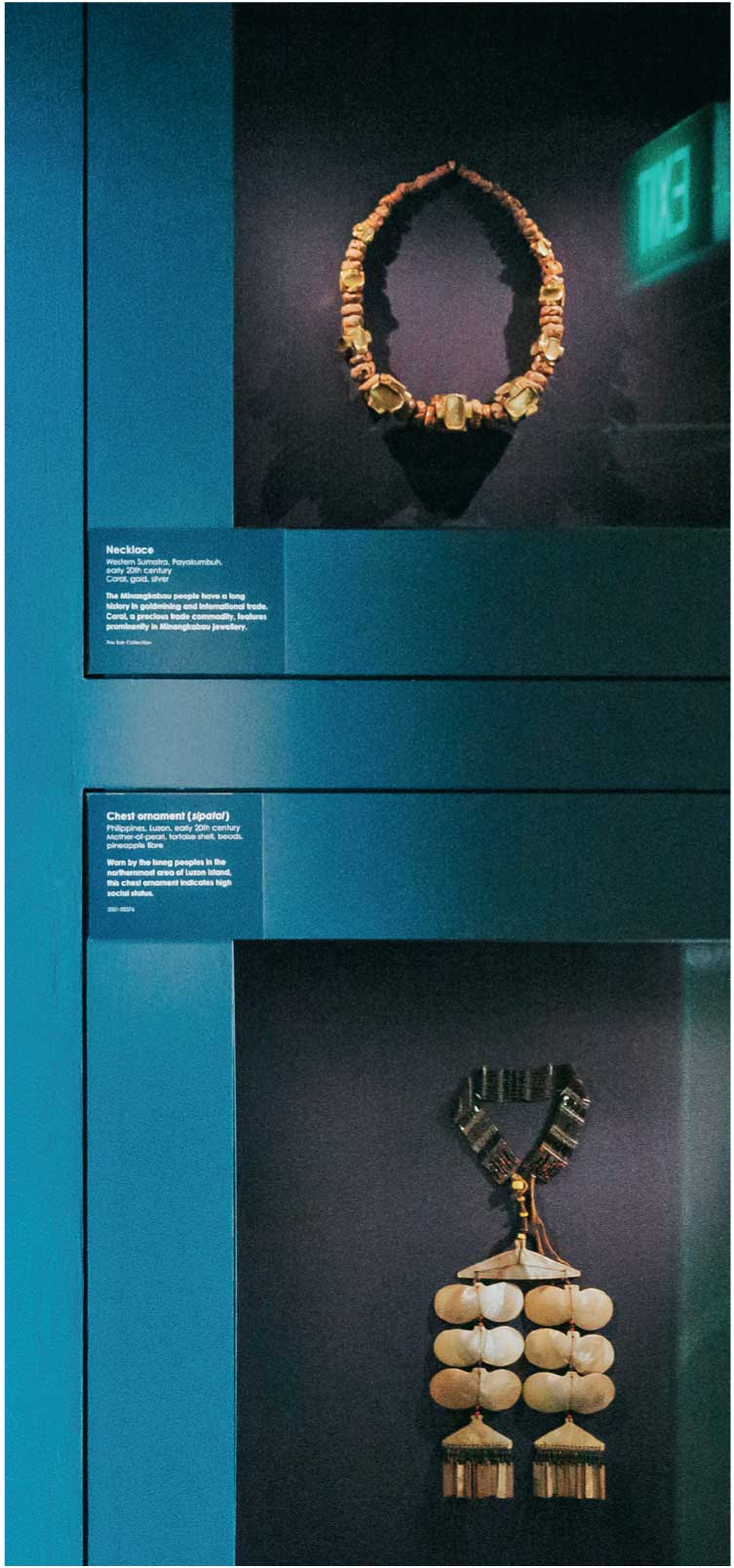

Bright headdress worn by Akha women in the mid-20th century in northern Thailand; necklace worn by the Minangkabau community in early 20th-century West Sumatra; and an early 20th-century chest ornament worn by the Isneg people of Luzon Island in the Philippines.

For the master couturier, it all started when she visited a travelling exhibition on Peranakan art and bridalwear presented by the ACM at the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris back in 2010. Describing it as a serendipitous moment, she likens that visit to an epiphany.

“When I saw it, I felt like I had finally found what I had desired. It was something I had been searching for all my life and it was right in front of me,” she enthuses. “And years later, with the exhibition at the ACM, it seems like we have come a full circle. The Chinese wedding ensembles in the [ACM] exhibition were inspired by Peranakan beadwork. It’s important to appreciate and preserve such heritage because it belongs to all mankind.”

EVOLUTION OF CULTURES

Tying back to the two-pronged mission of the refreshed ACM, Ting emphasises that it’s important to understand that cultures have never been static.

