Stories > Setting New Goals

Setting New Goals

Singapore football legend Fandi Ahmad talks about how being exposed to other cultures can be a boon to one’s personal development and sporting ambitions.

PHOTOS BERITA HARIAN; THE STRAITS TIMES/SPH MEDIA

still remember the incident like it was yesterday. It was a rainy winter day. The pitch was slick. The ball was right there for the taking, but a high boot from the opponent sent me hurtling in another direction. There was a sharp pain, and then there was blood.

The coach seemed almost nonchalant about the injury. He gestured for me to see the doctor, who stopped the bleeding before slapping on a generous dollop of skin glue over the wound on my face. “Okay, get back out there, Fandi,” said the doctor.

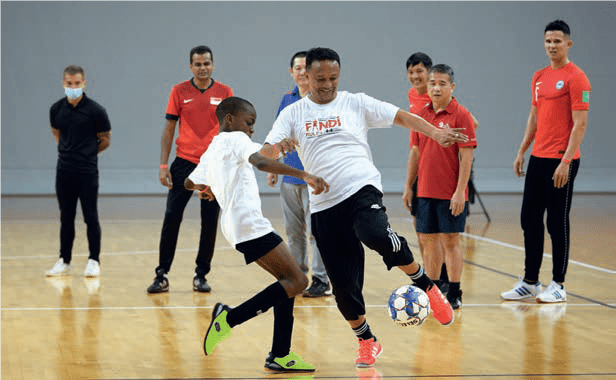

Fandi Ahmad and Titans U-10 player Aaron Emuejeraye, son of former Lion Precious Emuejeraye, playing in the inaugural Fandi Rules event – a competition launched by the footballer – as Minister for Culture, Community and Youth Edwin Tong (second from right) watches.

This was just a regular training session in the Netherlands, where no one fussed over the incident. Giving a hundred per cent and not batting an eyelid, even during training, was simply the way things worked in Dutch football.

But this hardly means that the Dutch are an unfeeling bunch. If anything, I found them to be happy-go-lucky. They train hard on the pitch, but they also play hard off it.

My teammates in FC Groningen would often hit the bars to celebrate with a few pints of beer after a victory, but they were always respectful about the fact that I, as a Muslim, could not drink alcohol. The mutual understanding of cultural differences helped to strengthen the team spirit.

SPORTS AND CULTURE

Many friendships were forged during the years that I spent in the Netherlands. I still keep in close contact with my former teammate Henk de Haan.

I do not think I would have become the footballer I was if not for my stint with FC Groningen. This experience made me tougher, both physically and mentally. More importantly, it also opened my eyes to the world and other cultures. When you live in another country and learn about a new culture, you gain new, valuable perspectives that inherently make you a more well-informed person.

When I was in the Netherlands, I made it a point to learn Dutch as most of my teammates did not speak much English. The Indonesian family I lived with made me read the newspapers and watch the news. I also took private tuitions. Within just three months, I was able to speak Dutch fluently and connect with my peers more effectively.

“I do not think I would have become the footballer I was if not for my stint with FC Groningen. When you live in another country and learn about a new culture, you gain new, valuable perspectives that inherently make you a more well-informed person.”

Fandi has represented Singapore more than 100 times in football matches, scoring 54 goals.

COMPETITIVE EXCELLENCE

Of course, football academies have emerged locally in recent years. But Singapore, at least for the time being, does not have the optimal environment for our youths to develop into world-class players. This was one of the reasons why I sent my sons – both footballers – Irfan and Ikhsan to Chile. I was convinced that having them be exposed to a higher level of training intensity and competition would be a boon to their development. Moreover, they could pass on what they had learnt from this stint to their Singaporean peers after they return.

Compared with other Asean nations, young Singaporean footballers spend significantly lesser time on the pitch training and playing matches. The local school tournament season lasts only around three months. On the other hand, young footballers in countries like Indonesia play throughout the year. As such, it is imperative that our youths get to play more.

Ironically, Singapore has struggled to catch up with its footballing rivals because the nation has developed rapidly. Today, most families lead a relatively comfortable life and need not worry about making ends meet or securing education for their kids. But in many footballing nations, the youths do not have this luxury of choice. For many of them, becoming a professional footballer is their ticket out of poverty. With so much at stake, the hunger to succeed is immeasurable, and this translates into a footballing environment that breeds excellence.

