Stories > Frontline Allies

Frontline Allies

Singapore’s top medical academics highlight the significance of establishing international partnerships and connectedness in light of the Covid-19 global pandemic.

BY ANNIE TAN

day, professor Dale Fisher fights Covid-19 on the frontlines as senior consultant at the National University Hospital and professor in infectious diseases at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. After official working hours, he transforms into the hero of a popular comic series on the pandemic.

Meanwhile, associate professor Jeremy Lim Fung Yen dedicates much of his career to grooming the next generation of health leaders at the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. When he steps out of the lecture hall, he and his team assiduously advise government officials around the world, and work with media teams to produce social media videos for Singapore’s 400,000 migrant workers.

Even as the Covid-19 pandemic has upended lives around the world, it has led to important and sometimes unexpected medical collaborations. In an increasingly connected world, this seems more relevant than ever.

Professor Dale Fisher of NUS YLLSM (centre, with glasses) during a hospital visit in China in February 2020, when he was collaborating on a Covid-19 international mission.

JOINING FORCES

Indeed, a few short weeks after the first cluster was reported in Wuhan, 25 experts from China and across the globe assembled for the WHO-China Joint Mission on Covid-19. Prof Fisher was selected to be one of the members in the special task force committee.

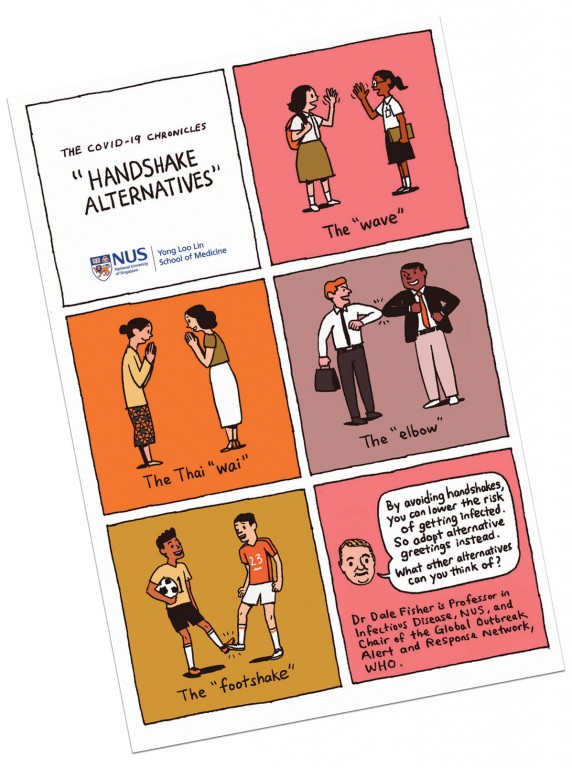

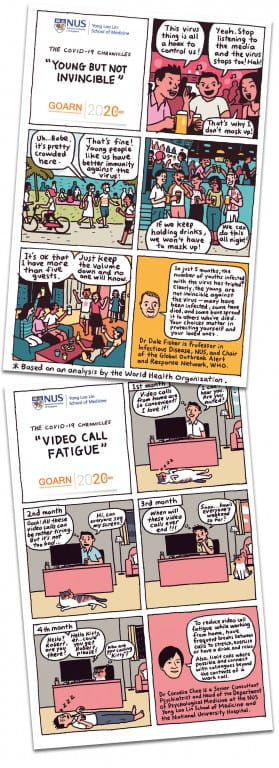

The Covid-19 Chronicles educates the public, and features prof Fisher as its main character and expert.

With hardly any substantial information in hand, the team started its trip in Beijing. They then split into teams to visit hospitals and speak with medical teams in Guangzhou, Chengdu and Wuhan. Even in those early days, the scale of the outbreak struck prof Fisher. “[China] had good contact tracing and testing, but despite all that, they had to lock down the whole country. There was hardly anyone on the streets, and everyone was wearing a mask,” he recalls.

The insights from this mission laid the important groundwork for some of the information we take for granted today, such as higher death rates among the elderly, the relative safety of children, and elevated risks in people with immuno-suppressed conditions.

That was mid-February 2020. Fast-forward a few months: The outbreak has progressed into a full-blown global pandemic that has afflicted more than 38 million people and killed over 1 million*. Medical collaboration picked up around the world to keep pace with the daily findings on coronavirus and its rapid evolution. Top universities released a spate of reports and webinars. In Singapore, the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health (SSHSPH) began to produce weekly reports on research and practice in Covid-19.

This not only became a useful reference for the medical community, but also an invaluable resource for national and global policymakers. Stepping beyond the traditional academic role, the faculty has also been providing advice pertaining to Covid-19 research to government officials around the world, including those in Europe and Africa.

“The First Thing A Public Health Professional Needs To Do Is To Understand The Needs And Beliefs Of The Local Population – And Work Within That System, In A Collaborative And Respectful Way, To Devise Public Health Strategies.”

A GROUND-UP FIGHT

One thing quickly became clear to healthcare experts – since Covid-19 is spread among the community, it must be addressed at a community level. Standardised messaging and clear public communication were vital.

Prof Fisher, who is also chair of the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), had already seen the importance of this in previous outbreaks such as Ebola, for which he had travelled to Liberia in West Africa thrice between 2014 and 2015.