He cites the example of one of the displays at the newly opened costume and fashion galleries. Titled Fashion Revolution, it explores the evolution of modern Chinese dress – from the Qing Dynasty to the Republican Era qipao and the Mao suit.

“We turned around this notion of the national dress in China that people typically associate with Chinese imperial robes – the qipao and Mao suit,” he says. “The qipao and even the Southeast Asian garments, for example, have been influenced by Western style of constructed tailoring.”

Despite the trade and cultural relationships dating back hundreds of centuries, Ting says that, surprisingly, there still isn’t a widespread awareness of the extent of interactions between different cultures within Asia, and between Asia and the West.

“Visitors to the ACM are often surprised to view the intercultural narratives of Asian culture and history,” he adds. “Because Singapore is a blend of East and West, we are able to present a non-nationalistic view of Asian culture and art.”

Minangkabau bride in the 19th century.

BUILDING NEW RELATIONSHIPS

Not surprisingly, the nature of Ting’s work brings him into close contact with international counterparts. “Recently, we had an international symposium on the Silk Route that was organised as a webinar due to Covid-19,” he shares. “It was meant to coincide with our Tang shipwreck exhibition opening in Shanghai. We pulled everyone together from China, India, Japan, the US, Europe and Southeast Asia who are experts in different areas such as art history, archaeology and ship building to conduct further research in this area from a crosscultural perspective.

”Visitors to the ACM are often surprised to view the intercultural narratives of Asian culture and history. Because Singapore is a blend of East and West, we are able to present a non-nationalistic view of Asian culture and art.”

Guo Pei’s exhibition at the ACM also sheds light on China’s centuries-old traditional crafts.

“Even in our exhibitions, we find crosscultural angles in research and planning,” he shares. “For example, our exhibition on the Raffles Southeast Asia exhibition in 2019 was a complement to our Angkor exhibition in Phnom Penh that took place in 2018. Both tackled colonialism and its legacy in Southeast Asia.”

Following the success of Guo Pei’s costume exhibition, he and his team are working on curating more of such expositions. “We have more couture exhibitions by master craftsmen lined up from different parts of Asia such as India and Southeast Asia,” he says.

While the special exhibitions were meant to be held every two years, the ACM has had to adjust the schedule due to the ongoing pandemic.

Ting’s ambition is to establish the ACM as a treasure trove of inspiration for Singapore’s own creative industry practitioners along the lines of London’s iconic Victoria & Albert Museum. “We have to help our designers and artists find their own voice through these stories,” he says.

Cultural sensitivity plays a vital role in cross-cultural collaborations, and Ting is acutely conscious of its significance. He cites yet another example – the Raffles retrospective – that required pieces from British museums as the exhibition was co-created with them.

Exhibits at the ACM’s fashion gallery include items such as shoes for bound feet worn by women in 19th century China.

At the same time, the showcase drew parallels with the Dutch legacy in Indonesia. Ting flew to meet his counterpart at the National Museum of Jakarta to ensure that they were comfortable with the portrayal of Indonesia’s colonial past as well as to involve them in the academic programming of the show.

Navigating global cultural sensibilities, he has also gleaned new lessons. Being from a young nation, he believes it’s important to be respectful and open-minded. “It’s alright for us to admit that we’re fairly young and are here to learn from them, while charting our own path,” says Ting.

PORTS OF ARRIVALKennie Ting examines the intertwined relationship between port cities and diverse communities globally. Having adopted the role of Asia’s cultural flagbearer, the ACM has been able to contextualise its vision through the history of Singapore. It highlights the strategic roles of trade and faith as two of the driving forces of the city state, whose identity as a port city has been the genesis of not just its physical development but its cultural core. Further elucidating the role of Asian ports in propelling the growth of civilisations, Ting says that while Singapore isn’t the only port that thrived on the basis of being strategic to the trade routes and cosmopolitanism, it remains unique. “Post-war, many of the port cities such as Mumbai, Canton, Malacca and Shanghai, and even London and Venice in the West, turned inwards, but Singapore has remained uninterrupted in its belief,” he theorises. Amid the wider discourse, the ACM also enables the lesser-known communities in Asia to find their own place. Communities such as the Chitti Melaka – Hindu Tamil people who settled in Singapore and Melaka and adopted many of the Chinese and Malay practices, earning the sobriquet of Indian Peranakans – the Mestizos of the Philippines (a Filipino community with mixed European heritage) and the Anglo-Indian (people of mixed English and Indian descent) provide a glimpse into the cosmopolitan zeitgeist of the time. “We have always been fascinated by these small but culturally-rich mixed communities that have developed their own hybrid manifestations of material culture,” says Ting. The ACM’s pan-Asian perspective sheds light on many other communities such as the Armenians, Arabs, Jews and Parsis, who lend their diversity to Singapore. |