Fandi with his sons (from left) Ilhan, Irfan, Ikhsan and Iryan, all of whom are footballers.

Changes to Singapore’s physical environment over the decades have also created challenges. Earlier, it was easy to find an empty field to play football in. Urbanisation has turned many of these fields into property developments. While futsal courts have emerged in the heartlands, such spaces allow only a few people to play at a time. Some of these courts charge fees, presenting another barrier to entry.

There is also the issue of children being relatively less physically active than those from the older generations. During my childhood days, I was always out playing football. These days, you’d often find many children playing computer games at home. We must find ways to address these cultural changes.

One of the solutions is to change the environment we are in – as I mentioned earlier about gaining overseas exposure.

A BALANCING ACT

Many have argued that Singapore’s mandatory National Service (NS) for males is an impediment to the development of our local footballers and that the best players should be exempt from it. I disagree – because this experience is crucial to cultivating discipline and maturity in players.

Indeed, the years during which Singaporean men must serve NS are some of the most important in the developmental stage. But this does not mean we have to pick one over the other. A footballer can continue to train while fulfilling his NS obligations. That is where the Singapore Armed Forces Sports Association comes in. The organisation had, after all, previously produced SAFFC [later known as Warriors FC], one of the most formidable teams in the nation’s football league.

Another constant refrain is that we should bring in the best international coaches to elevate the level of the sport in Singapore. While these intentions are good, and Singapore has certainly gained from leveraging the expertise of foreign sports managers, the solution is not as straightforward.

Fandi (in checkered shirt) interacts with football fans at Istigfahar Mosque before the screening of the 2006 World Cup final match.

“The passion for sport itself is not defined by financial incentives and a competitive streak. It is, in fact, a natural binding agent.”

Foreign coaches can sometimes find adapting to the local context a huge challenge, because it is a stark contrast to what they are used to. Singapore’s football ecosystem, for instance, is still in its nascent stages, and many of the resources these coaches think should already exist… do not. I still remember how former national football coach Bernd Stange regaled at how modern and beautiful Singapore is, but was surprised by the comparative lack of development in our football scene.

That is not to say that we should rely solely on local coaches and technical staff – because the number of them who get to experience high-level football overseas is limited. I would like to see more support afforded to these individuals to hone their craft and gain first-hand experience in another country. Some of our athletes told me that they had to give up on their sporting aspirations because it was not financially viable.

I hope to see all aspects of society – from the government to the sporting bodies and corporate entities – coming together to back our local athletes and coaches. These partnerships could help invigorate the local sporting culture by boosting it financially and making it competitive.

The Singapore team that clinched the Malaysia League and Malaysia Cup double in 1994.

Having said that, the passion for sport itself is not defined by financial incentives and a competitive streak. It is, in fact, a natural binding agent in society. I have been to the World Cup competitions in Mexico and France and it was always heartening to see how the sport created togetherness despite the rivalries.

This is exactly the case in Singapore. I look back with fondness at the Malaysia Cup days when Singaporeans from all walks of life would gather at the National Stadium to cheer on the Lions. Perhaps few people today would know that the Malaysia Cup is Asia’s longest-running football tournament – it was founded in 1921 – and saw Malaysian state teams competing with Singapore and Brunei. The year 1994 was particularly special to me and fellow Singaporeans – we won the tournament after a 14-year hiatus. It also marked the last time I played in the tournament, as Singapore withdrew from the Malaysia Cup the following year.

This is why football is called The Beautiful Game – it brings people together and creates bonds that negate barriers such as race, language and religion.

ABOUT THE AUTHORSingaporean Fandi Ahmad is highly regarded as the most successful local footballer. He has played for clubs and leagues in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Netherlands. In 1983, he became the first Singaporean to play in a European league after being signed by Dutch First Division team FC Groningen. In 1999, Fandi was voted into Groningen’s Hall of Fame as one of the club’s 25 best players. He was awarded Singapore’s Public Service Medal in 1994. Fandi retired from the Singapore national team at the end of 1997. |