“I was there with the World Health Organization [WHO], but there were other groups such as CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] from the US, Red Cross and several non-government organisations [involved in infection control] from around the world. Everyone was saying something slightly different, and there was a lot of confusion about when to wash your hands, and what to wear. When people are anxious or unsure, even small differences [add up],” he shares.

The team spent a week drafting an infection control guideline, replete with PowerPoint slides, word documents and posters. This was adopted by the Liberian government as their national training package, replacing all other materials to avoid confusion for better outbreak response through standard operating procedures.

Applying these insights to the ongoing Covid-19 outbreak, prof Fisher helped to create a standardised message on what to wear, how to practise social distancing and other safety precautions. He communicates with the WHO almost daily and joins a global health leaders’ meeting every week to further develop these guidelines and recommendations.

This is all in a day’s work for the professor. What he did not expect, however, was the day he was invited to be a comic character, albeit for a good cause.

“When [Singapore’s Minister of Health, Gan Kim Yong] asked me if I would step up as a face to help with messaging, I thought he was talking about going on Channel NewsAsia or something,” he laughs.

“When they put the cartoon together, I was initially reluctant because as a senior doctor, I wondered if becoming a cartoon character would trivialise [my role].”

After discussion with a few friends, the prof gamely embraced the challenge. The Covid-19 Chronicles by NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine was born. With bite-sized tips on how to navigate the new normal, it has garnered more than 3.5 million views, and has been translated into languages such as Japanese and Italian.

CROSS-BORDER AWARENESS

Language, however, is just one of the many barriers when it comes to international cooperation. Having been on many international medical missions, associate professor Jeremy Lim knows the importance of being “plugged in” to a global outlook with a first-hand experience.

Prof Teo Yik Yee (third frame, clockwise) in a session co-organised by the SIF and Korea Foundation on cross-cultural lessons surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic. Along with him are (clockwise from first frame) Mr Lee Dae Joong, prof Kwon Soonman, Dr Leong Hoe Nam, and prof Eric Mobrand.

“Whether in remote islands in the Riau Archipelago or rural communities in Northern Laos, the first thing a public health professional needs to do is to understand the needs and beliefs of the population. And then, in a collaborative and respectful way, work with and within the belief systems to put forward public health strategies,” he notes.

Closer to home, these insights have helped to mitigate the outbreak in Singapore’s migrant workers’ dormitories.

“During Peacetime, Global Cooperation Establishes A Degree Of Trust And Mutual Understanding That Is Absolutely Crucial If Countries Are To Openly Share Resources, Data And Lessons For When Pandemics Occur.”

Professor Teo Yik Ying, Dean, SSHSPH

“TikTok shared with us that it has many Bangladeshi users in Singapore and we corroborated this with our own digital media analytics,” he shares.

This led the SSHSPH to work with media teams to produce over 80 public health videos to disseminate to migrant workers through social media platforms such as Facebook and TikTok.

Associate prof Jeremy Lim (in black) at a 2017 meet in South Africa where the team studied smart-phoneenabled hearing and vision screening programmes.

His team is also in the midst of embarking on a new cross-country collaboration with Bangladeshi colleagues to better understand the experiences of the Bangladeshi migrant workers in Singapore during this pandemic. Migrant workers will be asked to share how Covid-19 has affected them via an open-ended question, and SSHSPH will work with fellow academics in Bangladesh to analyse and interpret the answers. “This is a highly contextual type of research and hence the imperative for multinational teams,” he explains.

At the same time, SSPSPH is working with universities around the world – including Hong Kong University, Harvard University and Australian National University – to analyse the early responses to Covid-19 among different countries and identify predictors of success in subduing the first waves, as well as containing further spread. “We opened up the research teams to include students from all the different universities and hope that these interactions will help students learn about each other’s countries and systems, while paving the way for future collaborations at multiple levels,” he says.

“The World Is Only As Safe As The Least Prepared Country In A Pandemic. Cross-border Collaborations Will Need To Be Strengthened For The World To Be Better Prepared For The Next Pandemic.”

This may prove invaluable for both the current crisis and future pandemics. “The reality is that the current collaborative efforts towards global public health are still inadequate. Even the regional blocs in different parts of the world have been slow to come together to mount a collective response, be it in sharing resources, data or knowledge,” observes professor Teo Yik Ying, Dean of NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and an internationally recognised academician in the genome statistics field. “Most countries have executed unilateral responses to Covid-19, especially when it came to border closures. This is evident when migrant workers who cross borders daily in Europe, Asia, and the Americas suddenly found themselves jobless overnight when countries decided to impose border restrictions that limit entry and exit,” he explains. “These control measures also exacted a toll on supply chains which took weeks, if not months, to rectify. As seen during the start of the pandemic, there were shortages of crucial medical equipment and supplies in a few countries worst-hit by Covid-19, but disappointingly many of the regional blocs fail to come forward to address these shortages within their member states,” he adds with concern.

Indeed, international cooperation during a pandemic will enable advanced countries to assist resource-scarce nations to mount a robust response against an outbreak. But its importance even when there is no pandemic cannot be overstated.

“During peace-time, international cooperation establishes a degree of trust and mutual understanding between countries that is absolutely crucial if they are to openly share resources, data and lessons for when pandemics occur,” prof Teo explains. “The world is only as safe as the least prepared country in a pandemic. Cross-border collaborations will need to be strengthened for the world to be better prepared for the next pandemic.”